The Lying Stones of Marrakech (32 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Scattered observations of dinosaur bones, usually misinterpreted as human giants, pervade the earlier history of paleontology, but the first recognition of giant terrestrial reptiles from a distant age before mammalian dominance (the marine ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs had been defined a few years earlier) did not long predate Owen's christening. In 1824, the Reverend William Buckland, an Anglican divine by tide, but a leading geologist by weight of daily practice and expertise, named the first genus that Owen would eventually incorporate as a dinosaurâthe carnivorous

Megalosaurus

.

Buckland devoted his professional life to promoting paleontology and religion with equal zeal. He became the first officially appointed geologist at Oxford University, and presented his inaugural lecture in 1819 under the title “Vindiciae geologicae; or the connexion of geology with religion explained.” Later, in 1836, he wrote one of the eight Bridgewater Treatises, a series generously endowed by the earl of Bridgewater upon his death in 1829, and dedicated to proving “the power, wisdom and goodness of God as manifested in the creation.” Darwin's circle referred to this series as the “bilgewater” treatises, and the books did represent a last serious gasp for the venerable, but fading, doctrine of “natural theology” based on the so-called “argument from design”âthe proposition that God's existence, and his attributes of benevolence and perfection, could both be inferred from the good design of material objects and the harmonious interaction among nature's parts (read, in biological terms, as the excellent adaptations of organisms, and the harmony of ecosystems expressed as a “balance of nature”).

Buckland (1784-1856) provided crucial patronage for several key episodes in Owen's advance, and Owen, as a consummate diplomat and astute academic politician, certainly knew and honored the sources of his favors. When Owen named dinosaurs in 1842, the theoretical views of the two men could only evoke one's favorite metaphor for indistinction, from peas in a pod, to Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Owen later became an evolutionist, though never a supporter of Darwinian natural selection. One might be cynical, and correlate Owen's philosophical shift with the death of Buckland and other powerful men of the old guard, but Owen was too intelligent (and at least sufficiendy honorable) to permit such a simple interpretation, and his later evolutionary views show considerable subtlety and originality. Nonethelessâin a point crucial to this essayâOwen remained an unreconstructed Bucklandian creationist, committed to the functionalist approach of the argument from design, when he christened dinosaurs in 1842.

Gideon Mantell, a British surgeon from Sussex, and one of Europe's most skilled and powerful amateur naturalists, named a second genus (that Owen

would later include among the dinosaurs) in 1825âthe herbivorous

Iguanodon

,now classified as a duckbill. Later, in 1833, Mantell also named

Hylaeosaurus

, now viewed as an armored herbivorous dinosaur ranked among the ankylosaurs.

Owen united these three genera to initiate his order Dinosauria in 1842. But why link such disparate creaturesâa carnivore with two herbivores, one now viewed as a tall, upright, bipedal duckbill, the other as a low, squat, four-footed, armored ankylosaur? In part, Owen didn't appreciate the extent of the differences (though we continue to regard dinosaurs as a discrete evolutionary group, thus confirming Owen's basic conclusion). For example, he didn't recognize the bipedality of some dinosaurs, and therefore reconstructed all three genera as four-footed creatures.

Owen presented three basic reasons for proposing his new group. First, the three genera share the most obvious feature that has always set our primal fascination with dinosaurs: gigantic size. But Owen knew perfecdy well that similarity in bulk denotes little or nothing about taxonomie affinity. Several marine reptiles of the same age were just as big, or even bigger, but Owen did not include them among dinosaurs (and neither do we today).

Moreover, Owen's anatomical analysis had greatly reduced the size estimates for dinosaurs (though these creatures remained impressively large). Mantell had estimated up to one hundred feet in length for

Iguanodon

,a figure reduced to twenty-eight feet by Owen. In the 1844 edition of his

Medals of Creation

(only two years after Owen's shortening, thus illustrating the intensity of public interest in the subject), Mantell capitulated and excused himself for his former overestimate in the maximally exculpatory passive voice:

In my earliest notices of the

Iguanodon

⦠an attempt was made to estimate the probable magnitude of the original by instituting a comparison between the fossil bones and those of the Iguana.

