The Misremembered Man

Read The Misremembered Man Online

Authors: Christina McKenna

Tags: #Derry (Northern Ireland) - Rural Conditions, #Women Teachers, #Derry (Northern Ireland), #Farmers, #Loneliness, #Fiction, #Romance, #Literary, #General, #Love Stories

My Mother Wore a Yellow Dress (memoir)

The Dark Sacrament (non-fiction)

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2008 Christina McKenna

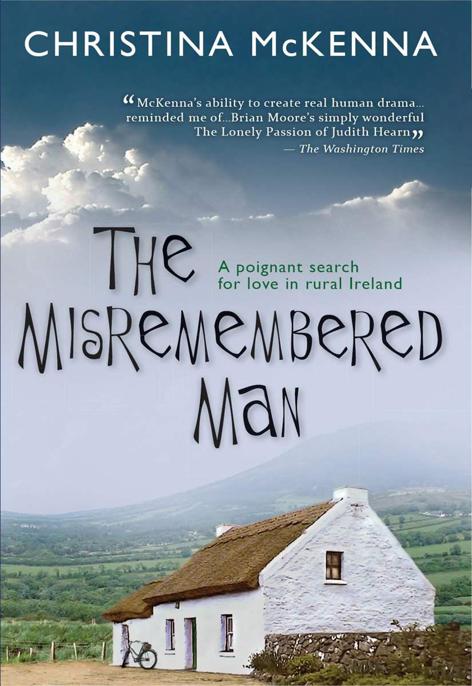

Cover photograph of thatched cottage in Killanin ©

Maire Mc Donagh Robinson.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by AmazonEncore

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN: 978-1-61218-073-1

To Mr. Kiely as ever

Everyone has conscience enough to hate; few have religion enough to love.

Henry Ward Beecher,

Proverbs from Plymouth Pulpit,

1887

J

amie McCloone rose from his bed, hotly dazed and stiff with undiagnosed lumbago.

Jamie was not an elegant sight first thing of a morning, most especially after a night of drink and embittered sleeplessness; a night in which he’d tossed and wept and brought the name of Jesus down and cursed his mother, in fact all women in general—nuns in particular—and wished a plague on all children under ten-and-a-half months (this being the age at which his mother had abandoned him, in a Curley’s Discount shopping bag, on the stone steps of the St. Agnes Little Sisters of Charity convent, in the city of Derry, one cold November morning in 1934).

From that day on he’d always feared waking up in the claustrophobic darkness of some colossal pouch; feared being slapped on his bare bottom by a female hand; feared jangling keys and rosary beads, being locked inside boxes and lavatories, being fed thin gruel from a wooden bowl and cod-liver oil from a spoon. Such were the effects of those seminal events that, over the years, had carved deep pathways into the lumpy geography of his brain, rendering him incapable of forgetting the injury that had been done to him, making him wary of people and anxious of change, and forcing him to live a lesser life, full of empty dreams and broken hope, without much joy, without much meaning, without much love.

Jamie yawned extravagantly, ran a hand over his stubbly cheeks and tweaked his right ear. It stood up slightly higher than the other, giving him the look of being yanked forever heavenward by a celestial hand. This minor deformity had encouraged bullying in the schoolroom and funny stares on the street. When other boys fantasized about train sets and blazing cowboy guns, Jamie had dreamed of owning a perfect set of ears.

Sitting now on the edge of the bed, he stared down at his rough, forty-one-year-old feet, wondering idly about their uses; saw them, in that moment, as instruments of brute abuse, for stomping out the vision of the bitch that his mother must surely have been. Jamie was not a violent man, but on this particular morning—perhaps because his hangover seemed more severe than usual—he sat for longer, simply looking down, taking pleasure in the fanciful vengeance that was his, while outside the birds chirped, the rooster crowed, the dog barked, the cows roared (to be fed) and the day broke, sending a blush of hazy sunshine through the window.

The clock in the hall struck seven, jerking him free of the reverie. He rose carefully and proceeded to dress himself.

First, the red plaid shirt. Next, his army surplus trousers, zipped and buttoned over his expanding stomach, and needlessly secured by a set of brown suspenders, which he hoisted and snapped into place with a satisfied grunt. Then his Wellington boots, caked and frilled in last winter’s mud, from their station behind the bedroom door.

In the back scullery he filled the pock-marked kettle, put a match to the gas ring, retrieved a chipped mug from under a pile of dishes in the greasy sink and proceeded to make tea.

