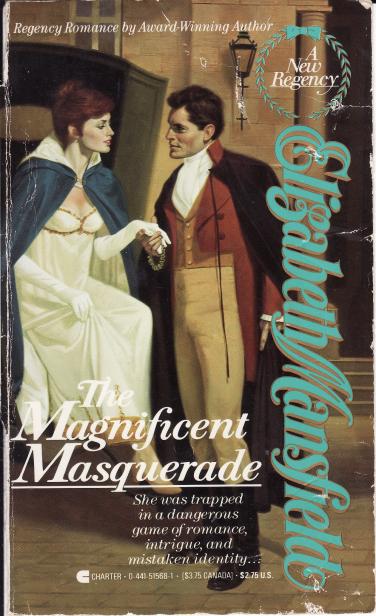

The Magnificent Masquerade

Read The Magnificent Masquerade Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mansfield

Prologue

One day, without any apparent provocation, Lord

Birkinshaw decided to marry off his daughter. This decision was astonishing,

for the girl hadn't reached her eighteenth birthday and was not yet

"out." However, the idea did not, as his wife later accused, come to

him "out of the clear blue sky"-in fact, he'd retorted, the sky

hadn't shown a scintilla of blue that whole dank day-but was the result of the

confluence of several minor incidents which seemed to him to lead inexorably to

that rather major decision. "And if you want the truth," he told his

wife roundly, in strong defense of a position which, no matter how

insupportable, would not be changed once he'd taken it, "that row we had

this morning might well have been the incident that touched off the entire

matter."

This was not quite the truth. Although the

argument with his wife had been somewhere in the back of his mind, the incident

that triggered his astounding decision had occurred later that afternoon, at

his club. It started with, of all things, the loud, clear ejaculation of a

curse. Someone had shouted "Oh, damnation!" and the sound had

reverberated shockingly throughout the club's high-ceilinged rooms. It was not

that the words themselves were shocking (for many more-salacious epithets had

been uttered thousands of times over the gaming tables), but that the rooms had

been so remarkably still a moment before.

Afternoons were always rather quiet at the

gentlemen's clubs on

Street

play at any hour of the day or night, their numbers were few in the afternoons,

most gentlemen reserving themselves for the headier excitement that filled the

gaming rooms during the evening hours. In the afternoons, there were often more

gentlemen dozing in easy chairs in the clubs' lounges than could be found at

the gaming tables.

This was certainly true that rainy January

afternoon at White's, the formidably fashionable club at Number 37. The famous

bow windows (which Raggett, the proprietor, had installed five years before, in

1811, and in which the Dandies of London so frequently exhibited themselves

while they eyed the female strollers on the street below) were on this day

completely deserted. The dining rooms were also empty, and only one table was

in use in the gaming rooms. So unpleasant was the weather that only a handful

of gentlemen could be found snoozing in the lounges. One of these was Thomas

Jessup, Viscount Birkinshaw. He'd folded his hands over his protuberant

stomach, stretched his legs out before him, covered his face with a

handkerchief to indicate to anyone who wished to converse with him that he was

not to be disturbed, and had gone to sleep.

If one is to understand fully the progression

of events, one must realize that Lord Birkinshaw was not compelled to venture

out in the rain to nap at his club; he had a perfectly satisfactory town house

in

satisfactory sitting room which in turn contained a perfectly satisfactory

armchair in which he could quite comfortably snooze. But his town house also

contained his wife, and it was to escape her carping that he'd taken himself

out in the rain and made his way to his club.

On this day the subject of his wife's diatribe

had been their daughter. The chit was in her fourth year at Miss Marchmont's

Academy for Young Ladies and evidently causing as much commotion there as she

had when she'd been living at home. Just the other day, he'd received a bill

from Berry Brothers for a half case of French wine and several dozen pastries

which had been delivered to the school. His wife, puzzled by the bill, had sent

a letter of inquiry to the headmistress of the school, a horsey-faced female

named Marchmont. The reply had come this morning. His daughter, it seemed, was

the culprit who'd ordered the wine and the sweets. The minx had managed to

smuggle them into the school in a laundry basket! Then she and her cronies had

held a midnight party up in the school's attic and had become quite boisterous.

