The Man Who Left Too Soon: The Life and Works of Stieg Larsson (37 page)

Read The Man Who Left Too Soon: The Life and Works of Stieg Larsson Online

Authors: Barry Forshaw

‘Frankly, I’m damned sure that if he had lived he would have done some pretty judicious editing himself on the books – after all, he was a respected journalist who knew precisely how to get a point across with concision in his articles.’

But does the author always know what’s best for his own work? After all, if Larsson had lived he might, for instance, have insisted that his original Swedish title,

Men who Hate Women

, would have to be used in translated editions (had he had the power to insist on such a thing). And surely the three English language titles beginning with the words ‘

The Girl

…’ are one of the things that so grasped the public imagination? Larsson’s original title is surely redolent of something like a Marilyn French book of the 1970s, when feminism was in its most combative and male-hostile period?

‘Yes, it’s a point worth considering,’ Val McDermid continued. ‘There is no question that the renaming of the books was a masterstroke. But then there was another masterstroke in Larsson’s recipe for success, and it’s a rather macabre one: Stieg Larsson dying at 50, before any of his books were published. It is unquestionably true that this sad waste of a life is something that caught the consciousness of readers. And it’s one of the first things that people talk about when recommending the books to others – sometimes at the same time as extolling their virtues. It’s not a career move that I can say has appealed to me, but it undeniably adds to people’s legends. From Mozart to James Dean and Marilyn Monroe – those who died relatively young will always have us speculating what else they might have achieved had they lived. By all accounts, Larsson planned a ten-book sequence – and it’s intriguing to think how he might have developed the characters. Having said that, the trilogy – which is what it ended up being – works very well as a trilogy, and who’s to say that he might not have lost the elements that make the first three books work so well?

‘I suppose I’m luckier than Stieg; what forced me to start looking at my mortality was being diagnosed with osteoarthritis in my knees at the age of 38. I realised I was not invincible, and that unless I changed the way I was living, I was not going to make old bones. By all accounts, Stieg never had that reckoning with himself. Having been a journalist myself, I know that as a profession we’re inclined to be careless of our health. That’s not to say that novelists can’t behave in a similar fashion – Michael Dibdin, who wrote such wonderful crime novels, clearly didn’t look after himself, and died at a relatively young age. It’s hard not to be annoyed at talented people who are spendthrift of their health – Dibdin, like Larsson, probably had a lot of good books in him which he was never to write.

‘There is, of course, another element that one cannot forget where Larsson was concerned: the political. It’s something else that we have in common, apart from the kind of books we’ve both written – I was and am very much a political animal, though perhaps I was more a political pragmatist than Stieg was.

‘Like him I was on the fringes of politics for quite a long time – at university I was part of the student and trade union movements. But as I said, I was always on the pragmatist side rather than the theoretical side. My overriding impulse was always: what can we achieve? What practical thing can we do to actually make people’s lives better? I’m not sure that this was true of the circles Stieg moved in, but I’ve always found the trouble with the radical Left was that the women were still expected to make the tea. That’s not to say that everyone would not have espoused feminist values, it was just lower down on the agenda: “We’ll get to doing things for women when the important things are done…”

‘On the other hand, Stieg was very much concerned with attitudes to women in his magazine articles; he’d talk about how (for instance) the far Right would say “feminism was destroying Christianity” – to which I’d say, “Bring it on! What’s the problem?” But seriously, it was perfectly obvious that improving the treatment of women in society was an absolutely crucial tenet for him.

‘One could say that his change of career from a journalist to novelist – although he didn’t live to see the second career flourish – was in some ways a very apposite move. Fiction possibly changes lives more than journalism because of the way it sucks you in emotionally. After all, people who read right-wing newspapers in the UK such as the

Daily Mail

are having their prejudices and attitudes confirmed – that’s the

raison d’être

of a paper like that (as it is, I suppose, of left-wing papers such as the

Guardian

). The opinions of readers are confirmed and justified on a day-to-day basis – what they already believe. Whatever our viewpoint may be, I think many of us read novels in a more open state, with political decision-making kept somewhat at bay. And if a good novelist can spring a provocative idea on the reader – within the context of a gripping narrative – it is just possible that attitudes can be changed, or at least confronted. Look, for instance, at how many crime readers – myself included – avidly read the novels of P D James and Ruth Rendell, whose social politics are totally different (in Parliament, they sit on opposite sides of the House).

