The Mascot (31 page)

Authors: Mark Kurzem

Alice placed her hand on top of the pile of books.

“I haven't had a chance to look at these yet,” she said. “The target is Koidanov. We've all got to put our minds to it.”

“I'm not clever enough for that,” my mother said from where she was preparing coffee. “I'll make the drinks and sandwiches instead.” After she brought our coffees to the table, she retreated to her territory on the other side of the kitchen counter, near the stove and the sink.

In the end, the discovery of Koidanov was surprisingly easy, if not quite straightforward. Once we had finished our coffee, Alice reached for one of her many books, all of which were written in either Yiddish or Russian. She popped her reading glasses on the end of her nose, put a pen behind her ear, and got down to business. Hunched over the table and squinting at the pages of the book in front of her, she reminded me of a Damon Runyon character, perhaps a bookie taking bets on my father's past and future.

“Let me see⦔ she said, going through various possible spellings, “Koidanovâ¦Kuidnovâ¦Koydanev.” Within about ten minutes she had found mention of Koidanov in a list of the various

samulbuch

that had been published. “A

samulbuch,

” she explained, “is a collection of historical informationâphotos, anecdotes, essays, and memoirsâthat were kept by the Jewish communities of many towns and villages in eastern Europe.

“Here,” she said, pointing at a word on the list. “There's one for a village called Koidanov in the Minsk region in Belarus. Aahâ¦I know why you couldn't find it on any map. It states that just before the Second World War the name of the village was changed to Dzerzhinsk. Named after the ignominious founder of the Cheka. Stalin must have been keen to give the place a more Soviet flavor.”

In the atlas I'd scoured with my father nights earlier I had in fact come across the name Dzerzhinsk.

Alice shifted her attention to another book among the stack on the table. This one contained maps of prewar Europe, and she consulted one in particular. She had no difficulty in pinpointing Koidanov, and we gathered around her, staring at the spot where she had placed her finger. I was unsure. Koidanov lay some distance to the northeast of Stolbtsiâthe town that my father thought might have been referred to as “S” by the soldiers and the site of their base camp, not far from where they claimed to have “discovered” him.

But it was possible, especially if my father had wandered for months on end in a wide circle before being picked up by the Latvian police brigade in the vicinity of Stolbtsi. Taken there by Kulis, who received permission there from Lobe to adopt the boy as the troop's mascot, he was tidied up, given a uniform, and could easily have been dispatched to Slonim, where the massacre had occurred. Of course, it was feasible only if my father had been picked up by the soldiers earlier than they claimed. Professor M. at Oxford had conjectured that any extermination in my father's village would have to have occurred before December 1941 if my father was also to have witnessed the Slonim massacre, which has been variously dated from late 1941 onward. That is, of course, assuming that the Soviet accusation against Commander Lobe and the Latvian police battalion was justified. Or perhaps my father had been picked up in June 1942, as Lobe and others claimed, and was not a witness to the massacre at Slonim but to another unnamed incident.

I scanned the map further to reconfirm what my father and I had already discovered: that to the west of Stolbtsi lay Slonim. Was this distance also too far for the Eighteenth to have ventured on duty?

I cast a quick glance at my father, who was already staring at me. He must have had a similar train of thought. I was on the verge of commenting on this when my father indicated with his eyes and an almost imperceptible shake of his head that I should say nothing.

Fortunately, Alice hadn't noticed our exchange. She continued to stare at the name on the map as if it would somehow magically transform into a window through which we could see Koidanov, past and present. We were all buoyed by the discovery that Koidanov was an actual place. Alice rifled enthusiastically through her books, trying to learn more about Koidanov, while we hovered expectantly around her.

My mother placed another cup of strong black coffee on the table for Alice, who sipped it gratefully. Then she reached across for another of her tomes, this one written in Russian. In it she found a brief reference to Dzerzhinsk and a massacre that had occurred there on October 21, 1941. It spoke of the killing of sixteen hundred patriots by Fascists during the Great Patriotic War.

