The Miseducation of Cameron Post (34 page)

Read The Miseducation of Cameron Post Online

Authors: Emily M. Danforth

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Homosexuality, #Dating & Sex, #Religious, #Christian, #General

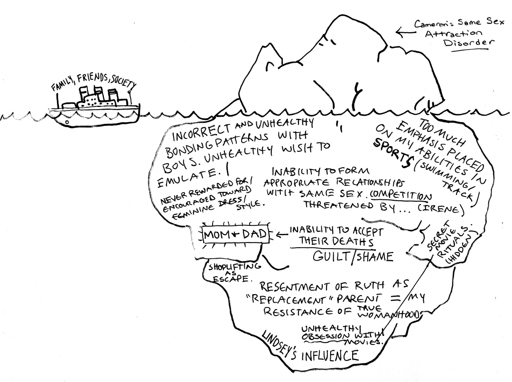

“Then yes,” I said, looking at her and speaking deliberately. “The iceberg’s tip, as it is drawn in this picture, features many sharp angles and pointy protrusions, and it is looming ahead of the ship in a precarious manner.”

“Yes,” she said. “It is. That wasn’t so hard. And because it’s so big and so scary, it’s all the people on the ship want to focus on. But we know it’s not the real problem, is it?”

“Are we still talking about the drawing?” I asked.

“It doesn’t matter,” she said. “The real problem for the people on the ship . . .” She paused to tap-tap her finger on the drawing, right on top of the words

Family, Friends, Society

; then she took that same finger and pointed it at me, getting me to look at her face, before continuing. “The

real problem

is the massive, hidden block of ice holding up that scary tip. They might manage to steer their ship around the ice above the surface but then crash directly into even bigger problems with what’s beneath. The same is true for your loved ones when it comes to you: The sin of homosexual desire and behavior is so scary and imposing that they become fixed on it, consumed and horrified by it, when in actuality, the big problems, the problems we need to deal with, they’re hidden away below the surface.”

“So are you gonna try to melt away my tip?”

Reverend Rick laughed. Lydia did not. “Something like that, actually,” Rick said. “But

we’re

not doing anything; you’re going to do it. You need to focus on all the things in your past that have caused you to struggle with unnatural same-sex attractions. The attractions themselves shouldn’t be so much the focus, at least not right now. What’s important is all the stuff that came before you were even aware of those feelings.”

I thought about how young I was when I first considered kissing Irene. Nine. Maybe eight? And there was my crush—you could call it a crush, I think—on our kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Fielding. What could have possibly happened to me to make me “struggle with same-sex attraction” by the age of six?

“What are you thinking?” Rick asked.

“I don’t know,” I said.

Lydia sighed big. “Use your words,” she said. “Your big-person words.”

I decided I hated her. I tried again. “I mean, it’s interesting to think of it this way. I haven’t ever really, before.”

“To think of what?” Lydia asked.

“Homosexuality,” I said.

“There’s no such thing as homosexuality,” she said. “Homosexuality is a myth perpetuated by the so-called gay rights movement.” She spaced out each word of her next sentence. “There is no gay identity; it does not exist. Instead, there is only the same struggle with sinful desires and behaviors that we, as God’s children, each must contend with.”

I was looking at her, and she at me, but I didn’t have anything to say, so I dropped my eyes to my iceberg.

She kept going, getting increasingly louder. “Do we say that someone who commits the sin of murder is part of some group of people who have that identity feature in common? Do we let murderers throw themselves parades and meet up in murderers’ clubs to get high and dance the night away and then go out and commit murder together? Call it just another aspect of their identity?”

Reverend Rick cleared his throat. I kept looking at my iceberg.

“Sin is sin.” She seemed pleased with that, so she said it again. “Sin is sin. It just so happens that your struggle is with the sin of same-sex attraction.”

I could hear Lindsey in my head telling me to say

Really? Well, if homosexuality is just like the sin of murder, then who dies, exactly, when homosexuals get together to sin?

But Lindsey wasn’t sitting there with the two of them. And Lindsey wasn’t exiled to Promise for at least a year. So I kept the Lindsey part of me quiet.