‘And if Stieg and I are political writers, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we would alienate readers of other, different political persuasions – at least not in the way that political writing in a newspaper would. If you’re about to draw readers into a novel, and you say something nice about something they disapprove of, it doesn’t mean that they will stop reading. When I wrote

A Darker Domain,

which dealt with the very divisive miners’ strike in Britain in the 1970s, there were people coming up to me in the south of England who were saying “I had no idea things were so bad in the mining communities”. And I didn’t create a sentimental vision of the miners, I think I painted a warts-and-all picture. For instance, I was very critical of the miners’ leaders – you could paraphrase the famous observation about “lions being led by donkeys”.

‘Important issues can be discussed in the context of the novel – and the novelist can give you all sides of an argument, along with key insights. And to some degree, I think that is one of the things that Stieg Larsson does in his books – he grants us an insight into a society that we think we know – but really have an incomplete view of.

‘What really intrigues me is: where was he coming from? I would have loved to talk to him about so many things – something, of course, I can’t do now. Often when you find writers who feel almost obsessively about certain issues, there is something about childhood which has provoked or formed that attitude. Stieg lived with his grandparents as a child, for instance, until he was nine years old – that would have affected me, and I would love to talk to him about what he took from that – what his response was as a child, then as an adult. And feminism, of course – I know that there was a lot of suspicion in the women’s movement about men who were sympathetic, and who hung around with women. Rather than being applauded, the response sometimes was “Is this the only way you can get laid?”

‘Regarding the moment in Stieg Larsson’s life when he became the passionate feminist he was, I’m reminded of something involving one of the great crime writers of the past, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. There was an incident that changed the way he looked at the world. When he was a war correspondent during the First World War, he went with Rebecca West to a factory in the west of Scotland where they made cordite – in fact the factory was nine miles long, the biggest factory of its kind in the world. Most of the factory workers were of necessity women, as so many of the men were at the front. And seeing women working under often hazardous conditions, and being such a key part of the war effort, he said decisively “Women should get the vote. They have a perfect right to say what’s what when peace comes.” In fact, that is the precise point at which Conan Doyle became a feminist.

‘Of course, however radical you think yourself (and I’m sure that Stieg Larsson, like me, would like to think that he would always be an anti-establishment figure) the danger is actually about becoming just the opposite – something, of course, that he never had time to do.’

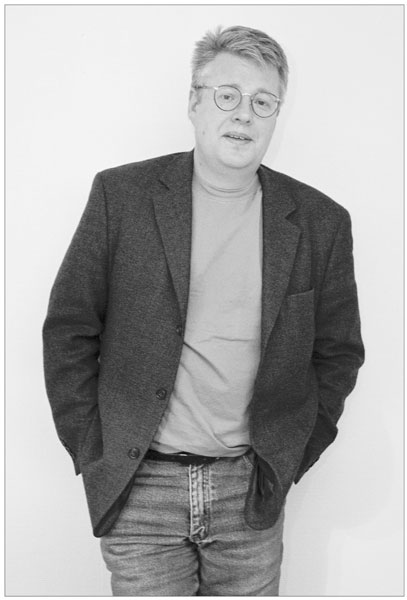

The man who left too soon – a portrait of Stieg Larsson taken in Stockholm in 2004, the year he died.

