The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda (48 page)

Read The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda Online

Authors: Devin McKinney

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Actors & Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Movies, #Biographies, #Reference, #Actors & Actresses

* * *

Drifts.

Story’s almost over.

But I have seen the elephant.

* * *

The shape leans over him and smiles. The face asks how he feels. He says he is fine. He says he feels no pain.

* * *

Henry dies at 7:55 on the morning of August 12, 1982. The certified cause is cardiorespiratory arrest—“respiratory failure brought on by heart disease.” Shirlee is at his bedside; Jane and Peter are en route to the hospital.

Later that day, wife and children gather outside the Chalon Road house for a brief announcement to the press.

“He had a good night,” Shirlee says. “He talked with all of us and he was conscious at all times. He woke up this morning, he sat up, and just stopped breathing.”

* * *

Obituaries are run on the late news, and statements of tribute heard from Barbara Stanwyck, Charlton Heston, Bette Davis, Lucille Ball, Jane Alexander, David Rintels, and others. Cedars-Sinai is flooded with calls from admirers wishing to send flowers and condolences. “People really loved him,” says a hospital spokeswoman.

From President Reagan come these words:

Nancy and I were deeply saddened to learn of Henry Fonda’s passing today. Henry Fonda was a true professional, dedicated to excellence in his craft, whose skill and precision as an actor entertained millions. Throughout his long and distinguished career Henry Fonda graced the screen with a sincerity and accuracy which made him a legend. We will miss Henry and extend a deep sympathy to his family.

In the USSR, the government paper

Izvestia

reports the death of “a noted American actor.”

Corriere della Sera

of Milan, Italy’s largest daily newspaper, remembers Fonda as “a democratic figure in the jungle of the movie world.”

La Stampa

of Turin calls him a “civil and proud hero.”

“I’ve just lost my best friend,” Jimmy Stewart says.

* * *

A week later, the contents of Henry’s will—executed on January 22, 1981—are announced. It bequeaths $200,000 to daughter Amy Fonda Fishman, with the remainder of the estate and all personal effects going to Shirlee. The stipulation is made that, should Shirlee die within ninety days, the estate will go to the Omaha Community Playhouse. No bequests are made to Jane or Peter, on presumption of their financial independence.

Henry’s eyes will be donated to the Manhattan Eye Bank.

As for burial or funeral services, there will be none. Henry Fonda has specified, in the plainest language, that his bodily remains be “promptly cremated and disposed of without ceremony of any kind.”

* * *

In a fragment titled “The Old Man Himself,” dated 1891, Walt Whitman held forth:

Walt Whitman has a way of putting in his own special word of thanks, his own way, for kindly demonstrations, and may now be considered as appearing on the scene, wheeled at last in his invalid chair, and saying,

propria persona,

Thank you, thank you, my friends all.… One of my dearest objects in my poetic expression has been to combine these Forty-Four United States into One Identity, fused, equal, and independent. My attempt has been mainly of suggestion, atmosphere, reminder, the native and common spirit of all, and perennial heroism.

One of the last projects Henry Fonda considers, we’re told by one researcher, is a solo show about Walt Whitman. Picture it—Henry, “wheeled at last in his invalid chair,” wearing the full beard of his final months. The blue eyes have lost their focus, yet they appear winsome, content on other visions: shapes, faces, colors. He is winding down, like a tough old animal or exquisite timepiece, but he has long outlived his father to become what George Billings impressed him as being—the old man in the shawl, who wept tears of history into his beard.

How would Fonda have rehearsed his Whitman? In the mirror? In his mind? Who would his Whitman have been—the song-poet of democracy, or the lusty bard of the meadows? And what passages would he have chosen? Studying the preface to

Leaves of Grass,

scanning the words with the rheumy eyes and ivory fingers of the old man himself, would Henry have lingered on these lines—

Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is.

—or these—

He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet.

—or these?

He says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you.

12

Omaha, 1919

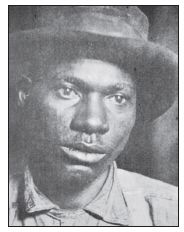

Will Brown

It was hours past sundown, but the Omaha sky on September 28, 1919, was bright with light: The Douglas County Courthouse was burning.

Starting in the afternoon, a mob of thousands had been laying siege to the building with stones, bricks, and Louisville Sluggers. Some had begun firing guns at the windows. Eventually, the mob had penetrated the courthouse and taken over the ground-floor rotunda, driving police and other city employees to the upper stories. The lines of a nearby service station were tapped, and the first floor sprayed with gasoline. Someone lit the first match.

The courthouse held the county jail, and the mob was demanding the surrender of a prisoner—a forty-one-year-old black laborer, Will Brown, under arrest for raping a white girl. In his courthouse office, Omaha’s mayor, Edward P. Smith, had been trying to contact government officials and secure federal troops. As yet, no aid had arrived. In a show of resistance to the mob, Smith had refused to leave his office, but finally the fire made it unsafe to stay.

Near eleven o’clock, the mayor emerged on the eastern steps to plead restraint and reason. But few could hear him.

Suddenly, a gunshot cut the din of voices.

“He shot me,” someone screamed—and fingers were pointing at Smith, whose hands were empty.

The mob converged on the mayor, forced him to the corner, got a rope around his neck, and, tossing the free end over a traffic light, tried to hang him.

* * *

In late 1918, thousands of black veterans had returned from the war, dressed proudly in the uniforms they had earned. Cheap automobiles and rail travel offered hope of mobility to poor families trapped in racist backwaters, and northward migration, as John Hope Franklin wrote, “spread like wild fire among Negroes.… It was estimated that by the end of 1918 more than one million Negroes had left the South.” They left for the urbanized North and Middle West to survive, but also because they felt possibilities opening for the first time in their lives.

