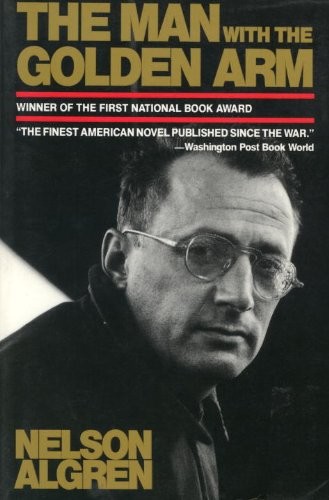

The Man With the Golden Arm

Golden Arm

Nelson Algren

According to the diary of my wife Jill Krementz, the photographer, the young British-Indian novelist Salman Rushdie came to our house in Sagaponack, Long Island, for lunch on May 9th, 1981. His excellent novel

Midnight’s Children

had just been published in the United States, and he told us that the most intelligent review had been written by Nelson Algren, a man he would like to meet. I replied that we knew Algren some, since Jill had photographed him several times and he and I had been teachers at the Writers’ Workshop of the University of Iowa back in 1965, when we were both dead broke and I was forty-three and he was fifty-six.

I said, too, that Algren was one of the few writers I knew who was really funny in conversation. I offered as a sample what Algren said at the Workshop after I introduced him to the Chilean novelist José Donoso: ‘I think it would be nice to come from a country that long and narrow.’

Rushdie was really in luck, I went on, because Algren lived only a few miles to the north, in Sag Harbor, where

John Steinbeck had spent the last of his days, and he was giving a cocktail party that very afternoon. I would call him and tell him we were bringing Rushdie along, and Jill would take pictures of the two of them together, both writers about people who were very poor. I suggested that the party might be the only one that Algren had given himself in his entire life, since, no matter how famous he became, he remained a poor man living among the poor, and usually alone. He was living alone in Sag Harbor. He had had a new wife in Iowa City, but that marriage lived about as long as a Junebug. His enthusiasm for writing, reading and gambling left little time for the duties of a married man.

I said that Algren was bitter about how little he had been paid over the years for such important work, and especially for the movie rights to what may be his masterpiece,

The Man

with the Golden Arm

, which made huge amounts of money as a Frank Sinatra film. Not a scrap of the profits had come to him, and I heard him say one time, ‘I am the penny whistle of American literature.’

When we got up from lunch, I went to the phone and dialed Nelson Algren’s number. A man answered and said, ‘Sag Harbor Police Department.’

‘Sorry,’ I said. ‘Wrong number.’

‘Who were you calling?’ he said.

‘Nelson Algren,’ I said.

‘This is his house,’ he said, ‘but Mr. Algren is dead.’ A heart attack that morning had killed Algren at the age of seventy-two.

He is buried in Sag Harbor – without a widow or descendants, hundreds and hundreds of miles from Chicago, Illinois, which had given him to the world and with whose underbelly he had been so long identified. Like James Joyce, he had become an exile from his homeland after writing that

his neighbors were perhaps not as noble and intelligent and kindly as they liked to think they were.

Only a few weeks before his death, he had been elected by his supposed peers, myself among them, to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters – a certification of respectability withheld from many wonderful writers, incidentally, including James Jones and Irwin Shaw. This was surely not the first significant honor ever accorded him. When he was at the peak of his powers and fame in the middle of this century, he regularly won prizes for short stories and was the first recipient of a National Book Award for Fiction, and so on. And only a few years before his death the American Academy and Institute had given him its Medal for Literature, without, however, making him a member. Among the few persons to win this medal were the likes of William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway.

His response to the medal had been impudent. He was still living in Chicago, and I myself talked to him on the telephone, begging him to come to New York City to get it at a big ceremony, with all expenses paid. His final statement on the subject to me was this: ‘I’m sorry, but I have to speak at a ladies’ garden club that day.’

At the cocktail party whose prospects may have killed him, I had hoped to ask him if membership in the American Academy and Institute had pleased him more that the medal. Other friends of his have since told me the membership had moved him tremendously, and had probably given him the nerve to throw a party. As to how the seeming insult of a medal without a membership had ever taken shape: this was nothing but a clumsy clerical accident caused by the awarders of prizes and memberships, writers as lazy and absentminded and idiosyncratic in such matters as Algren himself.

