The Miseducation of Cameron Post (25 page)

Read The Miseducation of Cameron Post Online

Authors: Emily M. Danforth

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Homosexuality, #Dating & Sex, #Religious, #Christian, #General

At the sermon he wore a nice button-down shirt and a silvery-blue tie and read from one of his books, talked in generalities about the importance of Christian faith starting and staying in the family. But at the Firepower meeting we got jeans-and-T-shirt Rick, guitar in tow, and more than a few of the female members expressed their megacrushes in barely whispered whispers.

Coley and I sat next to each other, Indian style (though we were being told to now call it crisscross applesauce), on the gray carpet of the meeting room. We were careful not to let our knees touch, our shoulders brush, lest we call up our movie-night activities.

Rick lead us in the acoustic versions of a couple of songs by popular Christian rock acts, Jars of Clay for one, and everybody, including me, was impressed at the up-to-dateness of his repertoire. He tucked stray curls behind his ear and smiled at compliments in that shy kind of artsy-poet way that made husky Mary Tressler and birdlike Lydia Dixon giggle and wink at each other.

“We’ll do this up casual, you cool with that?” Reverend Rick asked, removing the guitar strap and setting his shiny acoustic at his side, then turning back to us and tucking some more of that hair, despite its not needing to be tucked. “So ask me anything. What’s on the minds of teenagers in Miles City, Montana?”

Nobody spoke. Lydia Dixon giggled again.

“You can’t always be this quiet,” Reverend Rick said, doing a semiconvincing job of appearing unaware of his celebrity status.

“You could tell us about what you’re doing with your school in Montana or whatever,” licorice-smelling Clay Harbough said to his lap, no doubt as anxious as I was to get this meeting over and done with, though in his case it was probably to get back to whatever he was doing with his computer that month, and in my case it was to avoid the topic that he’d just suggested.

“You bet,” Rick said, smiling that shy smile. “It’s a big summer for Promise—we’re celebrating our third-year anniversary here in a couple of weeks.”

“My parents just sent in a donation card,” Mary Tressler said, all puffed up, seriously almost batting her eyes at the poor guy.

“Well, we certainly appreciate any and all of those,” Rick said, smiling back at her, not smarmy like a televangelist either, but with a genuine sort of smile.

“But it’s for like curing gays or whatever, right?” Clay asked, talking more during this meeting than I could remember him talking ever.

Coley had to have known that this was what we were getting to—I knew it, this is what this guy did, what he was known for—but I could feel her, next to me, tense just a little at those words:

curing gays

. Maybe I tensed too. I tried to seem cool, though, cool like Rick. I made a point of keeping eye contact with him.

“We don’t really use the word

cure

so much,” Rick said, without seeming at all like he was necessarily correcting Clay, which was a real kind of conversational gift. “We help teens come to Christ, or in some cases come back to Christ, and develop the kind of relationship with him that you all are working on. And if we can do that, then it’s

that

relationship that helps people escape these kinds of unwanted desires.”

“But what if somebody wants to be that way or something?” Andrea Hurlitz asked, and then she told a story about some documentary she had seen at the church she used to go to back in Tennessee about how the only true cure for homosexuality was AIDS, which she said was God’s way of curing it.

Reverend Rick listened to her story, and he nodded in places where you could tell Andrea thought she was making some big point; but when she was finished he said, breathing in some and tucking that hair again, “I’ve seen that film before too, Andrea, and I know people who hold that belief, but my own relationship with Christ has taught me compassion toward my neighbors no matter what the sins they’re struggling with.” Pause, hair tucking. “I know a bit about how this works from the inside. I was a teenager who struggled with homosexual desire, and I feel grateful, really, I feel blessed, that I had friends and spiritual leaders to help me, and I still have people help me. Mark, chapter nine, verse twenty-three: ‘Everything is possible for him who believes.’”

Nobody knew where to look after that. I’d lock eyes with someone across the circle and we’d shift our stares, fast, to someplace else. I hadn’t known that piece of the puzzle, that background about Rick, and judging from the faces of most of my fellow Firepower members, neither had they. Except for Clay Harbough, who looked like he was unsuccessfully attempting to eat a grin, his mission of revelation apparently accomplished.

