The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes Adventures (82 page)

Read The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes Adventures Online

Authors: Mike Ashley

He was shaking from head to foot, panting for breath.

“Your Highness,” I said firmly, grasping his arm, “you should be in bed.”

“No, no, doctor, I cannot. Not until I have found it. I cannot otherwise answer, you understand … No, no, no!”

Between the three of us we finally managed to get the poor prince into bed, and, with Hans on one side and I on the other, to keep him under the covers until exhaustion at last claimed him. The respite, I knew, would be brief.

Meanwhile Holmes had quickly gone through the prince’s outer clothing, removed a small ring of keys from a buttoned pocket, and returned to the office. When I joined him, he was sitting at the desk, on which now lay neat piles of papers, staring thoughtfully at one page, which had been ruled off into regular squares, all filled with letters.

“Your verdict was correct, Holmes,” I said. “The prince is very sick and I’m afraid worsening.”

Holmes looked at me with distant eyes in which awareness of my presence only slowly dawned. “Do you know the cause?”

“Some kind of influenza, I think,” I replied. “It’s spreading fast among the troops on both sides of the front.”

“The outcome?”

“Some survive, though few when they’re as close to pneumonia as the prince.”

“Pneumonia,” Holmes repeated grimly. “So at best he’ll be incapacitated for days. Can you do nothing to hasten recovery? Time is so precious, Watson, even hours may make the difference between whether hundreds – thousands – live or die.”

“I have had some small success with injections of morphine,” I said. “I have nothing else.”

“Then by all means try the injections, doctor. I had hoped that the prince might come to himself long enough to remember something – anything – that would help me with this, but …” He handed me the following.

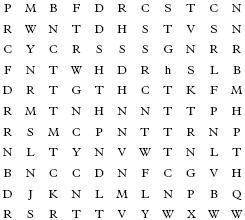

I stared at the meaningless rows of consonants in bewilderment. “

This

is the latest message from the President of the United States?”

Holmes nodded. “I believe so. Certainly it is on American paper, was stored in a locked inner drawer of the prince’s desk, and is obviously in code.”

“Then what had the prince lost? Or was that merely a delusion of his illness?”

“Far from it, doctor. What he had lost – to be precise, what Count Hoffenstein carried away with him – is the key to this and all such communications from the American president. The prince kept it, as he said, in an inner pocket, and had no doubt just taken it out in order to read this message with its aid when the count forced his way past Hans and entered.

“Whether or not the count knew that the prince had, moments before, received this page from the president I do not know, thought I should think it highly likely. Certainly he used the prince’s near delirium to remove the paper from wherever the prince had hastily shoved it – child’s play for a man like the count.”

I looked again at the page I held, with no more enlightenment than before. “What on earth would the key to this be like?”

“A page of lightly transparent paper of the same size and shape and with the same squares ruled on it, but with the random letters that are added as mere disguise blacked out. By placing that page over this, one can see at once the letters that form the true message.”

“There are no vowels,” I pointed out.

“Not necessary.” Holmes scribbled on a notepad and handed it to me. “Can you read that?”

He had written HLMSNDWTSN. “Holmes and Watson,” I said.

“Precisely.”

I stared back at the page of filled squares. “Without the key is it hopeless?”

“I won’t concede that, doctor. It is only the pressure of time that worries me. At least we do start with some advantages.”

“I can see none, Holmes, absolutely none.”

Holmes tapped the top left and bottom right of the page. “We know that this is a personal message from the American president to the German chancellor. Since the first two letters here are PM and the last WW, surely it is probable that these stand for Prince Max and Woodrow Wilson.”

“That is not much.”

“There are other assumptions that we can, I think, safely make. For instance, since the prince is fluent in English and the president not in German, almost surely the language used is English. Also, though the two are naturally of the highest political status, they are amateurs in the employment of codes. Therefore the device selected is apt to be simple.