But the modern iguana grows short legs, splayed out to the side, and a long tail. The unrelated dinosaur

Iguanodon

had very long legs by comparison (for we now recognize the creature as bipedal), and a relatively shorter tail. Thus, when Mantell originally estimated the length of

Iguanodon

from very incomplete material consisting mostly of leg bones and teeth, he erred by assuming the same proportions of legs to body as in modern iguanas, and by then appending an unknown tail of greatly extended length.

Second, and most importantly, Owen recognized that all three genera share a set of distinct characters found in no other fossil reptiles. He cited many technical

details, but focused on the fusion of several sacral vertebrae to form an unusually strong pelvisâan excellent adaptation for terrestrial life, and a feature long known in

Megalosaurus

,but then only recently affirmed for

Iguanodon

,thus suggesting affinity. Owen's first defining sentence in his section on dinosaurs (pages 102-3 of his 1842 report) emphasizes this shared feature:“This group, which includes at least three well-established genera of Saurians,is characterized by a large sacrum composed of five anchylosed [fused] vertebrae of unusual construction.”

Third, Owen noted, based on admittedly limited evidence, that dinosaurs might constitute a complete terrestrial community in themselves, not just a few oddball creatures living in ecological corners or backwaters. The three known genera included a fierce carnivore, an agile herbivore, and a stocky armored herbivoreâsurely a maximal spread of diversity and ecological range for so small a sample. Perhaps the Mesozoic world had been an Age of Dinosaurs (or rather, a more inclusive Age of Reptiles, with dinosaurs on land, pterodactyls in the air, and ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs in the sea). In this view, dinosaurs became the terrestrial component of a coherent former world dominated by reptiles.

Owen then united all his arguments to characterize dinosaurs in a particularly flattering way that justified his etymological choice of “fearfully great.” In short, Owen depicted dinosaurs not as primitive and anatomically incompetent denizens of an antediluvian world, but rather as uniquely sleek, powerful, and well-designed creaturesâmean and lean fighting and eating machines for a distinctive and distinguished former world. Owen emphasized this central point with a striking rhetorical device, guaranteed to attract notice and controversy: he compared the design and efficiency of dinosaurs with modern (read superior) mammals, not with slithery and inferior reptiles of either past or present worlds.

Owen first mentioned this argument right up front, at the end of his opening paragraph (quoted earlier in this essay) on the definition of dinosaurs:

The bones of the extremities are of large proportional size, for Sauriansâ¦. [They] more or less resemble those of the heavy pachydermal Mammals, and attest⦠the terrestrial habits of the species.

Owen then pursues this theme of structural and functional (not genealogical) similarity with advanced mammals throughout his reportâas, for example, when he reduces Mantell's estimate of dinosaurian body size by comparing their

leg bones with the strong limbs of mammals, attached under the body for maximal efficiency in locomotion, and not with the weaker limbs of reptiles, splayed out to the side and imposing a more awkward and waddling gait. Owen writes:

The same observations on the general form and proportions of the animal

[Iguanodon]

and its approximation in this respect to the Mammalia, especially to the great extinct Megatherioid [giant ground sloth] or Pachydermal [elephant] species, apply as well to the

Iguanodon

as to the

Megalosaurus

.

Owen stresses this comparison again in the concluding paragraphs of his report (and for a definite theoretical purpose embodying the theme of this essay). Here Owen speaks of “the Dinosaurian order, where we know that the Reptilian type of structure made the nearest approach to Mammals.” In a final footnote (and the very last words of his publication), Owen even speculatesâ thus anticipating an unresolved modern debate of great intensityâthat the efficient physiology of dinosaurs invites closer comparison with warm-blooded mammals than with conventional cold-blooded modern reptiles:

The Dinosaurs, having the same thoracic structure as the Crocodiles, may be concluded to have possessed a four-chambered heart; and,from their superior adaptation to terrestrial life, to have enjoyed the function of such a highly-organized center of circulation in a degree more nearly approaching that which now characterizes the warm-blooded Vertebrata.