Alice grunted in annoyance. “In other words,” she said, “translating from Sovietspeak, sixteen hundred Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.”

“What do you mean?” my father asked.

“The Soviets didn't acknowledge the Holocaust,” Alice explained. “Exterminations of this sort were just called crimes against patriotic citizens. And the Second World War was referred to as the Great Patriotic War.”

She leaned back in her chair and took another sip of coffee. “The next thing we need to do is to establish contact with Koidanov. I have one contact in Minsk: Mrs. Reizman, a historian who works at a Holocaust research center there. We've exchanged letters a couple of times.” She plucked her address book out of her bag.

“Here it is,” she said. “If anyone has access to information about Koidanov, then Frida Reizman will be the one.”

Alice rolled another cigarette and took a long drag.

“Why don't we write to her now?” she suggested.

“This minute?” My father seemed shaken by the immediacy of it.

“What do they say in English?” Alice asked, looking at me cheekily. “Strike something while it's hot⦔

“Strike while the iron is hot,” I corrected her.

“Okayâ¦Okay,” she said. “We need to get all the details of your story written down and then send it off to her.”

My father's face started to brighten at the possibility opening before him. He nodded in agreement.

I felt my mother looking at me from across the kitchen. She gave a smile when our eyes met, excited in her own cautious way. She reached into one of the drawers under the kitchen counter and pulled out a pad of paper and envelopes.

I sat alone in the living room, listening to the soft murmur of my father's and Alice's voices as they composed the letter. I began to plan the logistics of the journey to Minsk. My thoughts were interrupted when I heard Alice call my name. I went to the kitchen, where my father sat anxiously by her side.

“It's finished,” she said, looking up at me. “Tell me what you think. You're the young man with the good education.”

I laughed, and returned to the living room to proofread the letter. It was fine, describing as much as it could of the details we had to go onâthe words “Koidanov” and “Panok” and a description of the massacre my father had witnessed in his village.

I heard the sound of Alice's walking stick on the polished kitchen floor as she hobbled around, stretching her legs. Her face appeared around the doorway, followed by my father's.

“You approve?” she asked.

“Of course,” I replied.

“It's great, Alice,” my father added.

Alice smiled shyly, pleased with our praise.

“You must post it yourself,” she said to my father. “It will be symbolic.”

“Do you think something will come of it?” my father asked. His words had a hopeful tone, but Alice only shrugged.

“Time will tell,” she said.

“I'll take it to the post office straight away,” my father said, already heading for the front door. “Be back soon.”

“I'll come with you,” I called after him, grabbing my jacket.

I tried to keep up with my father's stride; shamefully, he was in better shape.

“Why didn't you want me to mention Slonim to Alice?” I asked, already slightly breathless.

“I don't want Alice to think that I was associated with something like that,” my father answered, maintaining his speedy pace.

“You mean suspect that you might've killed people yourself?”

My father nodded.

“You didn't, did you, Dad?”

It was a question I had always dreaded asking him. I was relieved that we were both facing ahead, and I didn't have to look him in the face.

“Never,” he said. I saw him shake his head.

“Never,” he repeated. “Not once did I lay a hand on another person, even though the soldiers tried to get me to do so. Much to their amusement I would always run away, petrified.”

We continued to walk side by side.

“There was one incident, the worst of all,” my father said quietly, as if he feared the neighborhood would hear him. “We were on patrol in a forest. I'm not sure where. The soldiers had captured a Jewish ladâhe must have been with the partisans. He was no more than sixteen or seventeen, a teenager, really. They bound his hands together and led him back to our camp.

“When we got there, they tied him to a tree with a long piece of rope. Then they started firing their pistols on the ground around his feet to make him jump and dance around the tree. They were laughing, as if it were a game.

“I couldn't bear to look. I'd caught a glimpse of the terror in the boy's face. Just as I was trying to slip away, one of the soldiers thrust a pistol into my hand. âShoot!' he shouted at me. âShoot!'