“Further, even sending such pages as this between them is becoming increasingly difficult to arrange safely: Count Hoffenstein will not be the only spy on the watch along the route. Therefore the same code will most probably have been meant for all their covert communications, meaning that ample space will have been allowed. You will note that the last three lines of the squares on this page have the consonants interspersed in regular alphabetical order, from B to X. That almost surely indicates that the message is contained in only the first eight lines.

“We ’re not beaten yet, doctor. Not while we both have work to do.”

With that I certainly agreed, though heaving a deep sigh at our chances of success. I returned to the prince, who was struggling to get out of bed, and administered a small dose of morphine.

Though this quickly quietened him, he still had periods in which his whole body jerked, his eyes fluttered uneasily, and he would cry out thickly, “Where … where … where …” as long as he could find breath. These symptoms ceased after the second injection, but his breathing became increasingly strained, his face even more flushed, his skin burning. He was, for good or ill, nearing the crisis of his illness.

Hans was invaluable during these hours, doing unquestioningly whatever I bade. Even when, all else seeming to be failing, I turned to that simple nursery remedy of alternating hot and cold fomentations high on the chest and low on the back, for an hour at a time.

When not actively engaged in such tasks, Hans stretched out at the foot of his master’s bed, alert to the smallest move or sound. I dozed in a chair by the fire; if my waking thoughts were on my patient, those in my moments of haze were filled with an endless parade of consonants.

Concede that the secret message began with “Prince Max,” yet what words or words was hidden within bfdrcstcn that completed the first line? Certainly nowhere in the message had I been able to decipher either the Kaiser’s name or title, and yet I would have expected that Queen Victoria’s deluded grandson would be a major topic of such a message.

For, as long as he refused to accept the reality of Germany’s sure defeat, and as long as the officer corps retained their steadfast devotion to their oath of loyalty (how praiseworthy a trait had only the man and the cause been worthy!), the war would continue, for weeks, even months. Literally buckets of blood would pour forth in every dressing station across the front, and that would be only from those who survived long enough to be brought to such medical oases.

Sometime toward evening I went back into the office to tell Holmes of the prince’s continuing struggle: like the world, he was in but not yet through the darkest hour. I found Holmes still seated at the desk, still frowning down at that page of lettered squares, and above him swirled the blue smoke of his pipe. I returned to the bedside.

Near evening, following more hot and cold fomentations, the prince’s breathing eased. Could I hope that he would shortly rouse enough to be able, even briefly, to assist Holmes? Dare I try to force my patient to that point? I decided the risk was not worth it: the prince was too ill, my faith in my friend too great. Instead I administered another dose of morphine.

As the second dawn brought a trace of blue to the sky’s blackness, Hans woke me, tears of joy streaking his old face, and led me to the prince’s bedside. The drugged coma had faded into genuine slumber, the chest rose and fell naturally, the cracked lips were tinged with a normal pink. The Chancellor would recover.

I hastened to tell Holmes the good news, and found the office and the adjacent rooms all deserted. The guard in the antechamber told me that “the other English Herr” had gone out hours ago.

Did that auger well or not? Who could say?

In a couple of hours the prince awoke with that weak and unquestioning acceptance of everything that marks the early recovery from serious illness. I wanted to order a bowl of gruel for him, but Hans would have none of it: his master hated gruel and should have hot bread and milk, made as only Hans could make it, with honey.

“And coffee, please,” the prince murmured, a clasp of the hand showing his gratitude for his old servant’s devotion.

I willingly agreed, and was myself devouring sandwiches when Holmes walked in unannounced.

“I am pleased to see you better, Your Highness,” he said to Prince Max with his customary calm. “May I put on the wireless? An announcement from the palace is expected momentarily.”

We waited motionless, all four, as the moments that seemed like hours passed. Then the music – one of the more sombre selections of Bach, as I recall – was abruptly cut off, and in hushed tones a man’s voice stated that the Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, had just issued a statement: His Most Gracious Majesty Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated, and all the royal princes agreed to renounce the throne in the cause of peace.

