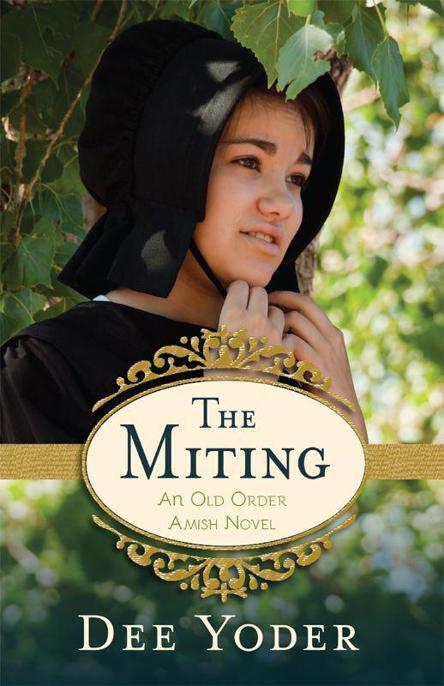

The Miting

The Miting: An Old Order Amish Novel

© 2014 by Dee Yoder

Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel, Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505.

The persons and events portrayed in this work are the creations of the author, and any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

Scripture quotations are taken from either the King James Version or the Holy Bible, New International Version

®

, NIV

®

. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.

TM

Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide.

www.zondervan.com

.

Use of this ebook is limited to the personal, non-commercial use of the purchaser only. This ebook may be printed in part or whole for the personal use of the purchaser or transferred to other reading devices or computers for the sole use of the purchaser. The purchaser may display parts of this ebook for non-commercial, educational purposes.

Except as permitted above, no part of this ebook may be reproduced, displayed, copied, translated, adapted, downloaded, broadcast, or republished in any form including, but not limited to, distribution or storage in a system for retrieval. No transmission, publication, or commercial exploitation of this ebook in part or in whole is permitted without the prior written permission of Kregel Publications. All such requests should be addressed to:

[email protected]

This ebook cannot be converted to other electronic formats, except for personal use, and in all cases copyright or other proprietary notices may not modified or obscured. This ebook is protected by the copyright laws of the United States and by international treaties.

For Rachel, Maryann, and Matty.

Your journeys are my inspiration.

C

HAPTER

O

NE

L

eah Raber sank wearily onto the porch swing, causing the chains to jangle. She leaned her head back, closed her eyes, and imagined herself free—her skirt and apron flung carelessly over the branches of a prickly mulberry, her legs running to the pond, her hair blowing behind her as she leapt into cool, deep waters. She could almost feel the splash as she plunged into the secret world of water and swam among the fronds of the dark pond bottom, the silky liquid sliding against her arms and legs as her feet kicked out, over and over.

A cow mooed, and Leah came up for breath, opening her eyes to the reality of the hot, unrelenting sun.

Leah’s gaze traveled around the yard to the barn, where she spotted Benny chasing a few of

Maem

’s setting hens away from the road. His laughter carried across the field, his cheeks rosy and his bowl-shaped haircut flopping up and down while he chased the squawking birds. Life used to seem so simple.

From outward appearances, Leah could certainly see why

Englishers

would think her family’s life was idyllic. But they didn’t have to wear the long skirts and

kapps

and heavy shoes in the summer. They didn’t have to follow endless rules … forever.

Pressing her feet against the gray boards of the porch, she stopped swinging and thought about going inside to help

Maem

put lunch on the table. With a sigh, she wiped the sweat from her face and stood up.

“Might as well get to it.”

The kitchen felt even hotter than outside.

Maem

had started the weekly bread baking before five that morning in an effort to finish the task before the heat of the day, but the wood-burning stove had held its warmth. A fan or a quick-cooling propane stove, anything to relieve the heat, would be so nice in the kitchen.

“Another silly thing the

Ordnung

won’t allow …”

Maem

turned with a puzzled frown. Wisps of damp hair clung to her flushed cheeks, and perspiration beaded over her lips. “Did you say something, Leah?”

“Just … oh, nothing.”

Maem

bustled by to get some of her homemade, sweetened peanut butter spread and sweet pickles from the pantry. Her brow furrowed again, but a smile played at her lips. “I never know what you’re going to surprise me with.”

Leah reached into the bread box for the only loaf of wheat bread left from last Saturday’s baking. Slicing and arranging the bread on a white pottery plate, she hummed a song she’d heard the last time she’d been with her friend Martha.

Martha—against her parents’ and the church’s wishes—was dabbling in the English world. While some Amish sects turned a blind eye to a teen’s running-around years, their bishop preferred that children not flirt with sinful English ways. Just last week, Martha and her boyfriend, Abe Troyer, had stopped by Leah as she walked along the road. They were in Abe’s beat-up truck on their way to Ashfield to shop. Country music had blared from the radio, and the joyous freedom emanating from her friends made Leah long for something that seemed just out of her reach. A few of the words she’d heard still stuck in her head.

“Oh, I wanna go to heaven someday—I wanna walk on streets of pure gold—I wanna go to heaven someday, but I sure don’t wanna go now.”

“Leah!”

Maem

’s sharp tone brought her back to the present, and Leah’s cheeks flushed as she realized she’d sung aloud. Not something her parents would want her to sing, that’s for sure.

“Sorry.”

Maem

lowered her gaze and shook her head slightly, her face drawn. Lately, Leah couldn’t keep count of the number of times a day she made her mother frown. It didn’t take much. The set of her jaw showed her disappointment.

Leah slammed the cheese knife down on the counter in frustration.

Can’t even sing in my own home—can’t sing anything but Sunday singing songs. Boring.

She whirled around to escape back onto the porch, but

Maem

caught her arm and motioned her to the table.