He moved about the cramped quarters with exaggerated caution, as if balancing a hundredweight sack of coal on his head. As if delicate antennae protruded from every part of his body, sensitive to the touch, as if he were made of breakable stuff that needed careful tending and he were a man treading a tightrope made of twisted, shattered glass. Jamie McCloone’s limestone cottage in the townland of Duntybutt was a two-up, two-down structure, which he’d inherited from his adoptive aunt and uncle, Alice and Mick. It had changed little in its one-hundred-and-five-year history. No woman had lasted long enough under its broken roof to clean and polish its roughness; no man of a sensitive nature had ever entered it without catching his breath. Father Brannigan, the parish priest, on his monthly mission to collect his stipend, would often falter on the threshold, flourish a handkerchief and make a show of blowing his nose noisily so as not to cause offense. “It’s the bronchitis, Jamie. Never leaves me, so it doesn’t. The little cross I have to bear.”

Jamie poured the tea with a quivering hand and carried the mug and his aching carcass to his armchair by the banked hearth fire. He reached for a Valium and swallowed it. The medication was his defense against too much reality, too much reflection on the past. Since his uncle’s death, he’d been forced again and again to wade through the quicksand of his childhood. The pills helped him keep his head above the mire.

The demanding voices of the farmyard came to him in a muffled discordance; each one demanding feeding, each one reminding him of the work that lay ahead.

“I’ll be out in one wee minute!” he shouted. “You’ll be fed soon enough, all right.”

He leaned over to poke the slack-filled fire into life. It responded with a slow hissing—the divil rousing hisself, thought Jamie. Without warning it spat out a chip of coal, which flew across the floor, ricocheted off a table leg and bounced under Jamie’s armchair, where it joined a slew of others, adding to the accumulated detritus that was his home. He replaced the poker on the hearth, sat back in the chair and stared down at his lap.

There was a tear in the left knee of his trousers. Two weeks earlier he’d snagged it on a spur of barbed wire while tethering the goat to a post in a hillside field. Every morning since this small accident Jamie would sit, study the rent fabric, put his forefinger into the hole, wiggle it about a bit and think that maybe he’d need to put a stitch or two in it before it got any bigger. His eyes would then drift guiltily to the glass case where, propped against a green-rimmed plate, stood a fan of sewing needles in a gaudy packet cut to the shape of a flower-filled basket. He remembered buying them from a tinker woman, who’d gripped his arm after pocketing his penny and said: “God’ll reward yeh, son. Dere’s darkness round you but dere’s brightness if you look for it.” Her gypsy eyes glittered in the noonday sun and a gold tooth winked in a cavernous mouth.

Jamie pondered the image of the old woman for a minute and concluded that since it was a good while ago maybe the needles would be rusted by now. Even if they weren’t rusted, where would a body get a bit of thread? And at the end of the day, sure, wouldn’t it only be the two cows and the pig that would be seeing him anyway?

Thus mollified, he sighed and smiled to himself, the matter of the torn trousers and the needles and the tinker woman bundled back into that “It’ll-wait-another-wee-while” box that sat tightly fastened at the back of his mind. A box that grew weightier with neglected jobs and weak intentions carried along by the wifeless Jamie, a man possessed of a thousand petty deferments.

He would have deferred the farm work too, but since Uncle Mick was no longer around to tighten the fences, scutch the corn, fill the troughs with J.J. Bibby Farmfeed, and switch an ashplant off of a cow rump when required, the work fell to him. He saw the onerous toil of the day stretch out before him. And, as was his wont, he believed in the efficacy of having a good wee rest before he got going. However, the longer he sat, the more urgent the notes from the farmyard animals grew.

After ten minutes he rose abruptly, drained the last of his tea, gave the mug a hasty lick under the tap, returned it to the sink and shuffled back to the bedroom to groom himself.

Jamie’s ablutions consisted of fixing his hair—his oh-so-unsuccessful hair—and giving his face a rub (quite literally with his hand as opposed to a damp cloth). He lowered his eyes to the pockmarked piece of mirror that sat on the tallboy and looked at himself in dismay. His comb-over fell down on his left shoulder like a she-ass’s tail. A deep scar ran from under his right eye to the jawline, as if all the pain of his life had been cried and cut there. His long nose and morose mouth stopped him from being handsome, but his blameless green eyes made one forgive the imperfections of his face.

He sighed at the image that stared back at him; an ancient prophet with a scalp condition. Every morning he experienced a pang of regret for his lost locks, followed by a sharp admonishing voice—

“Jezsis, look at the state of ye!”

—before fixing his hair.

Thus deflated and thoroughly depressed, he hurriedly arranged the precious strands over his balding crown, held them carefully at one side, and shoved on his cap to anchor all in place. With that distasteful act accomplished, this son of the soil was ready to face the day.

Personal hygiene did not feature in his weekday routine, which took Jamie from bedroom to barn in five minutes flat. On Sunday mornings, though, he made a special effort with a razor, comb and a basin of soapy water, before facing his Maker at Mass.

He was not to realize, however, on this fine summer morning, that he, Jamie McCloone, would soon be making such an effort with his appearance that even his Maker would have to be content with second place.