But often, what they found on reaching cities like Chicago, Kansas City, and Omaha was bigotry in new forms. Labor unions resented having to share a job market already crowded with foreign immigrants. The Klan, exploiting the feeling, spread its tentacles to the Middle West. In the overlap of economics and mass migration, America grew rank with racial violence, usually expelled upon blacks spuriously charged with crimes against whites.

Racial terror was widespread in the spring of 1919. Race riots in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Chicago left hundreds dead in July alone. In Ellisville, Mississippi, John Hartfield was publicly burned at a predetermined hour, his mob execution announced ahead of time in the local paper. A number of lynching victims had served in the war. The murders were almost always preceded by drawn-out acts of torture, and medieval horrors committed by ordinary citizens became daily news. Writer-activist James Weldon Johnson looked on that season of blood and gave it the only name that fit: “Red Summer.”

* * *

Omaha had been Nebraska’s chief beneficiary of the northward migration, more than doubling its black population since 1910. The integration had not always gone easily, as striking white meatpackers were replaced by newly arrived black workers. An educated, activist black middle class was developing, but free intermingling occurred only in the bars and brothels of the city’s interracial underground.

Then, on September 28, at the climax of Red Summer, the mob lit up the Douglas County Courthouse and demanded Will Brown. At a window over the courthouse square, Henry Fonda, age fourteen, stood beside his father, William, and watched.

“It was so horrifying,” Henry would recall near the end of his life. “When it was all over, we went home.”

* * *

Three days earlier, Agnes Loebeck, a white girl who gave her age as nineteen, had filed a police report, claiming she’d been sexually assaulted by a gun-wielding black man on a street in South Omaha. The next day, Will Brown—identified as “an itinerant meatpacker” from Cairo, Illinois—was picked up on an anonymous tip, arrested, identified, and jailed.

The case was simple, yet it wasn’t. Whispers went round that Loebeck and Brown knew each other, in more than a passing way; that Brown had spurned her for another white woman; that a jealous Loebeck was taking her revenge. Brown was allowed a brief consultation with a black lawyer, H. J. Pinkett, who observed that the prisoner was hobbled by rheumatism—casting doubt on the feats of strength and speed attributed to him.

Men of power in Omaha saw the chance to exploit the case, for reasons that had little to do with the direct defense of white supremacy. John Gunther’s curious floating allusion to the city’s “lack of effective civic leadership” had its origins in this period, when the town was run by a ruthless political machine that made Omaha, in the words of a 1919 report in the black journal

The Crisis,

“perhaps the most lawless of any city of its size in the civilized world.”

* * *

Running the machine was a gambler named Tom Dennison, who had been in charge of graft in the vice-rich Third Ward since the 1890s. His front man was Omaha’s mayor, James Dahlman, known as “Cowboy Jim”—likewise a gambler, drinker, giver and taker of bribes, and for all that a protégé of Nebraska’s own William Jennings Bryan, presidential candidate and the era’s paragon of Christian piety. In their corner was the

Omaha Daily Bee,

most outspoken of the city’s three dailies, founded by Edward Rosewater in 1871. Conservative, Republican, and pro-Dennison, the paper was also antilabor and antiimmigrant—despite Rosewater’s being a native of Czechoslovakia, real name Rossenwasser.

Dahlman ran essentially unopposed for a decade, and Dennison’s “sporting district,” centered at Harney and Sixteenth streets, just blocks from the courthouse, thrived. But after statewide prohibition passed in 1916, the rhetoric of reform led to city laws that cut into Dennison’s power. Two years later, Dahlman was ousted by Democrat and reform candidate Edward P. Smith.

Ed Smith appointed as police commissioner fellow reformer J. Dean Ringer, who instructed his men to raid Dennison’s houses. Smith also embraced the NAACP, whose Omaha chapter was founded on his watch. Such tolerance endeared him neither to the police nor to white laborers angry at black migrants who had taken their jobs during a recent meatpackers’ strike.

Dennison formed the strategy of subverting Smith by exploiting racial tension. Between June and September, the

Daily Bee

published twenty-one separate allegations of assaults on women; twenty of the claimants were white, with sixteen assailants identified as black. It also reported copiously on racial attacks around the country, giving them an alarmist, retributive spin: The riot in Washington, D.C., Omahans were informed, had begun as “retaliation for recent attacks by blacks on white women.” The paper also ran Chief of Police (and Dennison appointee) Marshal Eberstein’s warning to an NAACP gathering that if “the good colored people” of Omaha did not aid in the apprehension of “the negroes responsible for the numerous recent assaults on white women,” a deadly riot of the kind lately seen in East St. Louis, Illinois, might well occur in Omaha.

When Agnes Loebeck’s charges hit the city room at the

Daily Bee,

someone there may have paused to feel the weight of the moment: Red Summer had come to town.

* * *

Two afternoons later, a group of youths gathered outside a school in South Omaha and began marching to the jail. En route, adults, both men and women, joined in; by the time it reached the courthouse—protected by a meager ring of thirty policemen—the mob numbered in the thousands.

They began by shattering all the windows on the first two floors and storming the doors. Inside were forty-five additional policemen; when the main entrance was breached and the rioters took the rotunda, the officers retreated up the stairs. By this time, stones had been replaced with guns. Police at the third- and fourth-floor windows returned fire, killing a sixteen-year-old rioter in the rotunda, as well as a businessman a block away. A young man was seen riding a white horse in and out of the square, flashing a rope and exhorting the rioters.

Around eight-thirty, the ground floor was set afire. When fire wagons appeared, the crowd prevented them from entering the square; firefighters were forced back, and their hoses severed. City employees scrambled to higher floors. Some were seen phoning their families to say good-bye.