God knows

how

it happened. But all’s well that ends well, as the poet said.

Another thing I heard from others, but never from Algren himself, was how much he hoped to be remembered after he was gone. It was always women who spoke so warmly of this. If it turned out that he head never mentioned the possibility of his own immortality to any man, that would seem in character. When

I

saw him with men, he behaved as though he wanted nothing more from life than a night at the fights, a day at the track, or a table-stakes poker game. This was a pose, of course, and perceived as such by one and all. It was also perceived back in Iowa City that he was a steady and heavy loser at gambling, and that his writing was not going well. He head already produced

so

much

, most of it in the mood of the Great Depression, which had become ancient history. He appeared to want to modernize himself somehow. What was my evidence? There he was, a master storyteller, blasted beyond all reason with admiration for and envy of a moderately innovative crime story then appearing in serial form in the

New

Yorker

, Truman Capote’s

In Cold Blood

. For a while in Iowa, he could talk of little else.

While he was only thirteen years my senior, so close to my own age that we were enlisted men in Europe in the same World War, he was a pioneering ancestor of mine in the compressed history of American literature. He broke new ground by depicting persons said to be dehumanized by poverty and ignorance and injustice as being

genuinely

dehumanized, and dehumanized quite

permanently

. Contrast, if you will, the poor people in this book with those in the works of social reformers like Charles Dickens and George Bernard Shaw, and particularly with those in Shaw’s

Pygmalion

, with their very promising wit and resourcefulness and courage. Reporting on what he saw of dehumanized Americans with his own eyes day after day, year after year, Algren said in effect, ‘Hey – an awful lot of these people your hearts are

bleeding for are really mean and stupid. That’s just a fact. Did you know that?’

And why didn’t he soften his stories, as most writers would have, with characters with a little wisdom and power who did all they could to help the dehumanized? His penchant for truth again shoved him in the direction of unpopularity. Altruists in his experience were about as common as unicorns, and especially in Chicago, which he once described to me as ‘the only major city in the country where you can easily buy your way out of a murder rap.’

So – was there anything he expected to accomplish with so much dismaying truthfulness? He gives the answer himself, I think, in his preface to another novel,

Never Come Morning.

As I understand him, he would be satisfied were we to agree with him that persons unlucky and poor and not very bright are to be respected for surviving, although they often have no choice but to do so in ways unattractive and blameworthy to those who are a lot better off.

It seems to me now that Algren’s pessimism about so much of earthly life was Christian. Like Christ, as we know Him from the Bible, he was enchanted by the hopeless; could not take his eyes off them, and could see little good news for them in the future, given what they had become and what Caesar was like and so on, unless beyond death there awaited something more humane.

PART ONE

KUPRIN

Do

you understand, gentlemen, that all the horror is

in just this – that there is no horror!

The captain never drank. Yet, toward nightfall in that smoke-colored season between Indian summer and December’s first true snow, he would sometimes feel half drunken. He would hang his coat neatly over the back of his chair in the leaden station-house twilight, say he was beat from lack of sleep and lay his head across his arms upon the query-room desk.

Yet it wasn’t work that wearied him so and his sleep was harassed by more than a smoke-colored rain. The city had filled him with the guilt of others; he was numbed by his charge sheet’s accusations. For twenty years, upon the same scarred desk, he had been recording larceny and arson, sodomy and simony, boosting, hijacking and shootings in sudden affray: blackmail and terrorism, incest and pauperism, embezzlement and horse theft, tampering and procuring, abduction and quackery, adultery and mackery. Till the finger of guilt, pointing so sternly for so long across the query-room blotter, had grown bored with it all at last and turned, capriciously, to touch the fibers of the dark gray muscle behind the captain’s light gray eyes. So that though by daylight he remained the pursuer there had come nights, this windless first week of December, when he had dreamed he was being pursued.

Long ago some station-house stray had nicknamed him Record Head, to honor the retentiveness of his memory for forgotten misdemeanors. Now drawing close to the

pension years, he was referred to as Captain Bednar only officially.

The pair of strays standing before him had already been filed, beside their prints, in both his records and his head.

‘Ain’t nothin’ on

my

record but drunk ’n fightin’,’ the smashnosed vet with the buffalo-colored eyes was reminding the captain. ‘All I do is deal, drink ’n fight.’

The captain studied the faded suntans above the army brogans. ‘What kind of discharge you get, Dealer?’

‘The

right

kind.

And

the Purple Heart.’

‘Who do you fight with?’

‘My wife, that’s all.’

‘Hell, that’s no crime.’

He turned from the wayward veteran to the wayward 4-F, the tortoise-shell glasses separating the outthrust ears: ‘I ain’t seen you since the night you played cowboy at old man Gold’s, misfit. How come you can’t get along with Sergeant Kvorka? Don’t you

like

him?’ As if every small-time hustler in the district, other than this strange exception before him, were half in love with good old Cousin Kvorka.

‘I got nuttin’ against Kvork. It’s just him don’t like me,’ the chinless wonder protested. ‘Fact is I respect Cousin for doin’ his legal duty – every time he picks me up I get more respect. After all, everybody got to get arrested now ’n then, I’m no better’n anybody else. Only that one overdoes it, Captain. He can’t get it t’rough his big muttonhead I’m unincapable, that’s all.’

The veteran edged restlessly half a foot toward the open door.

‘You’re unincapable all right,’ the captain agreed. ‘Your brains are screwed on sidewise – Hey,

you!

Where you think

you’re

goin’?’

The vet edged back.

‘Ever been in an institution?’ the captain wanted to know, returning to the 4-F.

‘Sure t’ing. The time my girl friend Violet hit Antek the Owner wit’ the potato-chip bowl I was in a institution: the Racine Street Station House Institution, it looks a little like this one. Only they wouldn’t let me stay. I ain’t smart enough to be runnin’ around loose but I ain’t goofy enough to lock up neither.’ The punk’s enthusiasm was growing by the moment. ‘Any time you want me, Captain, just phone by Antek, he’ll come ’n tell me I got to come down ’n get arrested. I

like

gettin’ locked up now ’n then, it’s how a guy stays out of trouble. I’ll grab a cab if you’re in a real big hurry to pinch me sometime – I don’t like bein’ late when I got a chance of doin’ thirty days for somethin’ I never done.’

The captain eyed him steadily. ‘You ain’t had enough dough your whole life to take you from here to Lake Street in a cab.’

‘Oh, I ride cabs all the time,’ the punk corrected him respectfully. ‘Every time I get drunk I hail a Checkerd, it seems.’

‘Good thing you don’t get drunk every half hour, you’d have traffic blocked. What’s your right name?’

‘Saltskin.’

‘Who’s “Sparrow”?’

‘That’s me too, Sparrow Saltskin, it’s my daytime name.’

‘What’s your nighttime name?’

‘Solly. Account I’m half Hebe.’

‘Half Hebe ’n half crazy,’ the wiser stray put in unexpectedly; but no one reacted to his comment and he shifted impatiently in the shifting light.

‘What were you here for the last time?’ the captain wanted to know of the Sparrow.

‘For nuttin’.’

‘For nuttin’?’

‘Yeh. For nuttin’. I jumped into the squadrol when that Kvorka stopped for the lights, so he had to bring me. I like ridin’ Checkerds best though. How many times I been pinched now, Captain?’ The punk bent curiously across the charge sheet. ‘You keepin’ tract for me? When I hit a hunnert I’m gonna volunteer fer Leavenswort’.’

‘I’ll keep tract for you all right, Solly,’ Record Head offered affably. ‘No trouble at all. When it’s a hundred we’ll hang you. You got ninety-nine now. Go on home – if you got one. Your roof is leakin’.’

‘Oney on one side,’ Sparrow protested with some dignity, putting on a dirty red baseball cap with the peak turned backward as if preparing to make a run for it.

‘I think you’re a moron,’ the captain decided at last.

‘He ain’t no moron,’ the veteran confided to Record Head, ‘he’s a moroff. You know; more off than on.’

The veteran’s flat, placid, deadpan phiz fixed absently upon an oversized roach twirling its feelers invitingly at him with a half-drugged motion from beneath the radiator: Come on down here where everything is warm love and cool dreams forever. Then, feeling the law’s eyes unwaveringly upon him, he recalled himself and advised the captain confidently: ‘We were pinched together, if the punk makes the street I do too. Otherwise it’s double jeopardy ’r somethin’.’

The punk turned upon the dealer leisurely. ‘Never saw this motherless lush in my life before, Captain. Ain’t them bloodstains on his jacket? You catch the guy sliced up the little girl yet?’

‘You’re both a couple loose bums livin’ off the weaker bums till Hawthorne opens,’ the captain concluded and called over their heads to someone unseen. ‘Throw these two in. It’ll give the suckers a chance to break even for a couple days.’

From out of the station-house shadows a hand snagged

Sparrow by the neck and immediately he sounded as if he weren’t so hot about sitting in the cooler overnight after all.

‘Why does everybody grab me by the neck?’ he demanded to know. ‘It ain’t no damned pipe. You tryin’ to get it offscrewed on me? Hey!’ He wailed over his shoulder to the captain as they took the first familiar steps down to the basement tier. ‘Bednar! Bednarski! Captain Bednarski! You got to book me fer

somethin

’!’

‘We’ll book you for killin’ that officer in Humboldt Park if you want,’ the turnkey offered, and a moment later the bars clanged shut. Behind his easy boasting the punk concealed a genuine terror of being caged – and every officer in the Saloon Street Station knew it.

‘Bring up a couple fuses while you’re down there,’ Record Head Bednar’s voice called from the top of the stairs, ‘we’re gonna fry the goofy one at 1:01.’

‘That’s you, Frankie,’ the punk assured the dealer swiftly.

‘No, that’s you,’ the dealer corrected him slowly.

It looked like a long night for Solly Saltskin. Not even Frankie Machine would guarantee him that the officers had only been joking.

‘There’s some things to kid about ’n some you ain’t s’pposed to, Frankie,’ the punk scolded him. ‘It’s a libel suit when you do. I could sue right now. I could sue you. You got me in here. Record Head was gettin’ me ready to make the street ’n you jammed the deal – false pertenses, that’s all you are.’ He threw a long looping left that Frankie caught in one hand, then scrubbed the punk’s wispy poll with it like a man fondling a mangy pup. If Sparrow had had a tail he would have wagged it then; if they’d been in the death house together he wouldn’t be too frightened so long as Frankie Machine was by.

To manhandle him fondly and get him into jams and then get him out again, just like that, the very next day.

‘If Schwiefka wasn’t always tryin’ to chisel on the aces we wouldn’t get tossed in the bucket so much,’ he confided in Frankie in the tone of one giving strictly inside information. ‘Bednar had Kvork pick us up just to show Schwiefka he’s a week behind wit’ the payoff.’ Then turned from the dealer, as the lockup went past rattling his keys, and in the same hoarse inside-info whisper: ‘Sssss – Pokey! You got this door locked

good?

We don’t want none of you crooked cops breakin’ in here tonight!’

The tranquil, square-faced, shagheaded little buffalo-eyed blond called Frankie Machine and the ruffled, jittery punk called Sparrow felt they were about as sharp as the next pair of hustlers. These walls, that had held them both before, had never held either long.

‘It’s all in the wrist ’n I got the touch,’ Frankie was fond of boasting of his nerveless hands and steady eye. ‘I never get nowheres but I pay my own fare all the way.’ Frankie was regular.

‘I’m a little offbalanced,’ Sparrow would tip the wink in that rasping whisper you could hear for half a city block, ‘but oney on one side. So don’t try offsteerin’ me, you might be tryin’ my good-balanced side. In which case I’d have to have the ward super deport you wit’ your top teet’ kicked out.’

For being regular got you in about as often as being offbalanced on one side. That was the way things were because that was how things had always been. Which was why they could never be any different. Neither God, war, nor the ward super work any deep change on West Division Street.