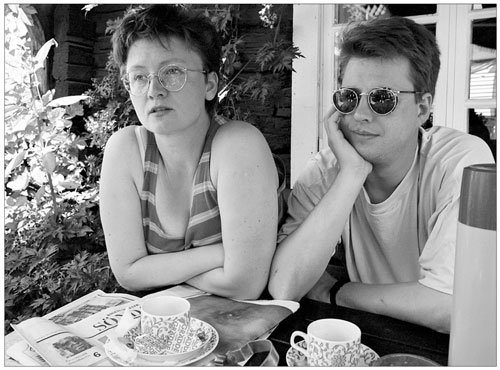

Larsson and his long-term partner, Eva Gabrielsson, relaxing over a cup of coffee in Strängnäs, Sweden.

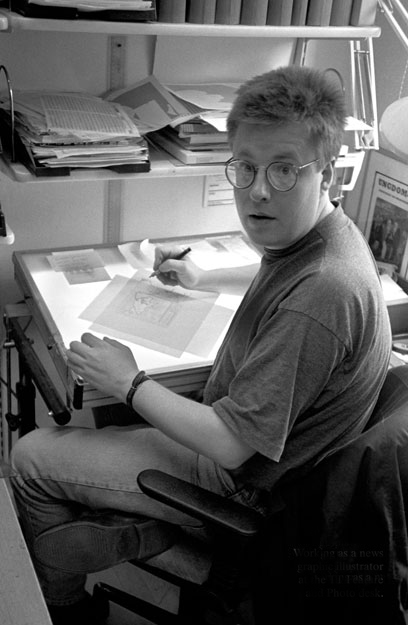

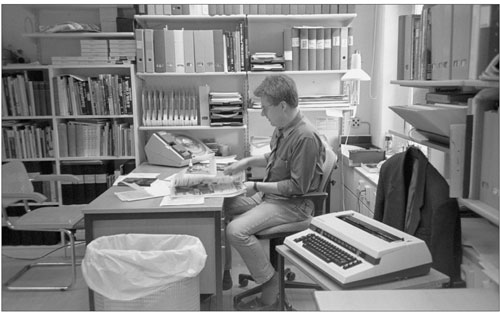

At work at TT, the Swedish news agency, in Stockholm in the mid-1990s.

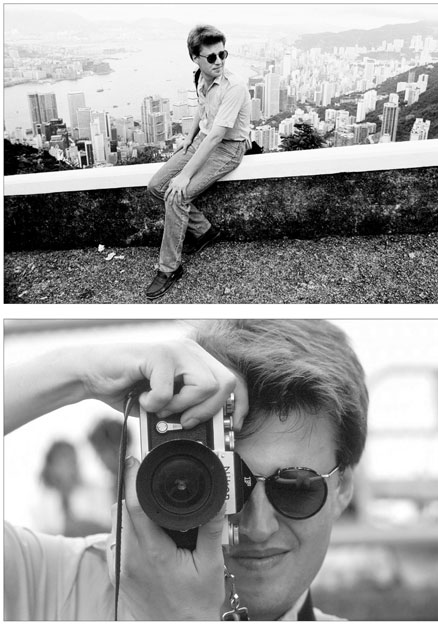

On a visit to Hong Kong, August 1987.

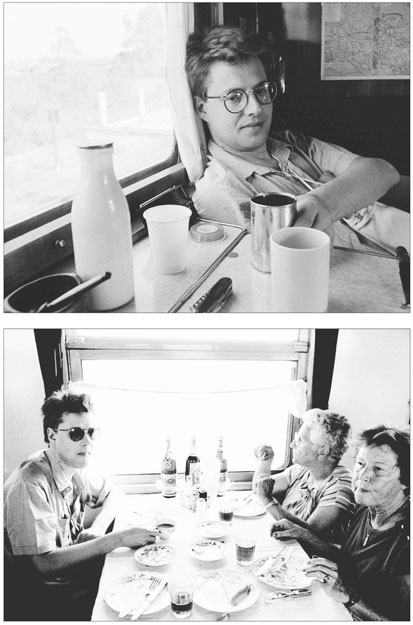

Larsson on the Trans-Siberian Railway, July 1987.