The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) (6 page)

Read The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) Online

Authors: Jo Owen

Most organizations have a natural tendency to underprice: this shows a lack of confidence in the value that the firm offers in the marketplace, and has to be challenged. In practice, you have a range of options for raising the achieved price:

•

The pricing ladder.

The basic price is low, but the extras add up. So your flight costs $5, but then there is the booking charge, the seat reservation charge, the luggage charge, the check-in charge, the inflight services charges, taxes and suddenly you have been charged a fortune for your “bargain” flight. You can see pricing ladders at work in the selling of PCs and cars, which always seem to come with costly but attractive extras.

•

The price anchor.

Set a very high nominal price, then discount heavily against it. This is how wine and furniture are always being sold at 40% or 50% discounts. The retailer establishes a high price expecting no sales at that level, then they offer a “bargain sale” where they sell their products at a good margin.

•

The bait and switch.

Offer a low introductory price and once the customer is hooked, revert to “normal” pricing. You see this in phone packages, but also in business-to-business where consultants and contractors may offer to do the specifications and initial work cheaply or even for free: by the time they have finished you are hooked and cannot escape.

•

The price jumble.

This is a variation on the pricing ladder. Make your pricing so complicated that anyone trying to compare packages loses the will to live: think of mobile phone deals. There will always be some element of the jumble you can highlight as being top value.

•

The unique package.

The more standardized your market becomes, the harder it is to raise prices. So seek differentiation. Change the size of your packaging; change the form of your product; change the service and terms. Be different, create multiple price points and choice.

•

Listen to sales person:

they always want a lower price.

•

Listen to customers:

they say they want a lower price, but often other things such as service are more important and they are prepared to pay for it.

•

Keep on discounting with special offers:

you will educate your customers only to buy when you are on special offer.

•

Think in terms of “the price”:

a single point pricing scheme is too simple for competitors to beat and for customers to compare. You need to be creative in how you price.

You can use research for three basic reasons:

•

Understand attitudes and behavior

Each requirement needs a different approach, as follows.

You can gain customer insight in plenty of ways:

•

Become a customer yourself

and endure the misery or delight your company creates. This is useful as a wake up call. But it is also dangerous. The

experience of one executive, especially the chief executive, should never be used to represent the experience of the market overall.

•

Co-create products with your customers.

Your heaviest users are very useful: they often find creative and original ways of using your product and can see many more ways in which your products and services can be improved. Involve them directly in helping design the next generation of your products and you will have a product or service which you know meets the needs of the market.

•

Commission focus groups.

These are powerful and often misused. Executives often ask, “What did the focus group prefer?” That is irrelevant. You are not looking for a statistically irrelevant conclusion from a group of eight customers. You are looking for the one insight about how they really think about you and your rivals, about how they use your product or service in practice, what annoys them most about the service, and what they would like instead. Given you are looking for insight, it is often worth listening to the entire focus group yourself: do not expect the moderator to hear what you need to hear.

This is the staple of many market researchers. Ask 1,000 people why they buy Ariel instead of Daz and then summarize the statistically significant conclusions. The problem with this is that customers will lie to you out of politeness and ignorance. They will say what they think they ought to say (“it was cheaper or better”) not what you need to hear (“bought it because my dog likes its smell...”). Attitudes are very dangerous.

If you can, focus on behavior. Find out how people buy, how people decide. Choice is not always rational. In theory, you bought that mobile phone package because it was the best overall deal. In practice, perhaps you became overwhelmed by the confusing choice and in the end you bought because you trusted the knowledgeable sales person who gave you a good story to tell your friends about what a good deal you got. And the phone looks cooler than your colleagues’. So should the phone firm focus on price and benefits (the result of looking at attitudes) or focus on in-store sales support and product design (result of focusing on behaviors)? You need both.

look for the outliers and distinct market segments

With this sort of research, ignore the averages. Look for the outliers and distinct market segments: this is where you can build a distinctive offering and, hopefully, build a competitive advantage over less differentiated rivals.

Tracking performance is basic housekeeping; for instance, consider:

• Market share

• Relative pricing

• Media spend versus competition

• Brand awareness, prompted and unprompted

This will not generate any great insight, unless you are doing a test market in one region which you want to compare with other regions. But if you fail to track it, you are leading the organization as blindly as if you had no financial information on performance.

You need to know about competition. Some, but not all of the answers are on Google. You need a little more work and creativity to find out exactly what you want to find out. Here are 10 ways you can find the answers.

Ten ways to find the answers

1. Google.

Yes, Google, Facebook and other online resources will be a mine of information. The job of the intelligence analyst is not to find some dark secret, but to put all the pieces of the jigsaw together and build the big picture. Dig for press releases, speeches by key executives, comment, industry analysis, and more.

