The Magician's Elephant (6 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

“One moment,” said Peter. He disappeared from the window and came back again, his hat firmly upon his head.

“And now, then, you are officially attired and ready to receive the happy news of which I, Leo Matienne, am the proud bearer.” Leo cleared his throat. “I am pleased to let you know that the magician’s elephant will be on display for the edification and illumination of the masses.”

“But what does that mean?” said Peter.

“It means that you may see the elephant on the first Saturday of the month; that is, you may see her this Saturday, Peter, this Saturday.”

“Oh,” said Peter, “I will see her. I will find her!” His face suddenly became bright, so bright that Leo Matienne, even though he knew it was foolish, turned and checked to see if the sun had somehow performed the impossible and come out from behind a cloud to shine directly on Peter’s small face.

There was, of course, no sun.

“Close the window,” came the old soldier’s voice from inside the attic. “It is winter, and it is cold.”

“Thank you,” said Peter to Leo Matienne. “Thank you.” And he pulled the window shut.

In the apartment of Leo and Gloria Matienne, Leo sat down in front of the fire and heaved a great sigh and took off his boots.

“Phew,” said his wife. “Hand me your socks immediately.”

Leo removed his socks. Gloria Matienne took them from him and put them directly into a bucket filled with soapy water. “Without me,” she said, “you would have no friends at all, because no one would be able to bear the smell of your feet.”

“I do not want to surprise you,” said Leo, “but, as a matter of course, I keep my boots on in public places and there is no need then for anyone to smell my socks or my feet.”

Gloria came up behind Leo and put her hands on his shoulders. She bent and kissed the top of his head. “What are you thinking?” she said.

“I am imagining Peter,” said Leo Matienne, “and how happy he was to learn that he could see the elephant for himself. His face lit up in a way that I have never seen.”

“It is wrong about that boy,” said Gloria. She sighed. “He is kept a prisoner up there by that man, whatever he is called.”

“He is called Lutz,” said Leo. “His name is Vilna Lutz.”

“All day it is nothing but drilling and marching and more marching. I hear them, you know. It is a terrible sound, terrible.”

Leo Matienne shook his head. “It is a terrible thing altogether. He is a gentle boy and not really cut out for soldiering, I do not think. There is a lot of love in him, a lot of love in his heart.”

“Most certainly there is,” said Gloria.

“And he is up there with no one and nothing to love. It is a bad thing to have love and nowhere to put it.” Leo Matienne sighed. He bent his head back and looked up into his wife’s face and smiled. “And we are all alone down here.”

“Don’t say it,” said Gloria Matienne.

“It is only that—”

“No,” said Gloria. “No.” She put a finger to Leo’s lips. “We have tried and failed. God does not intend for us to have children.”

“Who are we to say what God intends?” said Leo Matienne. He was silent for a long moment. “What if?”

“Don’t you dare,” said Gloria. “My heart has been broken too many times, and it cannot bear to hear your foolish questions.”

But Leo Matienne would not be silenced. “What if?” he whispered to his wife.

“No,” said Gloria.

“Why not?”

“No.”

“Could it be?”

“No,” said Gloria Matienne, “it cannot be.”

A

t the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, in the cavernous dorm room, in her small bed, Adele was dreaming again of the elephant knocking and knocking, but this time Sister Marie was not at her post, and no one at all came to open the door.

Adele awoke and lay quietly and told herself that it was just a dream, only a dream. But every time she closed her eyes, she saw again the elephant, knocking, knocking, knocking, and no one at all answering her knock. And so she threw back the blanket and got out of bed and went down the stairs in the cold and the dark and made her way to the front door. She was relieved to see that there, just as always, just as for ever, sat Sister Marie in her chair, her head bent so far forward that it rested almost on her stomach, her shoulders rising and falling, and a small sound, something very much like a snore, issuing forth from her mouth.

“Sister Marie,” said Adele. She put her hand on the nun’s shoulder.

Sister Marie jumped. “But the door is unlocked!” she shouted. “The door is forever unlocked. You must simply knock!”

“I am inside already,” said Adele.

“Oh,” said Sister Marie, “so you are. So you are. It is you. Adele. How wonderful. Although of course you should not be here. It is the middle of the night. You should be in your bed.”

“I dreamed,” said Adele.

“But how lovely,” said Sister Marie. “And what did you dream of?”

“The elephant.”

“Oh, elephant dreams, yes. I find elephant dreams particularly moving,” said Sister Marie, “and portentous, yes, although I am forced to admit that I myself have yet to dream of an elephant. But I wait and hope. One must wait and hope.”

“The elephant came here and knocked, and there was no one to answer the door,” said Adele.

“But that cannot be,” said Sister Marie. “I am always here.”

“And then, another night, I dreamed that you opened the door and the elephant was there, and she asked for me and you would not let her in.”

“Nonsense,” said Sister Marie. “I turn no one away.”

