The Modern Middle East (55 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

Because Lebanon has historically found itself in the firing line of much more powerful rivals—the Israelis, the Palestinians, the Syrians, and more recently the Iranians—its domestic politics has been shaped, perhaps more so than those of any other regional state, by international crosscurrents over which it has had little or no control. Repeatedly, Lebanon’s various

factions have failed to demonstrate their own resolve to sustain the country’s constitutionally democratic political system. But the constant machinations of overbearing, external players have done even more harm to the consolidation of a consolidated democracy. Although the Taʾif Accord mandated the departure of Syrian troops from Lebanon, who had been present since 1976, it was not until April 2005 that the Syrian army finally withdrew from the country. Up until that point, “Damascus essentially controlled Lebanon—dominating government, interfering in elections, naming presidents and prime ministers, making major policy decisions.”

105

Syria’s withdrawal was prompted by Hariri’s assassination the previous February, once again plunging Lebanon into chaos and leading to bitter acrimony among the country’s multiple factions. The animosities were temporarily set aside in the aftermath of Israel’s devastating war on the country in 2006 but resurfaced again shortly thereafter. Iran, meanwhile, found in its ally the Hezbollah a highly effective deterrent against possible Israeli attacks on its soil.

On the one hand, Lebanon’s various factions are too divided and acrimonious to enter into lasting, viable alliances. On the other hand, none is strong or numerous enough to effectively overwhelm the others and impose its will on them. Not surprisingly, early on in the life of the republic a consociational democracy was determined to be the most appropriate form of political system for the country.

106

But neither the Lebanese elites themselves nor the external actors interested in the country have done much to make the system meaningfully effective. If anything, they have often deliberately eroded its efficacy. Nevertheless, despite its chronic precarious balance, at times teetering on the edge of collapse, the political system has somehow withstood the test of time since the civil war ended. How much more meaningfully democratic it will become over time is yet to be determined.

As the examples of Iran, Morocco, and Lebanon show, up until the 2011 uprisings, the pace, depth, and meaningfulness of liberalization processes in the Middle East all were a product of the agendas, priorities, and overall nature of dynamics within the state. Iran offers a paradigmatic example of a stateled transition arising from tensions between “hard-liners” and “soft-liners.” These internal tensions are far less apparent in Morocco, where the state remains far more cohesive in its goals and priorities, so the transition process there has been considerably slower and far more controlled. In Lebanon, the ruling elite’s commitment to the spirit of the Taʾif Accord has proven paramount in maintaining the overall vibrancy of the country’s democracy. Up until the late 1990s the locus of the elites’ commitment lay elsewhere. The election of a new president in 1999 and the slow emergence of a new cadre of politicians appear to have brightened the prospects for

Lebanon’s democracy.

107

The degree to which society eventually becomes involved in the transition process and the timing of such involvement depend on specific conditions within each country. The frequency of political mobilization in Iran over the past two decades appears to have been instrumental in giving Iran’s transition until 2009 greater societal resonance, whereas a history of statist absolutism has made most Moroccans take a wait-and-see attitude toward the state’s proclaimed championing of democracy. In Lebanon, where sectarian and community leaders have long held sway among their respective clients, the popular scope of the country’s democracy has been defined more sharply by elite agendas and priorities.

As these cases demonstrate, until 2011, across the Middle East states resorted to a variety of means to ensure their uncontested control over the political process and the nature of political input by social actors. In almost all cases this was done through the legislative organs of the state, which in dictatorships served as “instruments of cooption” and enabled dictators to make policy compromises and concessions.

108

They helped with “controlled bargaining” and enabled the dictator to “reconstitute his bargaining partner each time.”

109

In Yemen, for example, these formal venues for dissent helped boost the Saleh regime’s appearance of legitimacy both domestically and internationally and created safety valves for pressures from below by providing avenues to the expression of oppositional sentiments, however mild and sanitized.

110

But parliamentary elections were not always as easy to manage, opening the possibility that they might be undermanaged, as was the case with the Egyptian parliamentary elections of 2005, or overmanaged, as with Egypt’s 2010 parliamentary elections.