They were, of course, promptly discovered, but by that time they were all

tipsy, and even as they were led off to bed they could not be prevented from

singing bawdy songs at the tops of their voices.

However, in her letter, the headmistress had

assured the parents that they had no cause to upset themselves over the

incident. The matter was not of any serious concern. They should not, she

warned, make too much of it, such as deluding themselves that the incident

signified in their daughter an incipient addiction to alcohol. There was

nothing more significant in the incident than an outbreak of youthful high

spirits.

The girls had been appropriately reprimanded,

their daughter in particular, and she'd accepted her punishment in a spirit of

good sportsmanship. The letter concluded with the statement that their

daughter's tendency to youthful prankishness did not in any way keep her from

ranking above average in her scholastic standing.

As far as Lord Birkinshaw was concerned, that

should have been that. The end of the story. To him, the matter was nothing

more than a rather good joke. But his wife did not agree. She'd spent the

morning nagging at him about it. "The girl has to be taken in hand,"

she insisted. "Youthful prankishness, indeed! She's almost eighteen. It's

time for her to put by that sort of nonsense! Do you know what will happen when

word gets out that Kitty is the sort of creature who tempts her friends to

drink and carouse? No bachelor worth a fig will come near her! Do you want your

daughter to end her days a dotty old maid?"

But Lord Birkinshaw didn't see what he could do

about it. What did his wife expect of him? Did she want him to take a whip to

the girl? After more than an hour of such haranguing, he did what any man of

sense would do-he banged out of the house.

His wife, he told himself as he walked to his

club through an icy rain, had an uncanny knack of cutting up his peace. The

disturbing feelings she'd generated remained with him all through his walk and

even after his arrival at White's. It took him several minutes to unwind before

he was able to sleep. And even then he found no peace-his dreams, too, were

affected. He found himself immersed in a nightmare in which he was hosting an

enormous wedding feast at which the guests were gorging on unbelievably huge

quantities of

Brothers' pastry and the most expensive French

champagne, his wife was glaring at him from the far end of a table a half-mile

long, his daughter (the bride) was swinging drunkenly from the chandelier, and,

worst of all, he himself, having forgotten to put on his britches, was parading

around the room in his smalls. It was then that he heard someone say, quite

loudly and from very close by, "Oh, damnation!" He sat up with a

start. That voice had certainly not emanated from his dream. He pulled the

handkerchief from his face and found himself staring at Lord Edgerton, seated

just opposite him. "What's that?" he asked, the last vestiges of his

dream dissipating into the air. "Did you say something, Greg?"

Gregory William Wishart, Earl of Edgerton, was

another regular member of White's easy-chair set, although he was much younger

than most of them. Only five-and-thirty, Edgerton was the head of a household

even more troublesome than Birkinshaw's. With a dithery mother, a brother who

was always getting into scrapes, and a sister who was convinced she teetered on

the brink of serious illness, Edgerton, too, used the club to escape the

tensions of his household, at least whenever he came to town from his Suffolk

estate. At this moment, he was holding a letter clutched in his right hand,

while his left supported his forehead, the fingers buried in a mass of dark,

gray-streaked hair. "I'm sorry for waking you, Birkinshaw," he

apologized. "It's just this deuced message I've received from

been sent down again."

"You don't mean it! What's the boy done

this time?"

"They don't say. But it must have been

deplorable. The last time Toby was sent down, he'd been found running a

gambling den in a room right behind the chapel! This must have been worse, for

this message informs me that it's for good this time. I'm afraid the Honorable

Tobias Wishart's muffed his last chance. Dash it all, I'd like to give my

deuced brother a good thrashing!"

"I know how you feel, old fellow. My wife

was saying the same thing about our daughter. Practically suggested I take a

whip to the girl."

"Oh?"

"Yes, a whip! What a wild, trouble-making

minx she is, to be sure. Seems the chit bought champagne, had it smuggled into

the school somehow, and then she and her cronies all got drunk as lords."

"Good God! Did they send her down,

too?"