“They all began clapping their hands together, chanting âShoot' over and over.

“I was almost as terrified as the boy. I was trapped. There was no way out.

The only thing that came into my head was to aim badly at the boy's feet, so that's what I did. The bullet struck halfway up the tree instead.

The soldiers let out a groan of disappointment, and one of them demonstrated how I should aim the pistol. I nodded my head confidently, as if I'd now grasped what I should do.

“I took aim againâmind you, I was already an excellent shot from target practice with the soldiersâand this time I deliberately fired just over the head of one of the soldiers standing on the opposite side of the tree.

“He ducked, but I knew I wouldn't have hit him anyway. A few of the soldiers began to hurl abuse at me, but I believe that Sergeant Kulis realized that I'd misaimed deliberately. He gave me a furtive warning glance and then strode quickly over to me and gave me a clip around the ear. âHe's a fool,' he called to the other soldiers. âHe needs more pistol training.' With that, he began to push me toward the barracks and out of harm's way.

“He'd defused the episode, but I knew that he viewed what had gone on as a test of my willingness and loyalty to the squad. And I'd failed. I wasn't capable of killing anybody, Jewish or not. I must have had something in me that resisted that.”

We reached the post office and stood outside the entrance.

“The soldiers killed everything they could lay their hands on. Incidents like that made me feel that I was a killer just because of what I witnessed. Just because I was with them. Perhaps those interviewers are right. I am a killer of Jews, not literally, but because I stood by and did nothing.”

“Dad, you were only five or six then,” I tried to reassure my father. “What could you have done to stop them? You would have been powerless against grown men. They would have turned their guns on you and killed you.”

My father nodded. “Perhaps that would have been a better solution to my fate,” he said. “To have died as a child, a forgotten, unknown martyr, rather than face their hate and accusations now.”

My father was quiet.

“What happened to the boy?” I asked.

My father shook his head. “When I returned later in the day, the rope was still tied around the tree, but there was no sign of the boy.”

NIGHTMARES

A

fter his initial enthusiasm at sending the letter, my father's spirits began to flag. One morning I found him alone in the kitchen, staring bleakly into space.

“Even if Koidanov turns out to be my village,” he said, “what will be there for me but a handful of memories? And they are here with me.” He tapped his chest.

“So what do you hope for from the letter?” I asked.

“To be honest, son,” my father replied, “I don't know. Are we clutching at straws? Who would remain there to miss me, or remember me? My entire family perishedâ¦though I still cannot place my father at the extermination.”

I had no answer for that. I also suspected that working from the scant, nonspecific clues that we had provided would stymie Frida's efforts, no matter how enterprising.

The question of Panok remained especially oblique and intriguing for us all. Frank had finally contacted me with the news that his search had failed to establish any definite connect between Panok and the village of Koidanov. Yet why were the two words so strongly associated in my father's memory? Frank also told me that the Panoks who had lived near Minsk in prewar times had all perished in the Holocaust. It seemed that there would be no Panoks to find.

Yet my father would not let go of the mystery of the Panoks. On several occasions he insisted that Panok must be his name, only to retreat moments later into a state of stoic resignation, claiming to have no interest whatsoever in who he might have been.

I began to worry about his mental and emotional fragility.

Despite the somber mood that had descended over the household as we waited for a reply, by day, at least, we maintained a semblance of normality. My parents tried to return to the routine of their daily lives. My father spent his days in his workshop tinkering. On Sundays he and my mother went out for lunch or visited friends. Often they were drawn to the secular synagogue of Café Scheherazade. My mother would browse through her women's magazine over coffee and cheesecake, while my father sat on the edge of his chair, restlessly observing the comings and goings of other customers. He seemed eager, almost desperate, my mother said, to talk to the ones with sympathetic faces and tell them his story.

I was somewhat buoyed by the hours I spent in research at the library trying to get a picture of the historical context of my father's fate. At times, rather frustratingly, the research itself threw up different versions of the same event. In the end, I could construct only the very broadest of canvases based on indisputable historical evidence.

For example, records revealed that in July 1941 Heinrich Himmler had visited Minsk. The purpose of the visit was ostensibly to facilitate “living space” for western European Jews deported to the east. Himmler was keen to see the eradication of Jews in Belarus for that reason, and during that period he ordered

Aktionen

to begin in the region. (This was prior to the Wannsee Conference of January 1942, and the Final Solution, the systemized efficiency of the gas chambers and death camps, had yet to be implemented. In the pre-Wannsee period shooting the Jews one by one and leaving them in mass graves had been the predominant means of clearing the Jewish population out of the villages and towns of eastern Europe.) The killings were carried out by Einsatzgruppen, composed variously of Baltic police battalions and other military units. These groups were ultimately under the command of the German SS but had an internal hierarchy of local commanders. I learned that Einsatzgruppen had entered parts of White Russia, especially the area surrounding Minsk, and begun their

Aktionen

in the late summer and early autumn of 1941.

During subsequent days I learned also about the Latvians in the region. A police battalion, commanded jointly by Commander Lobe and Captain Rubenis, had been dispatched to the region in November/ December 1941 to assist in “mopping up duties” and hunting “partisans,” an umbrella term used along with “Bolsheviks” as a euphemism for the Jewish population. These facts coincided exactly with my father's confused memory of the presence of both Lobe and Rubenis when he was with the soldiers. It also accounted for the fact that my father had initially insisted to me that his battalion had hunted for only “partisans” and not Jews. As a boy of five, he would have accepted at face value what the soldiers had told him. What was most significant was that different versions contradicted each other as to whether the Latvian police brigade could have been present in time for the Slonim massacre.

In mid-1942 the brigade was incorporated into the Wehrmacht as the Eighteenth Battalion. It was eventually recalled to Riga in the late spring of 1943, where after a brief period it was again transformed, this time into an SS unit, the Kurzeme Battalion, under the command of K rlis Lobe. In July 1943, the Kurzeme Battalion was sent to the Russian front south of Leningrad to a place called the Volhov swamps, north of Velikiye Luki, exactly as my father had remembered. Crucially, the transformations of the Kurzeme Battalion had involved at least two changes of uniform, which again resonated with my father's memories.

rlis Lobe. In July 1943, the Kurzeme Battalion was sent to the Russian front south of Leningrad to a place called the Volhov swamps, north of Velikiye Luki, exactly as my father had remembered. Crucially, the transformations of the Kurzeme Battalion had involved at least two changes of uniform, which again resonated with my father's memories.

I verified in a number of sources that there had been an extermination in the town of Koidanov, and that it had indeed occurred on October 21, 1941. This date seemed familiar; but later, going through my father's documents, I noted that it was two years later almost to the day that my father became Dzenis's ward.

Each night after dinner, my mother would wash the dishes or do the ironing while my father sat at the kitchen table in silence as I, much like a private detective reporting to a client, related the grisly details that had come to light that day.

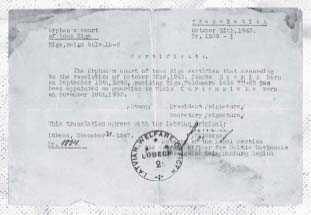

The certificate from the Orphan's Court of Riga that gave Jekabs Dzenis guardianship of Alex.

On one such occasion, after learning of the Koidanov massacre and recounting it to my father, something very sinister occurred to me.

“Perhaps⦔ I began, and then stopped myself.

“Perhaps what?” My father was suddenly alert.

I didn't want to let my father into my train of thought: what if the Latvian police brigade had committed the Koidanov massacre? In other words, what if my father had been adopted and cared for by the very men who had murdered his mother, brother, sister, and extended family?

The thought sent a shiver through me. I didn't want my father to have to even contemplate the terrible possibility that Lobe and Kulis may have murdered his family.