2. Company accounts.

Companies are required to disclose more and more. Most people ignore the detailed findings because they are eye-wateringly boring. But in amidst all the routine rubbish there is always a rich vein of intelligence: mine that vein. And while you are doing this, you might ask their PR department to put you on their mailing list for the company newsletter, which will brag about their brilliant plans. Wonderful.

3. Planning, trademark, patent, and regulatory filings.

These give early warning of what your rivals intend to do. Make sure you have all of these filings tracked and analyzed on a regular basis.

4. Suppliers.

You probably share some of the same suppliers. They will get advance warning of new products and initiatives being planned because they will have to change what they sell to your competitor. They will be discreet, but try being nice to your supplier. You will be surprised what you can learn.

5. Customers.

You probably also share customers who are more than happy to provoke you by telling you how much better your competitor is than you are, and how that competitor is going to introduce an even better promotion or product next year. Take the abuse, even encourage it. You want to find out all you can about your rivals as early as possible. Let your shared customers be your early warning radar system.

6. Consultants.

They will never tell you that competitor X is doing Y. Instead they will show you an industry analysis which thinly disguises the same data. Or they will quote an industry example of best practice, which again will be your competitor thinly disguised. Let all the consultants show off their knowledge and learn from them.

7. Ex-employees.

Most industries are fairly incestuous and you will probably have hired a few employees from your rivals. Make sure you debrief new hires thoroughly: they probably know more than they realize, and will tell you more than they intend even if they think they are being discreet.

8. Industry sources.

Industry associations have plenty of information: use it. Brokers do industry and company analysis: they need to be nice to you, so make sure you get early copies of all of their reports. Be creative about industry sources. Media associations will tell you how much is being spent on different sorts of media by your industry: from there you can work out whether you are investing more or less than the competition.

9. Mystery shoppers.

Buy your rivals’ products and services. Experience what they are really like. And do not buy your own products and services through the special company scheme, because you will never endure the frustration and anger your firm forces onto your customers.

10. Market research.

Most markets are already well researched. If necessary, commission some market research to find out what your customers really think of your rivals and why they do or do not use them.

If this sort of information is important on a regular basis, create a small competitive intelligence unit which can gather together all the titbits of information from sales people, buyers, customers, the media, and regulatory sources. Let them build the complete picture for you.

If you hire consultants at vast expense to do a deep industry and competitor analysis, they will give you the results of the 10 searches above. Most of them you can do yourself at no cost. A few of them require modest spending on market research or regulatory tracking. If you learn to do it yourself, you can keep yourself constantly up-to-date with your competitive intelligence, instead of relying on occasional and expensive ad hoc analysis by consulting firms.

If you want to market your product or service, it helps to know why people buy. What you think you sell and what people hope to buy may not be the same thing.

Your product or service works at three levels for the customer:

• Features

• Benefits

• Hopes and dreams

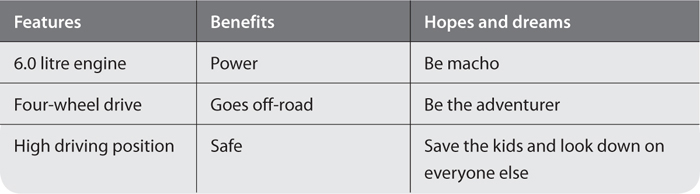

Some highly simplified examples will make the point. First, off-road cars. They are curious because the vast majority rarely, if ever, go off-road. They are city cars. So the main benefit of the car (going off-road) seems pointless, until you look at what the manufacturers advertise. They advertise a dream, a self-image which appeals to a certain sort of city dweller.

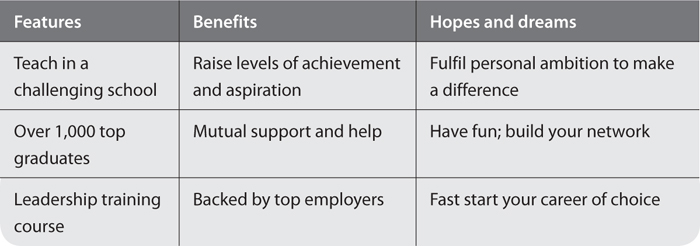

Second, a graduate recruiting proposition. Teach First attracts top graduates (over 7% of Oxford and Cambridge graduates apply every year) to teach in tough schools for two years for half the salary and twice the grief of working in a bank or consulting firm. So why does it work?

As a manager, the fatal trap is to fall in love with your own product. We get so excited about the amazing features of our product that we lose sight of what the customer is looking for. Even cleaning products have hopes and dreams, about being house proud. Selling Fairy Liquid in Scotland, I found working class homes all put their bottle of Fairy Liquid on a shelf in the kitchen window, where everyone could see it. Bizarre Scottish habit? No. Fairy Liquid is the premium detergent, and so it was a simple way of saying, for a few pennies extra, that the home maker had high standards and was house proud. The families with own label detergent carefully hid their product away in a kitchen cupboard, to avoid the shame of being seen to be penny pinchers.