"No, they didn't, for which I thank my

lucky stars. Don't know what life'd be like if she were sent home. We'd

scarcely pass a day without a crisis. Last time our Kitty was home the to-do

she stirred up was unbelievable. First she made eyes at one of the footmen, who

promptly lost his head over her and had to be sacked. Then she ran up a bill at

Hoby's for nine nine, mind you!-pairs of boots. Then she decided she wanted to

prepare a Charlotte Americaine with her own hands and caused such a stir in the

kitchen that we almost lost our cook. And, finally, she borrowed her mother's

emerald brooch and then sold it to a cent-per-cent and gave the money to help a

friend elope to Scotland, which brought the friend's parents to our house in

such a state that I feared they would commit murder-and all this, mind you, in

a mere three days' time!"

Lord Edgerton grinned, although he shook his

head in sympathy. "Amazing, isn't it, the mischief youngsters can concoct

these days? I sometimes feel, when I compare myself with my brother, that I and

my generation must have lacked imagination. I don't think we were capable of

concocting such scrapes. Toby, when he was home for his school holiday, ran up

a bill at Tattersall's for over a thousand pounds, made some poor young lady

fall into hysterics at the dinner table by telling her that the wine she'd just

drunk was really a love potion, and scandalized Lady Jersey by appearing at

Almack's in his riding clothes. And, I may add, that's the week he believed

himself to have been a model of good behavior!"

Birkinshaw snorted. "Young scamp! He needs

to be legshackled, that's what he needs. Once a fellow's leg-shackled, you know,

he's less likely to carry on. Responsibilities, you know. Marital duties.

Having to please someone besides himself. Having someone who'll call him to

account-who'll demand to know where he spent his time or his money. Having

someone who'll expect him to show his face at dinner and all that. You ought to

find him someone, Greg. Someone who . good God! Oh, I say! Greg, my boy, I

think I'm about to give birth to a splendid idea! A really splendid idea!"

"Are you indeed?" Lord Edgerton

laughed. "And what idea is that?"

"Marry your brother to my daughter! It'd

be the answer for both of them. Each one has enough spirit to tame the

other!"

"Come now, Birkinshaw, you can't be

serious. Your daughter's just a child! A mere schoolgirl, isn't she?"

"Turning eighteen this week. Her mother's

planning a comeout for her next season. We can make it a wedding instead."

Edgerton eyed the other man thoughtfully.

"What do you mean? Are you suggesting that we arrange the whole thing

ourselves? Without consulting the parties involved?"

"If we consult them, it'll never come to

pass. Youngsters like ours don't ever agree to do what's good for 'em. We

elders know best about these things. I've never approved of offspring making

their own decisions on the subject of marriage anyway. All they do when one

broaches the subject with them is moon on about finding someone who engages

their affections. Affections, indeed! As if falling in love is anything more

than a temporary fit of insanity! Stuff and nonsense, all of that love rot.

When it comes to wedlock, anyone under the age of thirty should be made to

follow parental instructions."

Lord Edgerton looked dubious. "I don't

know, Birkinshaw. It's something I'd have to think over..."

"Think over? What can you want to think

over? I tell you, Greg, it'd be the making of both of them. A perfect solution

to our problems. Even my wife would agree that it's an ideal cure for her

worries about ..." But at that moment Lord Birkinshaw's expression clouded

over, for an important objection suddenly occurred to him. "Hang it all,

now I think of it, I don't suppose she would ... ! Oh, well, perhaps the idea

is a bit hasty."

"Hasty? Have you thought of some

impediment?"

"It suddenly occurred to me that my wife

might not see the matter as I do. She has great plans for Kitty, you know.

Expects her to make an advantageous match. These women don't think a fellow's

even eligible unless he's very well to pass. Hate to say it, my boy, but I

don't think she'd consider your brother-what's his name? Toby?-I don't think

she'd think Toby a promising prospect, his being a second son and all that

..."

"As to that, Birkinshaw, I've given the

second-son problem a good deal of thought. I don't approve of the practice of

settling one's entire fortune on the eldest son and letting the younger ones

drift off without a penny. It's a downright crime to ingrain in the younger

sons the habits of luxury and then abruptly cut them off from the wherewithall

to indulge them. I won't do that to my brother. I intend to deal fairly by him.

I plan to settle twenty thousand pounds on him. That would give him a quite

satisfactory income, and, in addition, he'll some day come into a very

substantial estate from his mother."