In the end, I was glad that I'd held this suspicion back from him. I learned later that the Koidanov extermination had been perpetrated by the Lithuania Second Brigade, which was also operating in a number of villages southwest of Minsk during 1941.

*

During my research, I came across a controversy about the actions of the Latvian police brigade that directly touched upon my father's memories. It pertained to the massacre in Slonim, which may have been within striking distance from “S,” where the brigade had set up temporary camp.

According to what Uncle told my father and to the records, in the postwar period the Kurzeme Battalion had been held responsible by the Soviet authorities for a massacre that had taken place there in late 1941 (though again I found a number of conflicting dates for the incident). A war crimes trial had resulted in the execution of several members of the battalion who had not managed to escape from Latvia. Others, including Lobe, claimed that the battalion hadn't been involved and had never been in the vicinity of Slonim. Judging by what I read, their involvement was still a matter of controversy among historians and Latvian patriots alike. What attracted my attention above all, and most troubled me, were several eyewitness accounts of the massacre. Witnesses stated that they saw Jewsâthe elderly, women, and childrenâherded into a synagogue and burned alive. This account perfectly reflected the memory my father had recounted to me. It had taken place on the day he'd been tied to the soldier on the roof of a train and transported with the brigade to an unidentified location. It was also the day when soldiers had jostled for a chance to be photographed with the unusual boy soldier in his uniform.

Had my father in fact been taken to Slonim, where he witnessed the massacre?

When I put the question to him, my father had prevaricated.

“It could've been another time and place.”

And that may have been the case. Certainly many synagogues would have been set alight as the troops went about their dirty business.

But then my father had a change of heart.

“The soldiers claim to have picked me up in late May 1942, but what if it had been sooner, much sooner, even before Slonim? The key question is how long I was in the freezing Russian forest, and you know I still find it hard to believe that I was alone there throughout the entire winter. How could a child survive such deprivation?

“It was Commander Lobe who told me about how they rescued me, even that it was the summer season. Perhaps with time I've grown confused. I remember clearly that Kulis rescued me from the firing squad, but in my mind I've pictured that it was summer because that was what Lobe insisted. But, you know, I am sometimes troubled by a sense that there was snow on the ground when I was dumped in the firing line. That's my problem: my memories blend together between what I actually remember and what I was instructed to remember.”

My father paused. “Why would they have lied about such a thing?” he asked.

“To cover their tracks,” I reminded him. “You could have been a witness against any of the men who were there. I wonder what happened to the photographs that were taken that day. I wonder if any of the soldiers kept them.”

My father shrugged. “Who would be crazy enough to keep something that implicated them as a war criminal?”

The fragile silence of our household was disturbed almost nightly by the wails and shouts that emanated from the spare room where my father had taken to sleeping to avoid disturbing my mother. I would lie half-awake in fear and anticipation of what that night's dreams would bring to my father. My mother and I often found ourselves together outside his room, our ears pressed against the closed door, eavesdropping on the tormented man.

Sometimes we would hear my father stir and begin to move about the room. At that point my mother would tap lightly on the door.

“Alex?” she would whisper, as if unsure it was her husband on the other side. “Alex? Are you okay?”

We would hear his muffled and drowsy-sounding answer: “I'm fine. Just a bad dream. Go back to bed.”

“I'll talk to him,” I would say to my mother. “You get some sleep.”

“Tea?” I would say to my father through the closed door.

His usual response would be, “Okay, son, I'll join you shortly,” though on a few occasions he ordered me to go back to bed. He needed his privacy, and I wondered what he had seen in his dreams that he couldn't share.

On most occasions, however, I would prepare tea in the kitchen. My father would enter some minutes later, after what I imagined to be a process of recovering himself, literally, from his dreams.

Sometimes he sat silently, as if in shock, sipping from his cup. I would sit opposite him, waiting for him to speak. These moments were both ghoulish and titillating because I didn't know if my father would be able to recall what he had just dreamed and if it might somehow be another clue to unlocking his past.

But that past was beginning to overwhelm him.