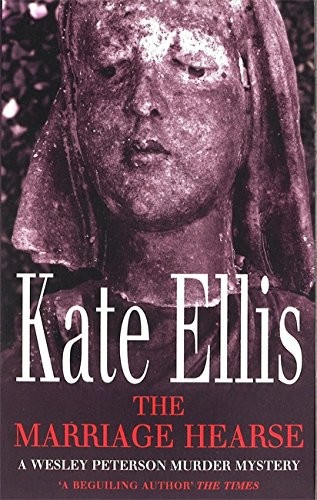

The Marriage Hearse

Read The Marriage Hearse Online

Authors: Kate Ellis

Kate Ellis was born and brought up in Liverpool and studied drama in Manchester. She has worked in teaching, marketing and

accountancy and first enjoyed literary success as a winner of the North West Playwrights competition. Keenly interested in

medieval history and archaeology, Kate lives in North Cheshire with her husband, Roger, and their two sons.

The Marriage Hearse

is her tenth Wesley Peterson crime novel.

Kate Ellis has been twice nominated for the CWA Short Story Dagger, and her novel

The Plague Maiden

, was nominated for the

Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year

in 2005.

The Merchant’s House

The Armada Boy

An Unhallowed Grave

The Funeral Boat

The Bone Garden

A Painted Doom

The Skeleton Room

The Plague Maiden

A Cursed Inheritance

For more information regarding Kate Ellis

log on to Kate’s website:

www.kateellis.co.uk

Published by Hachette Digital

978-0-748-12667-5

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public

domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely

coincidental.

Copyright © 2006 Kate Ellis

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

The young woman was virtually naked, her modesty only partially redeemed by a white lace bra and a frilly blue garter that

dug into the pale flesh of her right thigh. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.

A pair of pants, snowy lace to match the bra, lay in a small, frothy heap on the pink carpet beside the bed where the woman

lay, quite still, her legs apart, one clenched hand half concealing the small triangle of dark hair between her legs.

But there was no hint of invitation in the wide blue eyes that bulged in pain and astonishment from her twisted face. Her

small, pink tongue protruded from her blue-tinged lips. She had been attractive once, perhaps on the verge of beautiful. But

death changes everything.

A dark figure leaned over her and began to wind the flex from the bedside lamp around her pale neck, carefully, almost lovingly.

Once the flex had been pulled tight enough to mark the tender flesh, the figure brushed a hand against the still-warm cheek

and planted a chaste kiss on her forehead.

‘I’m sorry,’ a voice whispered, breaking the heavy silence of the small, neat bedroom. ‘I’m so sorry.’

LOST PLAY PREMIERE FOR FESTIVAL

One of the highlights of this year’s Neston Arts Festival will be a newly discovered play dating from the time of Queen Elizabeth

I

. The Fair Wife of Padua

was penned by Ralph Strong, a Devon man who worked in Elizabethan London alongside the likes of William Shakespeare

.The Fair Wife of Padua

was lost for centuries until a manuscript was discovered by chance by a librarian cataloguing the library of ancient Talford

Hall near Exeter. Lord Talford is said to be thrilled by the discovery and he and Lady Talford are looking forward to attending

the play’s premiere at Tradington Hall on Saturday 13th August

.The play will be performed by the Tradmouth Players (renowned for their annual outdoor Shakespeare performances in Tradmouth

Memorial Park). A spokesperson for the Tradmouth Players described the play as ‘perhaps not as accomplished as Shakespeare

but nevertheless a challenging and powerful tragedy’

.Tickets for

The Fair Wife of Padua

are available from Neston Arts Festival Box Office

.Neston Echo,

26th July

The bride carried a small bouquet of sad flowers. Yesterday’s rusty rosebuds, slightly past their best, pulled from the reduced

bucket that stood at the entrance to Huntings Supermarket. She held the blooms in front of her like a defensive shield as

she gave her bridegroom a shy half-smile. It was two o’clock. Time to go in.

Morbay’s registry office was tucked away at the rear of the Town

Hall. But despite this handicap, the staff did their best to make the place as welcoming and attractive as possible to those

couples who chose to marry there and to those joyous or grieving souls who entered its portals to register the birth or the

death of a loved one.

Joyce Barnes, the motherly registrar, was adept at fitting her manner to the occasion; cooing with proud new fathers or giving

unobtrusive sympathy to bereaved relatives. Over the years she had perfected the knack of joyful solemnity, so appropriate

when she was pronouncing that a couple were bound together till death – or in some cases boredom – did them part.

Joyce gave the young bride what she considered to be an encouraging smile. ‘Are you ready?’ She studied the girl. Thin with

a slightly olive complexion and brown eyes. Straight brown hair scraped back into a ponytail. She wore a cream silk skirt,

cut on the bias, which clung flatteringly to her slim hips and a little silk top, red to match her bouquet. In Joyce’s opinion

she looked as though she could do with a good meal.

‘Are your witnesses here?’ Joyce asked, trying to sound cheerful even though she had a headache coming on.

