The Making Of The British Army (43 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

But in the decade and a half between the end of the Sudan campaign and the outbreak of the First World War – when, in the words of the official history, the British Expeditionary Force sailed for France as ‘the best-trained, best-organized and best-equipped British army that ever went forth to war’ – the army would suffer perhaps its greatest shock, from which it would emerge with an unprecedented passion for modernization. And again it would be a lesson taught by ‘the cheaper man’ – a mere 50,000 armed Dutch settlers or

boers.

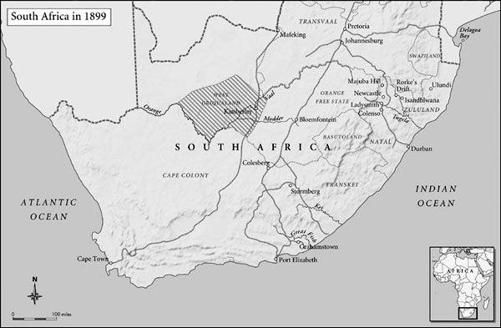

South Africa, 1899–1902

AS QUEEN VICTORIA APPROACHED HER DIAMOND JUBILEE SHE HAD RUEFUL

cause for satisfaction in her earlier warning to Gladstone that the nation had to be prepared for attacks and wars, somewhere or other, ‘CONTINUALLY’. The southern part of the African continent was as troublesome as the northern, and just as the nineteenth century had opened with fighting at the Cape, with British troops seizing the Dutch colony, so it would close with fighting on the Cape Colony’s vastly extended borders.

Those Dutch settlers (‘Boers’) who could not accept British rule had migrated during the course of the century, first east along the coast towards Natal, and then north towards the interior where they established two independent but linked republics – the Orange Free State and the Transvaal.

126

The Cape Colony was expanding, too, and in the footsteps of the Boer ‘fore-trekkers’. Britain annexed Natal in 1845 but recognized the independence of the two new Boer republics in the 1850s, though ambiguously in the case of certain rights, notably over foreign policy.

127

But the discovery of diamonds in 1867 near the Vaal

River changed the situation, triggering a ‘diamond rush’ that quickly turned Kimberley into a town of 50,000. In 1871 Britain annexed West Griqualand, the site of the bonanza, although the Boers disputed the claim since it lay inside what they considered were the natural, even if not recognized, boundaries of the Orange Free State. Six years later she annexed the Transvaal too.

The Transvaal Boers could do little to oppose the annexation since they were hard pressed fighting the Zulu on their north-east border; but in a magnificent example of the law of unintended consequences, they were able to impose terms in the aftermath of the British defeat of King Cetewayo in 1879. After a botched military operation by one of Wolseley’s ‘Ashanti Ring’, Major-General Sir George Colley, resulting in a famously sharp rebuff at Majuba Hill, the British authorities shrewdly cut their losses by abandoning full annexation in exchange for the Boers’ formal surrender of foreign policy. However, the discovery of massive gold deposits in 1886 soon put Transvaal back into the strategic limelight.

These annexations were not driven by simple cupidity; they were the logical response to what London and Cape Town perceived as the threat to British power in the region. This was the time of the ‘scramble for Africa’, with both French and German colonization giving growing cause for concern: gold- and diamond-rich anti-British (even pro-German) Boer republics on the borders of British South Africa were not a pleasing prospect. Friction between British South Africa and the Boer republics increased, not least because huge immigration into the Transvaal goldfields put the Boers in the minority, and they were reluctant to concede immigrants’ rights. From 1896 both republics began an armaments programme which was almost calculated to set them on a course for hostilities, given that the new-found gold was spent on Mauser rifles and Krupp artillery from Germany. And in the southern hemisphere’s October spring three years later, no longer willing to concede foreign policy to Britain, and confident of his military capability, Transvaal’s President Paul Kruger declared war.

To many a distant observer it looked like a war as ill matched as David’s fight with Goliath had first seemed. But David started well: when the Boer War was at last over, Kipling would write:

Let us admit it fairly, as a business people should,

We have had no end of a lesson: it will do us no end of good.

Not on a single issue, or in one direction or twain,

But conclusively, comprehensively, and several times and again.

In fact the lesson began on the first day of fighting in Natal. Boer mobilization had been straightforward. The fiercely independent burghers, as the citizens of both republics were known, had no regular army units apart from the

Staatsartillerie.

They simply assembled in their districts, each group forming a

komando

and electing officers, each man bringing his own rifle and horses. The day after declaration of war, 12,000 Transvaalers under General Piet Joubert, a cautious old veteran, crossed into Natal and began their advance along the railway line to seize the junction at Ladysmith, where they were to meet up with Commandant Marthinus Prinsloo advancing from the west with 6,000 Orange Free Staters. From Ladysmith they intended marching on Durban, and with Natal’s capital and only port in Boer hands, they were confident that Britain would sue for peace.

At first Joubert met no opposition – there were not even demolitions along the railway – and occupied the town of Newcastle on the fifteenth after a leisurely 30 miles’ march. From here he continued south towards Ladysmith in no great hurry (Prinsloo would not even cross the frontier for another three days), taking four days to cover only a further 20 miles. But the British scouts somehow failed to detect the strength of the advance, so that when shots were exchanged north of the mining centre of Dundee on the nineteenth, the commander there, Major-General William Penn Symons, believed the Boers to be a raiding party.