“Do you all have more questions about this?” Rick asked. “This is not a shameful secret for me anymore. You can bet that it once was, but in Christ I have found redemption and a new purpose. So let’s go ahead and talk about anything you want to talk about.”

I had many, many questions, and I didn’t dare look at Coley, but I knew that she did, too. There was no way that I was raising my hand, though, and nobody else did either until Lydia asked, “So do you have a girlfriend now?”

Everybody laughed, Rick included, and after he told us

not at the moment,

but not for lack of trying

, and we all laughed more, somebody asked something about the different kinds of sexual brokenness and that led to a discussion of promiscuity in teenagers in general and then to the

appalling

teenage pregnancy rates around the country and then, predictably, to abortion, and we seemed to have fully moved on.

After the meeting Coley clumped with a couple of other members around the snacks table. Rick had put a pile of pamphlets about his God’s Promise Christian Discipleship Program at one end next to a plate of peanut-butter brownies. She picked up one of the pamphlets and pretended to nonchalantly peruse it and then slipped it into her purse. I wanted to take one too, though I can’t exactly say why. I guess just to see what it said, to see if there were like pictures of the kids who went there, more information about what actually went on, but there was no way that I could just grab it in front of everybody. Not like Coley could. She didn’t need to sneak it, because nobody would ever suspect that she might be taking it because she needed to go there, or at least thought that maybe she did. Not

the

Coley Taylor of

Brett & Coley

. No way.

Big Thing No. 4—the Really Big Thing: Just a few days after Reverend Rick’s visit, Coley got an apartment in Miles City. Her own apartment. Maybe that sounds big-city or glamorous or something, but it wasn’t at all unheard of for kids whose families lived on ranches miles and miles away from Custer High. There were easily a couple dozen such students—four of them sharing a little bungalow not far from the school, or somebody renting out an old lady’s top floor or, like Coley, a one-bedroom sixth-floor walk-up in the Thompson apartment building downtown, just a few blocks off Main Street.

Coley had mentioned the possibility to me before, but when Ty hit a deer driving back to the ranch one night, and then a couple of days later drove off the road and into an irrigation ditch (that having more to do with the alcohol he had been drinking than the rutted and curvy ranch roads), Mrs. Taylor decided that an apartment in town would be good for them all. Coley would stay there Sunday through Thursday nights during the school year; Ty could use it when he’d had too much to drink; and Mrs. Taylor would go there to sleep a few hours after she worked a twelve-hour shift and was too bleary to make the trip out to the ranch. But ultimately, it was to be Coley’s place.

She told me that it was happening for sure when she came to pick me up at Scanlan. I was still on left chair, the lake wrapped in shadows from the cottonwoods and a family of out-of-towners playing a loud game of Marco Polo just beyond the rope line.

We’d been surprisingly steady since the Firepower meeting, since Coley had taken that pamphlet. In our typical style, we hadn’t even talked about it, and we’d since been to the movies without any noticeable change in our routine. But Brett would be back in a week, and school would start fifteen days after that, and even if we weren’t talking about it, our routine was most definitely gonna have to change.

Still, that evening, Coley in dirty work clothes, grit and dust in her hair, stood next to my guard stand and leaned one arm against its warm wood and flaky paint and told me in this excited voice of hers how great this apartment was going to be, despite the fact that she said it currently smelled like

bleach and feet

, and how she wanted me to help her decorate it, and how her mom had already taken her to Kmart and bought her a red metal teapot and a soft yellow bathmat and a bunch of vanilla and cinnamon candles, and how the bathroom had a claw-foot tub and black and white tiles, and how we could start moving her in the very next day.

L

indsey once tried to explain to me this

primordial connection

, she said, that all lesbians have with vampire narratives; something to do with the gothic novella

Carmilla

and the

sexual and psychological impotence of men when facing the dark power of lesbian seduction

. As such, I’d heard all about “the scene” in

The Hunger

before ever seeing it for myself. I did eventually rent it, though, and while “the scene”—wherein Catherine Deneuve as Miriam, the ageless Egyptian vampire, and Susan Sarandon as Sarah, the doctor on aging, tumble around Miriam’s big silk-sheeted bed and totally get it on, and also do their vampire-blood-sisters-exchange thing with white curtains billowing all around them, blocking the shots of their tangled bodies at the most inopportune of moments, forcing me to rewind again and again—

is

very steamy and erotic and all of the things Lindsey described it as, it’s what comes before that scene that gets my vote as the much, much hotter moment.