“How are you feeling about all this?” Rick asked. “We’re throwing a lot at you, I know.”

“I’m good,” I said, too quickly, without thinking about his question at all. I added, “Well, maybe I’m fine.” I had a headache. The room we were in, this little meeting space off Rick’s office, was just big enough for the table and three chairs we now occupied, and the small space smelled too thickly, too sweetly, of the potted gardenia sitting on a shelf beneath the window, all shiny leaves and maybe half a dozen blooms, some of them already brown and decaying on the stem. Being there made me almost wish for Nancy the counselor’s office: the couch, the celebriteen posters, the bites of food from the office staff, the lack of sin indicated by my presence.

“So what do I do with this?” I asked, holding up my iceberg.

Rick pressed both his palms to the table in front of him. “We’re going to spend your one-on-ones, as many as it takes, attempting to fill in the stuff below the surface.”

I nodded, even though I wasn’t sure what he meant by that.

“It will be hard work,” Lydia said. “You’ll have to confront things I’m sure that you’d rather not face. One of the most important first steps is for you to stop thinking of yourself as a homosexual. There’s no such thing. Don’t make your sin special.”

Lindsey in my head said,

Funny—my sin seems pretty fucking special considering that you’ve built an entire treatment facility to deal with it

. What I said out loud, though, was “I don’t think of myself as a homosexual. I don’t think of myself as anything other than me.”

“That’s a start,” Lydia said. “It’s uncovering just who the ‘me’ is, and why she has these tendencies, that will be the challenge.”

“You’ll do just fine,” Rick added, smiling at me his genuine Rick smile. “We’ll be here to support you and guide you through all of it.” I must have still looked doubtful, because he tacked on “Just remember that I’ve been right where you are too.”

I was still holding my iceberg. I shook the paper back and forth a few times, fast, and it made that cool, sail-flapping noise paper makes when you shake it like that. “So I should take this with me?”

“We’d like you to hang it in your room,” he said. “You’ll write on it after each one-on-one.”

That iceberg was my first, and only, decoration privilege for the following three months. I hung it directly in the center of the bare wall on my side of the room. I started looking for everyone else’s icebergs, now that I knew what to look for. Sometimes disciples (we were supposed to call ourselves disciples and to think of ourselves as disciples of the Lord and not just fucked-up students) who were further along in their programs would have partially buried their icebergs beneath the typical kinds of ephemera that show up on teenagers’ walls—though the posters and flyers and pictures belonging to Promise teens had more to do with Christian activities and bands and less to do with, say, naked cowboys or Baywatch girls. But adolescent collages are all sort of the same, regardless, and the iceberg photocopies were distinctive enough that I could eventually spot them.

Written in the ice below the surface on each disciple’s picture were phrases and terms that didn’t make much sense to me until my own one-on-ones progressed and I started writing similar kinds of things.

I studied everyone else’s

below-the-surface

troubles with such regularity that I can remember some of them pretty much word for word:

Viking Erin (my roommate):

Too much masculine bonding with dad over Minnesota Vikings football. Jennifer’s extreme beauty = feelings of feminine inadequacy (inability to measure up), resulting in increased devotion to Girl Scouts, attempting to prove my worth (as a woman) in inappropriate ways. Unresolved (sexual) trauma from seventh-grade dance when Oren Burstock grabbed my breast by the water fountain.

Jennifer was Erin’s sister, and there were some pictures of her on the bulletin board. I didn’t blame Erin for feeling in-adequate: Jennifer was a stunner. I asked Erin about why they let her decorate with Minnesota Vikings colors and memorabilia if it was such a problem area for her.

She had her answer all worked out. She’d obviously spent some time on it, because she said it just like I’m sure Lydia had said it to her oh so many times. “I have to learn to appreciate football in a healthy way. There’s nothing wrong with being a woman who is a fan of football. I just don’t want to look to my football bond with my father to confirm my sense of self, because the confirmation confuses my gender identity, since the activity we’re bonding over is so masculine.”

Jane Fonda:

Extreme, unhealthy living situation at commune—Godlessness, pagan belief systems. Lack of (stable and singular) masculine role model in upbringing until adolescence. Inappropriate gender modeling and “accepted” sinful relationship: Pat and Candace. Early exposure to illegal drugs and alcohol.