Two girls stepped forward. They were around the same age as the bride and one sported a dark ponytail, the other a fair. They

were wearing jeans. But then Joyce had seen some sights at weddings over the years and she was hardly fazed by a glimpse of

denim.

The girl glanced at her bridegroom and smiled nervously as he took hold of her hand, raised it to his lips and kissed it,

his eyes aglow with desire. He was a swarthy man, rather stocky and probably ten years her senior. But then, thought Joyce,

love is frequently short sighted, if not blind. She thought of her own ex-husband and suppressed a shudder before forcing

herself to smile.

‘If you’d like to come through …’

She began to lead the way into the thickly carpeted marriage room, glancing back after a few seconds to make sure they were

following.

She caught the young bride’s eye and was about to smile but

something stopped her. What she saw wasn’t pre-nuptial nerves.

It was fear.

The joyous clamour of the bells fell silent.

The tower captain glanced at the small electric clock on the wall. ‘Twenty minutes late.’

‘Probably the traffic,’ said the girl who’d been ringing the treble, a rosy-cheeked student in shorts and T-shirt. ‘Tourists,’

she added in a tone usually reserved for the mention of vermin.

The other ringers nodded in agreement, apart from the tall elderly man tying up the rope of the third bell. ‘She’ll be exercising

her prerogative. Keeping him waiting. Starting as she means to go on.’

All eyes focused on the red light bulb fixed to the tower wall. When the wedding car pulled up, the bulb would flash once

and when the bride finally reached the church porch after her customary photo-call, the bulb would light up, a signal to the

ringers to stop. There was a similar bulb next to the organ to cue the wedding march. An ingenious system that had never let

them down yet.

But today there was no flash of light. The ringers resumed their places and embarked on ten more minutes of fast Devon call

changes, their eyes on the naked bulb, before deciding to take another break. Half an hour late now. This was getting ridiculous.

The bells were rung from a wide balcony at the back of the church and the ringers drifted over to the wooden rail where they

customarily congregated to watch the bride’s progress down the aisle.

From their lofty vantage point they could see the congregation and they sensed an uneasy atmosphere down in the nave. Men

in dark morning dress darted in and out of the church while women in large hats held hushed conversations. By tradition brides

were supposed to be late. But not this late.

With each minute that passed the volume of anxious chatter increased and the bellringers, in common with those down below,

began to speculate amongst themselves, the breakdown of the wedding car being the favourite explanation. They saw the vicar

in his snowy white surplice speaking to the anxious bridegroom in the front pew before hurrying outside. In this age of mobile

phones, surely someone would have heard something by now.

The hum of conversation grew louder still, filling the nave, drifting up to the bell tower. Where was she?

‘She’s stood him up. Jilted the poor sod at the altar,’ the elderly pessimist on the third bell said with inappropriate relish.

The tower captain, an amiable man, gazed down at the bridegroom’s anxious face and felt a wave of sympathy for the young man’s

public humiliation.

‘She’s here,’ the boy ringing the fourth bell hissed. At the age of sixteen the comings and going down in the church didn’t

interest him. He had been texting his friends on his mobile phone whilst keeping an eye on the bulb.

Sure enough the light was flashing. The wedding car had arrived. The ringers rushed to their ropes and the happy clamour of

the bells began again. First an octave. Then the bells began to swap their places, creating elaborate and rapidly changing

music. The light had gone out now. Soon it would come on again and the bells would fall silent until it was time to ring the

happy couple out of church.

Five full minutes passed and there had been no signal for the ringers to stop. But then some photographers took their time.

Suddenly a figure in white appeared at the church door. But it wasn’t the bride who was entering to the accompaniment of the

bells but the vicar, in his snowy surplice, supporting the arm of a middle-aged man. The confused and impatient organist,

spotting the flash of white out of the corner of his eye, embarked on the first few notes of Wagner’s wedding march. But he

stopped suddenly as he realised his mistake, as did the bells.

The vicar was shouting to make himself heard over the din of voices, clapping his hands like a schoolteacher trying to calm

an unruly class. ‘Please, ladies and gentlemen. If I can just have your attention …’

The bellringers, sensing excitement, rushed over to their rail and leaned over to get a better view as the congregation fell

silent

The vicar’s voice was shaking as he began to speak. ‘I’m afraid there’s been a tragic accident.’

But he was interrupted by the middle-aged man next to him – the man most of the congregation recognised as the bride’s father.

‘Kirsten’s dead,’ he shouted, his voice unsteady as tears streamed down his face. ‘Some bastard’s killed my little girl.’

He sank to his knees and let out a primitive wail of grief as the bride’s mother issued a piercing scream.

Detective Inspector Wesley Peterson stood at the bedroom door and watched the forensic team going about their work. He avoided

looking at the contorted face of the young woman lying on the bed. She was only wearing a bra and a ridiculous pale blue

garter and Wesley fought a strong urge to cover her up; to at least give her some dignity in death. But his training had taught

him that contaminating a crime scene is a cardinal sin. She would lie there to be examined and photographed, her nakedness

exposed to a group of complete strangers until they were satisfied that her silent corpse could safely be taken to the mortuary

in a discreet black van.