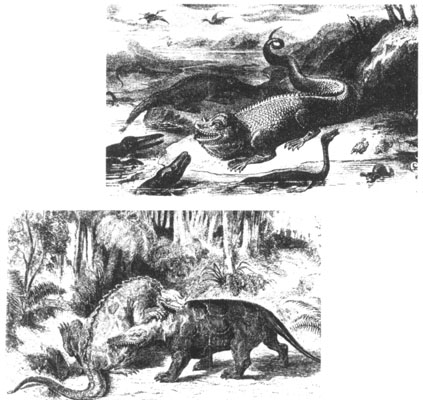

When we contrast artistic reconstructions made before and after Owen's report, we immediately recognize the dramatic promotion of dinosaurs from ungainly, torpid, primeval reptilian beasts to efficient and well-adapted creatures more comparable with modern mammals. We may gauge this change by comparing reconstructions of

Iguanodon

and

Megalosaurus

before and after Owen's report. George Richardson's

Iguanodon

of 1838 depicts a squat, elongated creature, presumably relegated to a dragging, waddling gait while moving on short legs splayed out to the side (thus recalling God's curse upon the serpent after a portentous encounter with Eve:“upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life”). But Owen, while wrongly interpreting all dinosaurs as four-footed, reconstructed them as competent and efficient runners, with legs held under the body in mammalian fashion. Just compare

Richardson's torpid dinosaur of 1838 with an 1867 scene of

Megalosaurus

fighting with

Iguanodon

, as published in the decade's greatest work in popular science, Louis Figuier's

The World Before the Deluge

.

Owen also enjoyed a prime opportunity for embodying his ideas in (literally) concrete form, for he supervised Waterhouse Hawkins's construction of the first full-sized, three-dimensional dinosaur modelsâbuilt to adorn the reopening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham in the early 1850s. (The great exhibition hall burned long ago, but Hawkins's dinosaurs, recently repainted, may still be seen in all their gloryâless than an hour's train ride from central London.) In a famous incident in the history of paleontology, Owen hosted a New Year's Eve dinner on December 31, 1853,

within

the partially completed

model of

Iguanodon

. Owen sat at the head of the table, located within the head of the beast; eleven colleagues won coveted places with Owen inside the model, while another ten guests (the Victorian version of a B-list, I suppose) occupied an adjoining side table placed outside the charmed interior.

An 1838 (top) compared with an 1867 (bottom) reconstruction of dinosaurs, to show the spread of Owen's view of dinosaurs as agile and active

.

I do not doubt that Owen believed his favorable interpretation of dinosaurs with all his heart, and that he regarded his conclusions as the best reading of available evidence. (Indeed, modern understanding places his arguments for dinosaurian complexity and competence in a quite favorable light.) But scientific conclusionsâparticularly when they involve complex inferences about general worldviews, rather than simple records of overtly visible factsâalways rest upon motivations far more intricate and tangled than the dictates of rigorous logic and accurate observation. We must also pose social and political questions if we wish to understand why Owen chose to name dinosaurs as fearfully great: who were his enemies, and what views did he regard as harmful, or even dangerous, in a larger than purely scientific sense?

When we expand our inquiry in these directions, the ironic answer that motivated this essay rises to prominence as the organizing theme of Owen's deeper motivations: he delighted in the efficiency and complexity of dinosaursâand chose to embody these conclusions in a majestic nameâbecause dinosaurian competence provided Owen with a crucial argument against the major evolutionary theory of his day, a doctrine that he then opposed with all the zeal of his scientific principles, his conservative political beliefs, and his excellent nose for practical pathways of professional advance.

I am not speaking here of the evolutionary account that would later bear the name of Darwinism (and would prove quite compatible with Owen's observations about dinosaurs)âbut rather of a distinctively different and earlier version of “transmutation” (the term then generally used to denote theories of genealogical descent), best described as the doctrine of “progressionism.” The evolutionary progressionists of the 1840s, rooting their beliefs in a pseudo-Lamarckian notion of inherent organic striving for perfection, looked upon the fossil record as a tale of uninterrupted progress within each continuous lineage of organisms. Owen, on the contrary, viewed the complexity of dinosaurs as a smoking gun for annihilating such a sinister and simplistic view.