Adam Red Eagle:

Dad’s extreme modesty and lack of physical affection caused me to look for physical affection from other men in sinful ways. Too close with mom—wrong gender modeling. Yanktonais’ beliefs (winkte) conflict with Bible. Broken home.

Adam was the most physically beautiful guy I’d ever met. He had skin the color of coppered jute and eyelashes that looked like a glossy magazine ad for mascara, though you couldn’t often see them because of his black, shiny hair, which he let hang over his face until Lydia March would inevitably come at him with a rubber band stretched out between her thumb and pointer finger, saying, “Let’s get it pulled back, Adam. There’s no hiding from God.”

Adam was tall and he had long muscles and he held himself like a principal dancer with the Joffrey, all grace, all refined power and strength. Sometimes we ran the trails together on the weekends, before the snow came, and I found myself checking him out in ways that surprised me. His father, who had only recently converted to Christianity “for political reasons,” Adam said, was the one who’d sent him to Promise. His mother opposed the whole thing, but they were divorced, and she lived in North Dakota, and his dad had custody and that was that. His father was from the Canoe Peddler band of the Assiniboine, a voting member in the consolidated Fort Peck Tribal Council, and also a much-respected Wolf Point real estate developer with mayoral ambitions, ambitions that he felt were threatened by having

a

fairy for a son

.

Helen Showalter:

Emphasis on me as athlete: maleness reinforced with softball obsession (bad). Uncle Tommy. Body image (bad). Absent father.

Mark Turner:

Too close with mother—inappropriate bonding (with her) over my role in church choir. Infatuation with the senior (male) counselors at Son Light’s Summer Camp. Lack of

appropriate

physical contact (hugging, touch) from father. Weakness of character.

It wasn’t difficult to tell Reverend Rick the things I knew he was looking for me to say. He would shut the door to his office and ask about my week and my courses, and then we would start up wherever we had left off and I would tell him some story about me competing with Irene, or about how I hung out more with Jamie and the guys than with girls my age, or something about Lindsey’s influence over me. We talked about Lindsey a lot—her big-city powers of suggestion, the enticement of that which is exotic.

It wasn’t that I was lying to Rick, because I wasn’t. It was just that he so believed in what he was doing, what we were doing, whatever it was. And I didn’t. Ruth was right: I hadn’t come to Promise with a “teachable heart,” and I had no idea how to go about making the heart I did have into the other version.

I liked Rick. He was kind and calm, and I could tell that when I told him yet another story about my being rewarded and encouraged for masculine behaviors or endeavors, he thought we were really getting somewhere, that this “work” was benefiting me, and that I would eventually come to embrace

my worth as a feminine woman

and, in doing so, open myself up for

Godly, heterosexual relationships

.

Lydia, on the other hand, was sort of scary, and I was glad that, at least for now, I had one-on-ones with Rick. I’d heard people describe someone as “prim and proper” before, but Lydia was the first person I think I would have used those two words to pin down. When she led Bible study, or even if I saw her in the dining hall (which was not that big a room at all, certainly not a hall), or wherever, she instantly made me feel like I was sinning right then, pretty much just by being alive, by breathing, like my presence was the embodiment of sin and it was her job to rid me of it.

By Thanksgiving my own iceberg looked like this:

There were nineteen of us disciples that fall, which was an impressive six more than the year before. (Ten of the disciples were returners.) Twelve guys, seven girls, plus Reverend Rick, Lydia March, four or five rotating dorm monitors and workshop leaders, and Bethany Kimbles-Erickson—a twenty-something, semirecently widowed teacher who drove her grunting maroon Chevy pickup from West Yellowstone Monday through Friday to oversee our studies. (She and Rick were also now dating. Very chastely.) Out of the nineteen of us there were, at any given time, at least ten disciples really committed to the program, to conquering the sins of homosexual desire and behavior, to melting their iceberg tips in the hopes of eternal salvation. The rest of the disciples got along pretty much the way that I did: faking progress in one-on-ones, amicable interactions with staff, and burning off steam through a series of sinful, thereby forbidden, thereby secret interactions with each other.