All he had learned about her so far was that she had been identified as Kirsten Harbourn, aged twenty-three. And that her

father had found her body.

He looked around the room where she’d died. A feminine room – pink and frills. An ivory silk wedding dress with a full skirt

hung against the wardrobe door like a hooked parachute and an elaborate tiara sat in the middle of the white dressing table

next to a wispy veil. A CD player stood on a matching chest of drawers, a glowing red LED suggested that the victim hadn’t

switched it off before her death. Perhaps she had died to a musical accompaniment. Wesley found the thought macabre.

He turned and made his way down the hallway, careful to walk only on the metal plates placed there to protect any footprints

the young bride’s killer may have left, invisible to the naked eye but potentially detectable with the SOCO’s box of magic

tricks. Detective Chief Inspector Gerry Heffernan hovered in the open doorway, his large frame blocking the light from outside.

‘So what do you think?’ Heffernan asked anxiously. Wesley had noticed that his Liverpool accent seemed to deepen in times

of stress. And he certainly looked more stressed than normal.

Wesley thought for a few moments. ‘Looks sexual.’

‘That’s all we need, some sex maniac on the loose.’ He scratched his head. ‘When we get back to the station we’ll draw up

a list of all the sex offenders on our patch – especially any who’ve attacked women in their own homes. But there’s so many

ruddy tourists around at this time of year it could be someone from London … or Manchester … or Aberdeen … or Timbuk ruddy

tu.’

‘Perhaps there’ll be DNA,’ said Wesley optimistically. ‘Has Colin arrived yet?’

Heffernan shook his head. Dr Colin Bowman, the pathologist, was in the middle of a postmortem but he’d promised to be there

as soon as possible.

‘Her father found her, is that right?’ Wesley asked. He had only just arrived at the murder scene, having been enjoying a

quiet Saturday at home with his wife, Pam, and the children. His sister, Maritia, who was staying with them for a couple of

weeks while she helped to decorate the house she would be moving into when she married in a month’s time, had left first thing

that morning armed with a wallpaper scraper and a pot of white gloss paint, so he and Pam had been experiencing a rare interlude

of domestic peace. Pam had said nothing when he’d been called out. But the expression on her face had said it all.

‘It doesn’t bear thinking about, does it? Finding your own daughter dead like that.’ Heffernan shuddered. His own daughter,

Rosie, was around the dead woman’s age. Somehow it made it personal.

‘I expect he’s in a hell of a state. Have the rest of the family been told?’

‘The rest of the family and all their friends and acquaintances.’ He hesitated. ‘She was getting married today. Everyone was

dressed up in their finery waiting for her in Stoke Raphael church, looking forward to cracking open the champagne. When she

didn’t turn up, everyone assumed she’d changed her mind.’

Wesley shook his head, lost for words. The thought of all that joy and anticipation turned suddenly to grief was almost too

much to bear.

‘As soon as he found her, her dad called the police on his mobile then he got the wedding car to rush him over to the church.

Well, he had to break the news, I suppose. Couldn’t leave them all sitting there.’

‘No, don’t suppose he could,’ Wesley said quietly. He stepped outside into the sunshine. He needed some fresh air. He noticed

the house name on a rustic wooden plaque to the right of the front door. Honey Cottage. A pretty name for a pretty place.

But now it would always hold sinister connotations. The papers would call it ‘the Honey Cottage murder’. They would love the

juxtaposition of the sweet and the horrific.

He turned to his boss. ‘If she was getting ready for her wedding, why wasn’t anyone with her?’

Heffernan shrugged. ‘She went to the hairdresser’s in Neston at nine this morning with her mum and her bridesmaid, Marion

Blunning. Marion’s dad’s just had a suspected heart attack so she went off to see him in hospital.’

‘And her mum?’

‘She dropped her off here at eleven o’clock. Kirsten asked her to go to the hotel where they were holding the reception to

check that everything was in order before going on to the church. She said she’d be fine getting ready by herself. Her dad

was picking her up in the wedding car at twelve thirty and when he arrived he found her … Well you’ve seen how he found her.’

‘So she must have died between eleven when her mum left and twelve thirty when her father found her. How did her killer get

in?’

‘The door was unlocked. He probably just walked in on her while she was getting dressed.’

‘Lucky timing.’

‘Maybe he’d been watching the house. She didn’t draw the curtains.’

‘She probably didn’t think she needed to.’ Wesley looked round. ‘It’s hardly overlooked, is it?’

The cottage where Kirsten Harbourn had encountered death stood on the edge of the hamlet of Lower Weekbury, three miles out

of Neston. A small whitewashed building with a fringe of neat

brown thatch. A cottage from a picture postcard, adjacent to the grounds of Tradington Hall. Lower Weekbury had no church,

no village shop, and its one and only pub had shut in the 1960s. Once, its small dwellings had housed farm workers but now

a few were occupied by commuters who worked in nearby towns and the remainder were second homes or holiday lets.