For here God and the ward super work hand in hand

and neither moves without the other’s assent. God loans the super cunning and the super forwards a percentage of the grift on Sunday mornings. The super puts in the fix for all right-thinking hustlers and the Lord, in turn, puts in the fix for the super. For the super’s God is a hustler’s God; and as wise, in his way, as the God of the priests and the businessmen.

The hustlers’ Lord, too, protects His own: the super has been in office fourteen years without having a single bookie door nailed shut in his territory without his personal consent. No man can manage that without the help of heaven and the city’s finest precinct captains.

What’re you gonna do for Dunovatka

After what Dunovatka done for you?

the captains still sing together at ward meetings—

Are you goin’ to carry the preesint?

Are you goin’ to be true blue?

Offhand it might appear to be a policeman’s God who protects the super’s boys. Yet a hundred patrolmen, wagon men, and soft-clothes aces have come and gone their appointed ways while the super’s hustlers linger on, year after year, hustling the same scarred doors. They are in the Chief Hustler’s hand; they have been chosen.

The hustlers’ God watched over Frankie Machine too; He marked Sparrow’s occasional fall. He saw that both boys worked for Zero Schwiefka by night while the super himself gave them hot tips each day.

The only thing neither the super’s God nor the super was wise to was the hypo Frankie kept, among other souvenirs, at

the bottom of a faded duffel bag in another veteran’s room. The barrel of a German Mauser and a rusting Kraut sword leaned out of the bag against the wall of Louie Fomorowski’s place above the Club Safari.

We all leave something of ourselves in other veterans’ rooms. We all keep certain souvenirs.

Sparrow himself had only the faintest sort of inkling that Frankie had brought home a duffel bag full of trouble. The little petit-larceny punk from Damen and Division and the dealer still got along like a couple playful pups. ‘He’s like me,’ Frankie explained, ‘never drinks. Unless he’s alone or with somebody.’

‘I don’t mind Frankie pertendin’ my neck is a pipe now ’n then,’ the child from nowhere admitted, ‘but I don’t like no copper john to pertend that way.’ For no matter how Frankie shoved him around the punk never forgot who protected him nightly at Zero Schwiefka’s.

Their friendship had kindled on a winter night two years before Pearl Harbor when Sparrow had first drifted, with that lost year’s first snow, out of a lightless, snow-banked alley onto a littered and lighted street. Frankie had found him huddled under a heap of

Racing Forms

in the woodshed behind Schwiefka’s after that night’s last deck had been boxed.

‘What you up to under there?’ Frankie wanted to know of the battered shoes protruding from the scattered forms. For this was the place where Schwiefka, urged by some inner insecurity, piled dated racing sheets. He never had it in him to throw a sheet away, pretending to himself that he was filing them here against a day when age would lend them value; as age had in no wise increased his own. Frankie used them, on the sly, for starting Schwiefka’s furnace; but advised the shoes severely: ‘Don’t you know this is Schwiefka’s filin’ cab’net?’

Sparrow sat up, groping blindly for his glasses gone astray

somewhere among the frayed papers below his head. ‘I’m a lost-dog finder,’ he explained quickly, experience having taught him to assure all strangers, the moment one started questioning, that he was regularly employed.

‘I know that racket,’ Frankie warned him, trying to sound like a private eye, ‘but there ain’t no strays to steal in here. You tryin’ to steal wood?’ Frankie had been stealing an armload of Schwiefka’s kindling every weekday morning for almost two months and didn’t need help from any punk.

‘I got no place to sleep, Dealer,’ Sparrow had confessed, ‘my landlady got me locked out since the week before Christmas. I been steerin’ for Schwiefka all day ’n he told me I could sleep in here – but he ain’t paid me a cryin’ dime so it’s like I paid my way in, Dealer. It’s too cold to steal hounds, they’re all inside the houses. Some nights it gets so cold I wisht I was inside one too.’

Frankie studied the shivering punk. ‘Don’t shake,’ he commanded. ‘When you get the shakes in my business you’re through. Steady hand ’n steady eye is what does it.’ He handed him a half dollar.