That’s the moment when Susan/Sarah, flushed by Catherine/Miriam’s piano playing—and probably also by her low voice and hypnotic but sometimes hard to decipher accent—spills three drops of bloody sherry on her very white, semitight T-shirt, and then there’s a jump-cut to her attempting to rub it out with a wet rag, creating a fraternity-movie-type wet T-shirt situation, and at that point all Catherine Deneuve has to do is walk behind her and gently trail her fingertips along Susan’s shoulders and cause this intense moment of eye contact between the two of them, and it’s go time: Susan Sarandon just peels off the T-shirt entirely maybe five seconds after that.

And even though it was just some artsy vampire movie with David Bowie and two, to my knowledge, non-lesbian-in-real-life actresses, that single moment, the shoulder touch, the way they met eyes, it seemed completely true to me, and way more powerful or erotic or whatever than the sex itself. Maybe that’s because the first time I watched

The Hunger

I’d actually

had

a moment like that, but none of the “sex itself.”

I had rented it sometime in my first months after knowing Lindsey, but at that point she’d given me so much lesbian-knowledge-building pop-cultural homework that I guess it was one assignment I’d forgotten to mention to her as checked off the list, because she sent it to me, a videotape in the original box with a pink

PREVIOUSLY VIEWED MOVIE

sticker placed inconsiderately over Catherine/Miriam’s face, in a care package that came all the way from Anchorage, Alaska. A care package that I didn’t really deserve given that I’d only written her once since the start of summer, and even more so considering how I’d blown off her plans for our Alaskan reunion in order to court Coley Taylor.

The package was waiting on the dining-room table for me when I got home from work in a hurry to shower and change. For the first time in a long time Coley wasn’t with me. This was how we’d planned it. She was at her new apartment, the one that had been swarming with family and friends the last couple days, Ty and his cowboy cronies hauling furniture and hanging shelves; Mrs. Taylor’s crowd, nurses and GOP-goers, bringing old dishes and pots and pans; people stopping by with cases of soda, with frozen meals, with potted plants. Now finally everything was settled, ready to go, and we had made a date for our first ever nontheater, private-screening-for-two movie night. I was supposed to swing by Video ’n’ Go and rent something, anything, to serve as the outward reason for our get-together—one to be spent completely alone, with a door that locked, both deadbolt and chain, and a brand-new queen-size bed in the other room.

But then smack in the middle of these plans came this package from Lindsey. I opened it while taking the stairs to my room, two at a time, trying to both tear apart the box and also to pull off articles of clothing as I went, unwilling to let any amount of time that I could be spending with Coley go to waste. I got a paper cut from the corner of the cardboard, one that I aggravated by pulling at the packing tape. I littered shredded newspaper as I went. I didn’t stop to pick it up. Inside, along with

The Hunger

, were two mix tapes, a bag of chocolate-covered nuts and raisins labeled Real Alaskan Moose Droppings, a snow globe with a fly-fishing grizzly bear inside, and a postcard with a couple of busty and tanned big-smiling women in neon bikinis standing in a very large, seemingly very cold snowbank, pines and cedars all around them, and the neon purple caption:

Alaska’s Finest Wildlife

.

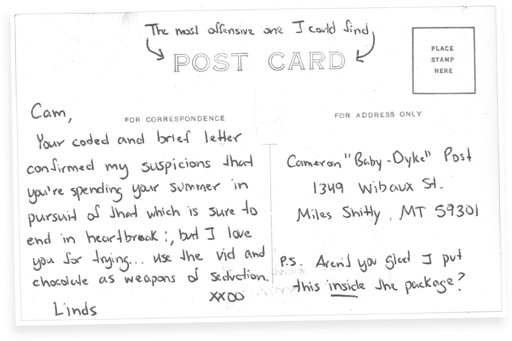

On the back of the postcard Lindsey had written: