The Lying Stones of Marrakech (24 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

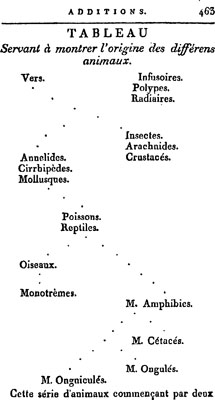

Finally, Lamarck explicitly connected the two reforms: the admission of two sequences of spontaneous generation at the bottom, and a branching among higher vertebrates at the top: “The animal scale begins with at least two branches; in the course of its extent, several branches seem to end in different places.”

After

Philosophic zoologique

of 1809, Lamarck wrote one additional major book on evolution, the introductory volume (1815) to his

Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres

. Here, he abandoned all the tentativeness of his 1809 revision, and announced his conversion to branching as the fundamental pattern of evolution. In direct contradiction to the linear model that had shaped all his previous work, Lamarck stated simply, and without ambiguity:

Dans sa production des differents animaux, la nature n'a pas executé une série unique et simple

.

[In its production of the different animals, nature has not fashioned a single and simple series.]

He then emphasized the branching form of his new model, and explained how the division of worms, inspired by Cuvier's observations, had broken his former system and impelled his revision:

Lamarck's first depiction of a branching model for the history of life. From the appendix to Philosophic zoologique (1809)

.

The order is far from being simple; it is branching

[rameux]

and even appears to be constructed of several distinct seriesâ¦. The animals that belonged to the class of worms display a great disparity of organizationâ¦. The most imperfect of these animals arise by spontaneous generation, and the worms [now restricted to

vers intestins

, with annelids removed] truly form their own series, later in origin than the one that began with infusorians.

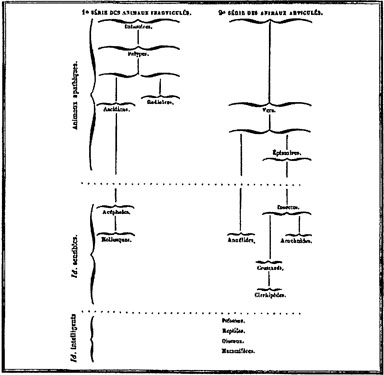

Lamarck's third and last chart (reproduced here from his 1815 volume) shows how far he had progressed both in his own confidence, and in copious branching on his new tree of life. He tides the chart “presumed order of the formation of animals, showing two separate and subbranching series.” Note how the two major lines of separate spontaneous generationâone beginning with infusorians, the other with internal wormsâare now clearly marked and separated. Note also how each of the series also divides within itself, thus

establishing the process of branching as a key theme at all scales of the system. The infusorian line branches at the level of polyps (corals and jellyfish) into a line of radiates and a line terminating in mollusks. The second line of worms also branches in two, leading to annelids on one side and insects on the other. But the insect Une then splits again (a tertiary division) into a lineage of crustaceans and barnacles (labeled

cirrhipèdes)

and another of arachnids (spiders and scorpions).

Finally, we must recognize that these major changes do not only affect the overt geometry of animal organization. The conversion from linearity to branching alsoâperhaps even more importandyâmarks a profound shift in Lamarck's underlying theory of nature. He had based his original system, defended explicidy and vociferously until 1809, on a fundamental division of two independent forcesâa primary cause that builds basic anatomies in an unbroken line of progress, and a subsidiary lateral force that draws single lineages off the line into byways of immediate adaptation to local environments. A set of philosophical consequences then spring from this model: the predictable and lawlike character of evolution lies patent in the primary force and its ladder of progress reaching to man, while accidents of history (leading to local adaptations) can then be dismissed as secondary and truly independent from the overarching order.

Lamarck's fully developed tree of lifefrom 1815

.

But the branching system destroys this neat and comforting scheme. First of all, the two forces become intermingled and conflated in the branching itself. We can no longer distinguish two independent and orthogonal powers working at right angles. Progress may occur along any branch to be sure, but the very act of division implies an environmental impetus to split the main lineâand Lamarck had always advocated a complete and principled distinction between a single and inexorable main line and the numerous minor deviations that can draw off a long-necked giraffe or an eyeless mole, but can never disrupt or ramify the major designs of animal life. In the new model, however, environment intrudes at the first construction of basic orderâas one group arises spontaneously in ponds, and another inside the bodies of other creatures! Moreover, each of the two resulting lines then branches further, and unpredictably, under environmental impetuses that were not supposed to derail the force of progress among major groupsâas when insects split into a terrestrial line of arachnids and a marine line leading to crustaceans and barnacles.

Second, the forces of history and natural complexity have now triumphed over the scientific ideal of a predictable and lawlike system. The taxonomy of animals could no longer embody an overarching plan of progress, illustrating the fundamental order, harmony, and predictable good sense of the natural world (perhaps even the explicit care of a loving deity, whose plans we may hope to understand because he thinks as we do). Now, the confusing, particular, local, and unpredictable forces of complex environments hold sway, ready at any time to impose a deviation upon any group with enough hubris to suppose that Emerson's forthcoming words could describe their inevitable progress:

And striving to be man, the worm

Mounts through all the spires of form

.

VI. L

AMARCK'S

E

PILOGUE AND

M

Y

O

WN

Following his last and greatest treatise on the anatomy of invertebrate organisms, Lamarck published only one other major workâ

Analytic System of Positive Knowledge About Man

(1820). This rare book has not been consulted by previous historians who traced the development of Lamarck's changing views on the classification of animals. Thus, traditional accounts stop at Lamarck's 1815 revision, with its fundamental distinction between two separate lineages of spontaneous generation. The impression therefore persists that Lamarck never fully embraced the branching model, later exemplified by Darwin as the “tree

of lifeӉwith a common trunk of origin for all creatures and no main line of growth thereafter. Lamarck had compromised his original ladder of progress by advocating two separate origins, but he could continue to stress linearity in each of the resulting series.

But his 1820 book, although primarily a treatise on psychology, does include a chapter on the classification of animalsâand I discovered, in reading these pages, that Lamarck did pursue his revisionary path further, and did finally arrive at a truly branching model for a tree of life. Moreover, in a remarkable passage, Lamarck also recognizes the philosophical implications of his full switch by acknowledging a reversal in his ranking of natural forces in one of the most interesting (and honorable) intellectual conversions that I have ever read.

Lamarck still talks about forces of progress and forces of branching, and he does argue that progress will proceed along each branch. But branching has triumphed as a primary and controlling theme, and Lamarck now frames his entire discussion of animal taxonomy by emphasizing successive points of division. For example, consider this epitome of vertebrate evolution:

Reptiles come necessarily after fishes. They build a branching sequence, with one branch leading from turdes to platypuses to the diverse group of birds, while the other seems to direct itself, via lizards, toward the mammals. The birds then ⦠build a richly varied branching series, with one branch ending in birds of prey.

(In previous models, Lamarck had viewed birds of prey as the top rung of a single avian ladder.)

But much more radically, his 1815 model based on two lines of spontaneous generation has now disappeared. In its place, Lamarck advocates the same tree of life that would later become conventional through the influence of Darwin and other early evolutionists. Lamarck now proposes a single common ancestor for all animals, called a monad. From this beginning, infusorians evolve, followed by polyps, arising “direcdy and almost without a gap.” But polyps then branch to build the rest of life's tree: “instead of continuing as a single series, the polyps appear to divide themselves into three branches”âthe radiates, which end without evolving any further; the worms, which continue to branch into all phyla of segmented animals, including annelids, insects, arachnids, crustaceans, and barnacles, each by a separate event of division; and the tunicates (now regarded as marine organisms closely related to vertebrates), which later split to form several Unes of mollusks and vertebrates.

Lamarck then acknowledges the profound philosophical revision implied by a branching model for nature's fundamental order. He had always viewed the linear force of progress as primary. As late as 1815, even after he had changed his model to permit extensive branching and two environmentally induced sequences of spontaneous generation, Lamarck continued to emphasize the primary power of the linear force, compared with disturbing and anomalous exceptions produced by lateral environmental causes, called

l'infiuence des cir-constances

. To restate the key passage quoted earlier in this essay:

The plan followed by nature in producing animals clearly comprises a predominant prime cause. This endows animal life with the power to make organization gradually more complexâ¦. Occasionally a foreign, accidental, and therefore variable cause has interfered with the execution of the plan ⦠[producing] branches that depart from the series in several points and alter its simplicity.

But Lamarck, five years later in his final book of 1820, now abandons this controlling concept of his career, and embraces the opposite conclusion. The influence of circumstances (leading to a branching model of animal taxonomy) rules the paths of evolution. All general laws, of progress or anything else, must be regarded as subservient to the immediate singularities of environments and histories. The influence of circumstances has risen from a disturbing and peripheral joker to the true lord of all (with an empire to boot):

Let us consider the most influential cause for everything done by nature, the only cause that can lead to an understanding of everything that nature producesâ¦. This is, in effect, a cause whose power is absolute, superior even to nature, since it regulates all nature's acts, a cause whose empire embraces all parts of nature's domainâ¦. This cause resides in the power that circumstances have to modify all operations of nature, to force nature to change continually the laws that she would have followed without [the intervention of] these circumstances, and to determine the character of each of her products. The extreme diversity of nature's productions must also be attributed to this cause.

Lamarck's great intellectual journey began with a public address about evolution, delivered in 1800 during a month that the revolutionary government

had auspiciously named

Floréal

, or flowering. He then developed the first comprehensive theory of evolution in modern scienceâan achievement that won him a secure place in any scientific hall of fame or list of immortalsâdespite the vicissitudes of his reputation during his own lifetime and immediately thereafter.

But Lamarck's original system failedâand not for the reasons that we usually specify today in false hindsight (the triumph of Mendelism over Lamarck's erroneous belief in inheritance of acquired characters), but by inconsistencies that new information imposed upon the central logic of Lamarck's system during his own lifetime. We can identify a fulcrum, a key moment, in the unraveling of Lamarck's original theoryâwhen he attended a lecture by Cuvier on the anatomy of annelids, and recognized that he would have to split his taxonomie class of worms into two distinct groups. This recognitionâwhich Lamarck recorded with excitement (and original art) as a handwritten insertion into his first published book on evolutionâunleashed a growing cascade of consequences that, by Lamarck's last book of 1820, had destroyed his original theory of primary ladders of progress versus subsidiary lateral deviations, and led him to embrace the opposite model (in both geometry of animal classification, and basic philosophy of nature) of a branching tree of life.