Penn Symons had a strong brigade at his disposal – four infantry battalions (two of them Irishmen, the Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Royal Dublin Fusiliers), three Royal Field Artillery batteries

128

and the 18th Hussars, plus 400 mounted infantry (MI) and the locally raised Natal Carbineers.

129

But Dundee was not an easy place to defend, surrounded as

it was on all sides by hills from which fire could be poured into the town. One observer wrote that it felt like being in a chamber pot.

Believing he faced only raiders, Penn Symons had withdrawn all his outlying pickets and patrols, so that before dawn on the twentieth 3,500 Boers under General Lucas Meyer – ‘the lion of Vreiheid’ – were able to climb the dominating Talana Hill undetected, though a mere mile or so north-east of the town. At first light they began shelling the British camp below with their Krupp field guns.

Penn Symons had not abandoned all field discipline, however: the brigade had stood to arms before dawn, with the 18th Hussars saddled and standing by their horses. He determined to attack the hill at once, with a short preparatory bombardment by his three artillery batteries, each of six Armstrong 15-pounder guns. And to cut off the Boer retreat, he ordered the 18th and the MI to make a wide flanking movement to the north of the hill. The plan was optimistic – the Boers outnumbered them and had all the advantage of the ground, as well as outstanding proficiency with the Mauser rifle – but it did at least have the merit of simplicity. Or, as one officer bitterly remarked later, all the originality of an Aldershot field day.

The 18th did, however, manage to get round the hill to a good position to enfilade the Boer line of escape, where they discovered 500 of the Boers’ led horses and ammunition details waiting patiently. One of the squadron leaders, Major Percival Scrope Marling, who had won a VC with the 60th Rifles in the Sudan in 1884, urged the commanding officer to open fire at once. But the commanding officer could not bring himself to give the order: to Lieutenant-Colonel Bernhard Möller, who had been commissioned into the regiment as a cornet twenty-seven years before, the notion of firing on riderless horses was abhorrent. Instead, he took his hussars further round the hill, east, across the Boer line of escape. At this point the second-in-command, Major Edward Knox, whose father had re-raised the regiment after the Indian Mutiny, remonstrated with Möller: their orders were to cut off a retreat, not to engage the enemy from the rear, if that was the commanding officer’s intention. They were heading into more trouble than they could deal with, Knox argued.

Meanwhile the infantry attack uphill against the Boers had faltered. With great but reckless courage, Penn Symons now galloped forward to urge on his men, and was himself killed. This, or perhaps the old infantry spirit returning, suddenly seemed to galvanize the brigade, which at last

began to make progress. But although each man carried the Lee – Metford rifle, they did not advance in movement covered by fire. Instead, led from the front by the regimental officers, they went up the hillside exactly as their forebears had at the Alma heights in the Crimea – almost as if on parade.

130

And just as the Russians took a terrible toll of the lines of red that day at the Alma, so too did the Boers of the lines of khaki. They might even have thrown back the assault for good had it not been for the Royal Artillery, who managed eventually to keep enough Boer heads down for the infantry to make progress. And as the sweating riflemen at last neared the top, the

komando

, whose tactical doctrine did not include standing their ground and fighting hand to hand, gave up the position and began streaming back down the hill, east towards the waiting ponies.

Möller, now realizing the peril he was in, decided to split his force, sending Knox with Major Scrope Marling’s squadron and another due south while he himself took the remainder (with the Maxims) north. Knox managed to manœuvre his half out of danger and rejoin the infantry, but Möller was caught 3 miles on by the Boer second echelon – some 2,500 men under General Hans Erasmus – who opened a very effective rifle fire from a commanding position on Impati Hill 3 miles north of the town. With casualties mounting by the minute, Möller decided to surrender. In a cruel irony, the regiment had wagered with another cavalry regiment on the passage south that they would be the first into Pretoria. They were, but they arrived by train as prisoners of war.

It had not been the best of starts – for either side. British losses were 200 wounded and over 50 killed on the slopes of Talana Hill, a high proportion of them officers, and 250 or so captured or missing, mainly from the 18th Hussars. On the other hand, although the Boers had suffered far fewer casualties they had quit the field. But if the British had shown the Boers that marching through Natal was not going to be easy, the Boers had exposed serious shortcomings in the British ability to coordinate fire with manœuvre. Courageous leadership from the front and the bravery of private soldiers were not going to be enough to defeat Boer marksmanship.

In the days after Talana Hill there was a deal of galloping and skirmishing, and though overall it was inconclusive, three ‘names’ of the First World War made their reputations. A column of Free Staters

had managed to seize the station at Elandslaagte between Ladysmith and Dundee, cutting the Dundee garrison’s lines of communication. Brigadier-General Ian Hamilton – who would command the ill-fated Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at Gallipoli – was sent to eject them with a brigade of three infantry battalions and artillery. In support was a cavalry brigade under command of Brigadier-General John French, who would command the British Expeditionary Force in 1914; his brigade major (chief of staff) was Douglas Haig. The Boers at Elandslaagte held their ground rather longer than Meyer’s had at Talana Hill, but were eventually driven off with the bayonet, and then harried by sabre and lance – the only occasion during the war on which a cavalry charge made real contact. French was feted for the

élan

and shrewdness with which he had handled the cavalry (in which glory Haig shared), as well as for a deal of personal courage, and Hamilton was lauded for his skill and bravery in manœuvring his infantry. Hamilton, indeed, was recommended for the VC for a second time in his career, but the citation was apparently rejected on the grounds that it might encourage other senior officers to take too many personal risks; Penn Symons had, after all, been killed only the day before.