“There’s something

Daet

and I want to talk with you about. We’re concerned for you. I know it’s your teen years and at least one of your friends has fiddled with English ways—”

“

Maem—

”

“No. Listen to me, please, for just a minute. So far, you haven’t acted like you wanted to join Martha, but we’re worried she’s influencing you.”

Leah ducked her chin, avoiding her mother’s gaze. She’d known this talk was coming.

Best to get it over with.

“

Maem

, don’t you remember your teen years? Don’t you remember longing for freedom? Just a little bit of time with no one telling you exactly what to do, what to wear?” Leah lifted her gaze to her mother, willing her to show a glimmer of compassion.

Maem

’s stony face looked back, fueling Leah’s determination.

“Didn’t you ever wish that you could blend in—that people wouldn’t stare at you, point at you, laugh at you? Why do we have to live this way? I want to understand,

Maem

, I really do, but I just don’t see what we gain by living this way. So … so … backward. I could even accept being hot all summer long if I just understood why. So many things are wrong and sinful—too many to keep track of. But some of those same things are okay in other Amish communities. Like being allowed to have a phone shed in the driveway. Why can other Amish have that but not us?

Why?

”

Realizing she had raised her voice, she clamped her jaw shut. She hadn’t meant to be disrespectful.

Maem

held her gaze, but her cheeks had gone white in spite of the heat of the kitchen. When she finally spoke, her voice was full of reproach and sorrow.

“You surprise me, Leah. You really do. You’ve never talked like this before. Your

daet

won’t be happy to hear you saying these kinds of things. And no, I did

not

question the things you seem to be so unhappy with.”

Maem

swiped a dish towel across the table in frustration. “What’s to question? You have a good home, good family, and a hard-working

daet

and

maem

. Your brothers and sister are good to you, too. The church—”

“

Maem

, I just want you to understand me. Even if you’ve never thought like this, can’t you think about what I’m saying? Just let me have a little breathing room, okay?”

“Breathing room for what?”

Maem

exclaimed. “Putting the light in your window as some girls do to attract

buves

driving by? Sneaking away in some boy’s sinful car and riding around drinking, smoking all night? Listening to godless music and wasting your life trying to find out what the English world has to offer you? Let me tell you this: the English have nothing to offer you. Believe me. Nothing.”

“How do you know that,

Maem

? How do you know! You’ve spent your whole life in this place and done everything the bishop and the church told you to do.” Leah jumped up from the table and threw her hands out imploringly. “I’m not like you and

Daet.

I need some freedom, and I want to do things other than staying here in this house, on this farm. I don’t want to spend all my time—”

The back screen door banged.

Daet

stood in the kitchen. Sawdust and small curls of wood covered his face and his blue cotton work shirt. He undoubtedly had heard her last words, but he silently went to the sink and washed his hands, then came to the table and sat down next to

Maem

. Fear of his reaction kept Leah from storming out.

The screen door banged again as her brothers and sister rushed in for lunch.

Maem

and

Daet

exchanged a look, then bowed their heads for silent prayer. When he finished praying,

Daet

pointed to Leah’s vacated chair. She cautiously eased into her seat and took a slice of bread.

“I think someone should catch that mean

hohna

, as soon as lunch is over.” Benny’s blue eyes sparkled. “I can do it. I’m old enough now.”

Maem

wiped a glob of mustard off his cheek. “Being a second grader does make you old enough to do many things to help out, but I think you’d best leave that old rooster alone. He’ll claw you if you try to catch him.”

“But don’t you think he’d make pretty good

bott boi

?”

Ada snickered. “He’s ancient. And he’s mean, so I vote for

bott boi

, too.”

“Pretty much up to

Maem

when a chicken’s life is over around here.”

Daet

nudged Leah’s older brother, Daniel. “But she gets attached to ’em, too. Isn’t that why we don’t have chicken

bott boi

for

suppah

much,

Maem

?”

“That rooster has much more life left in him. We won’t be using him for pot pies any time soon. Now hurry and eat your lunch.

Daet

wants to

schwetz

with your sister.”

The siblings’ eyes swiveled to Leah. Deliberately ignoring their stares, she scrutinized her uneaten bread, her lips pressed tightly together.

The family finished the meal in silence, her brothers and sister seemingly aware of the awkward strain between their parents and Leah. Benny finished his milk with a long, loud gulp, wiped his mouth on his sleeve, then scurried out of the kitchen behind Ada and Daniel.

Finally

Daet

pushed his plate back and leaned forward, resting his fists beneath his chin. He sighed, and his beard bobbed as he swallowed.

“Leah, I’m sorry to say I have no respect left for your friend Martha—”

“

Daet!

That’s not fair—”

He held up his hand. “No. I’ve thought and prayed about this for a while, and your

maem

and I have talked this over. You’re being influenced by her and what she’s doing.”

His gaze held Leah’s firmly, and though he said nothing else about her friendship with Martha, his message was clear: Martha would not be a welcome visitor to their home as long as she was

rumspringen

with the English. She was definitely outside the will of the church and going against the

Ordnung

letter in open rebellion.

“I also want you to consider joining the church sooner—as Daniel did. He didn’t have to join when he was only seventeen, but he decided it was best. I think once you’ve made that decision, all these worries and problems you’re having will stop pestering you.”

He stood up, signaling an end to the conversation, and went to the back door. As he pushed open the squeaky screen, he looked back at Leah, a tilted grin clearing his face of lingering anger. “By the way, Jacob Yoder is coming today to help me unload and stack lumber. He should be here in about an hour.”

An unexpected wave of remorse rolled over Leah, and she moved quickly to her father, giving him an impulsive hug. He clumsily patted her arm before he hurried back to work in his furniture shop.