Prince Max and Holmes exchanged a long and ultimately understanding gaze. At last with a little sigh the prince said, “So His Majesty wouldn’t see you, either. Even at the last.”

“What can you expect”, I said, with the bitterness of four years, “from a man who has never been in battle and who yet would sport a huge golden helmet?”

The prince gave a small smile. “Spoken like a true Englishman, Dr Watson. I am greatly relieved at what you have done, Mr Holmes, for I fear that I could not have. Necessary though I can see that it was.”

“I think you would have done so, Your Highness, if you had seen the growing turmoil in the streets and also read the message from President Wilson.”

Slow and painful memory grew in the prince’s tired eyes. “I had asked what the terms would be for the end of the war and had just had his reply – I remember that, though I had had no time to decipher the message when the count arrived. You found the key to the code, then, Mr Holmes? Where was it?”

“I fear in Count Hoffenstein’s pocket, Your Highness.”

The prince passed a weak hand across his face. “Somehow I am not surprised. We have never been intimate, yet he shook my hand so heartily before leaving! No doubt in order to remove the key that I had pushed under the blotter on my desk. However did you manage to read the message, Mr Holmes?”

“With more effort than it should have taken, Your Highness. The trick in making out such a code, you understand, is to run through all possible combinations of the letters, adding vowels as required, until words are formed.

“All I could see at first was

score,

shortly extended to

fourscore.

I couldn’t imagine President Wilson using such arcane language, yet I could make nothing else out from the first letters. Then I realized that the squares unneeded for the message had not been filled at random, as is usual, but with words that, while not part of the communication to Your Highness, yet meant much to the President of the United States. What would such a man at such a time quote that begins with

fourscore

?”

“ ‘Fourscore and seven years ago,’ ” Prince Max promptly began, “ ‘our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation

“ ‘Conceived in liberty,’ ” Holmes finished.

“The start of the Gettysburg address!” I exclaimed.

“I could have told you that and saved much time and trouble,” the prince observed sadly, “if I had been able.”

“That could not be helped, Your Highness. When the consonants of the address are taken out, what remains are those that form the president’s message, his reply to your question as to what would be needed to end the war. ‘Abdication without succession. Renewed Allied attack imminent. Prompt reply vital.’ ”

“ ‘Prompt reply’!” the prince breathed, “and I was delirious! Mr Holmes, very many owe you great thanks. Did you have any difficulty in convincing the chief of our wireless services that your order came from me?”

“Oh, I have friends everywhere,” Holmes replied vaguely. “Also I had taken the liberty of using Your Highness’ stationery.”

And, I was sure, of forging the prince’s handwriting with mastery skill.

“The last time I called on the Kaiser,” Prince Max observed sadly, “he sent out word that he couldn’t see me as it was already seven o’clock and he was late in dressing for dinner. It was then five minutes past midnight. I fear it has been five minutes past midnight for my poor country for a long time, Mr Holmes. What is the date?”

“The tenth of November, Your Highness. All should be concluded tomorrow.”

“Hans, champagne.” We raised our glasses. “To the eleventh of November,” Prince Max said with tears in his eyes. “May the world never forget.”

That is why I pen these lines, so that the part that Sherlock Holmes played in those final days may be known to all.

May the world never forget.

After this case Holmes retired again to his cottage in Sussex. Watson paid him the occasional visit but they were both now in their seventies and travelling became tiresome. By 1926 Watson had finished compiling the last of his notes. The final published story, “Shoscombe Old Place” appeared in the March 1927

Strand Magazine.

Watson died soon after, but Holmes’s remarkable constitution kept him active well into the 1930s. It is somewhat bizarre that no death certificate exists for Sherlock Holmes, but I do know that his cottage in Sussex was sold in August 1939, just before the outbreak of the Second World War. Holmes was, by then, about eighty-six and is unlikely to have been involved in any further war-time investigations, but the fact that his death is not recorded in the United Kingdom is suggestive that, just before the outbreak of War, he emigrated. Where to and why I do not know. No doubt he had decided it was time for one last great adventure.