“You said you could not understand her.”

“I understand how to open a door,” said Sister Marie gently. “I did it for you.”

Adele sat down on the floor next to Sister Marie’s chair. She pulled her knees up to her chest. “What was I like then?” she said. “When I first came here to you.”

“Oh, so small, like a mote of dust. You were only a few hours old. You had just been born, you see.”

“Were you glad?” said Adele. “Were you glad that I came?” She knew the answer. But she asked anyway.

“I will tell you,” said Sister Marie, “that before you arrived, I was sitting here in this chair, alone, and the world was dark, very dark. And then suddenly you were in my arms, and I looked down at you…”

“And you said my name,” said Adele.

“Yes, I spoke your name.”

“And how did you know it? How did you know my name?”

“The midwife said that your mother, before she died, had insisted that you be called Adele. I knew your name, and I spoke it to you.”

“And I smiled,” said Adele.

“Yes,” said Sister Marie. “And suddenly it seemed that there was light everywhere. The world was filled with light.”

Sister Marie’s words settled down over Adele like a warm and familiar blanket, and she closed her eyes. “Do you think,” she said, “that elephants have names?”

“Oh, yes,” said Sister Marie. “All of God’s creatures have names, every last one of them. Of that I am sure; of that I have no doubt at all.”

Sister Marie was right, of course: everyone has a name.

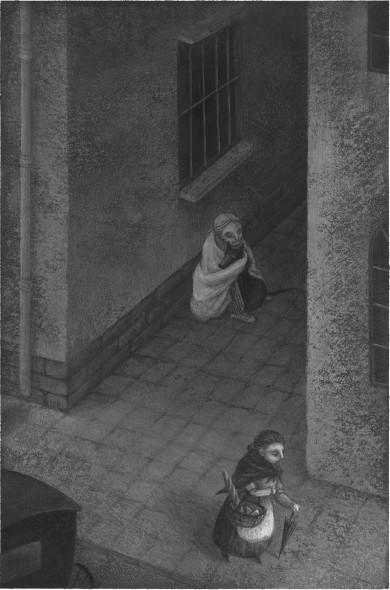

Beggars have names.

Outside the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, in a narrow alley off a narrow street, sat a beggar named Tomas; huddled up close to him, in an effort both to give and to receive warmth, was a large black dog.

If Tomas had ever had a last name, he did not know it. If he had ever had a mother or a father, he did not know that either.

He knew only that he was a beggar.

He knew how to stretch out his hand and ask.

Also he knew, without knowing how he knew, how to sing.

He knew how to construct a song out of the nothing of day-to-day life and how to sing that nothing into a song so beautiful that it could sustain the vision of a whole and better world.

The dog’s name was Iddo.

And there was a time when he had worked carrying messages and letters and plans across battlefields, transferring information from one officer of Her Majesty’s army to another.

And then one day, on a battlefield near Modegnel, as the dog weaved his way through the horses and soldiers and tents, he was caught by the blast from a cannon and was thrown high into the air and landed on his head in such a way that he was instantly, permanently blinded.

His one thought as he descended into darkness was, But who will deliver the messages?

Now when he slept, Iddo was forever running, carrying a letter, a map, battle plans, some piece of paper that would win the war, if only he could arrive with it in time.

The dog longed with the whole of his being to perform again the task that he had been born and bred to do.

Iddo wanted to deliver, just once more, a message of great importance.

In the cold and dark of the alley Iddo whimpered, and Tomas put his hand on the dog’s head and kept it there.

“Shh,” sang Tomas. “Sleep, Iddo. Darkness falls, but a boy wants to see the elephant; and he will. And this – this – is wonderful news.”

Beyond the alley, past the public parks and the police station, up a steep and tree-lined hill, stood the home of the Count and Countess Quintet, and in that mansion, in the darkened ballroom, stood the elephant.

She should have been sleeping, but she was awake.

The elephant was saying her name to herself.

It was not a name that would have made any sense to humans. It was an elephant name – a name that her brothers and sisters knew her by, a name that they spoke in laughter and in play. It was the name that her mother had given to her and that she had spoken often and with love.

Deep within herself, the elephant said this name, her name, over and over again.

She was working to remind herself of who she was. She was working to remember that somewhere, in another place entirely, she was known and loved.

V

ilna Lutz’s fever receded, and his words began again to make a dull and unremarkable and decidedly military sense. He had risen from his bed and trimmed his beard to a fine point and was seated on the floor. He was placing a collection of lead soldiers in the pattern of a famous battle.

“As you can see, Private Duchene, this was a particularly brilliant strategy on the part of General Von Flickenhamenger, and he executed it with a great deal of grace and bravery, bringing these soldiers from here to here, thereby performing a flanking manoeuvre that was entirely unexpected and exceedingly elegant and devastating. One cannot help but admire the genius of it. Do you admire it, Private Duchene?”