111

In fact, the farcical nature of Egypt’s 2010 elections directly contributed to the spontaneous demonstrations that erupted the following January and led to the fall of the Mubarak regime.

112

THE 2011 UPRISINGS

Such was the state of Middle Eastern politics at the dawn of the new millennium. Repressive authoritarianism prevailed across the region. As early as the 1970s and the 1980s, little was left of the ruling bargain that Nasser had devised, with state services across the region deteriorating, the states incapable of delivering many of their assumed functions, and all but a few of the wealthiest suffering. Much-hyped liberalization programs had come to nothing. Fear reigned supreme. Authoritarian regimes seemed firmly entrenched and immovable.

This seeming stability of authoritarian regimes masked “deep structural changes in the public sphere” that had been under way for some time.

113

Far from becoming autonomous, states became dependent on the social classes for their continued acquiescence to the ruling bargain, with any attempt on the part of the state to renegotiate the bargain’s terms by reducing its patronage provoking sharp reactions from those affected. This made the introduction of economic reforms extremely difficult.

114

Few states had the political capital to demand tough economic concessions from their peoples, so they had to persevere in defeatist economic policies. But the regime’s old remedies no longer sufficed in beating down the public. “Economic woes escalated, the middle class disappeared, the poor scrambled for survival, and youth found all doors closed to them. Sectarian and tribal conflicts broke out unpredictably. Labor strikes intensified and proliferated.”

115

What was needed was only a spark to set the entire region on fire. That spark came from Tunisia in late 2010.

Events in the small town of Sidi Buzid in Tunisia showed that besides fear and repression there was little that the Ben Ali dictatorship—and by implication other dictatorships in the region—relied on. They also showed that once the fear barrier had been breached, once people felt they had little to lose and much to gain from overcoming their fear of regime repression, little could stop them from pressing all the way for the regime’s overthrow. Before long, the protests spread from Sidi Buzid to Tunis and Sfax, the country’s second-largest city, and on to Cairo, Alexandria, Ismailia, and elsewhere in Egypt, as well as Benghazi and Tripoli. Soon much of the Middle East was in revolt.

Common themes emerged during the protests, with most Fridays declared as days of rage across the region. Protesters imitated each other’s tactics, such as the seizing and holding of public squares or the uploading of protest videos on YouTube. A powerful Pan-Arabist outlook emerged among the protesters. “Protestors in Yemen or Morocco hung on every twist in Bahrain, while Syrians eyed the violence that met the Libyan challenge.” The protesters adopted identical slogans, and terms such as

baltagiya,

used in Egypt to refer to regime thugs, came into widespread use all across the region.

116

As the crises were deepening, presidents, mocking the protesters, gave speeches denouncing the demonstrators as stooges of outside powers, in the process making themselves sound “arrogant, patronizing, hypocritical, and just plain stupid.”

117

Their concessions, when offered, were too little, too late. Mubarak’s promises of genuine reforms for the first time after nearly thirty years in office rang hollow. Qaddafi, calling the protesters “rats” and himself a “revolutionary from the tent, from the desert,” only egged on more Libyans to join the rebellion. And Bashar Assad’s describing the rebellious Syrians as treasonous lackeys of foreign powers only encouraged more of his countrymen to join the movement to oust him.

118

What

made the cross-national movements of January 2011 different was the success of the protests, the backfiring of traditional repressive regime responses, and the framing of regionwide protests into “a single coherent regional narrative” on Al-Jazeera and on social media.

119

This was particularly the case with the January 25, 2011, protests in Egypt, which “convinced the world that the protests marked something fundamentally new.”

120

Before long, dismissive regimes realized that they were facing genuine threats.

121

Initially, all of the uprisings began as spontaneous acts of defiance and rebellion against dictatorial regimes. The demonstrations started out as small gatherings of street protesters who were motivated not by specific ideologies but by a simple desire to effect political change. They quickly grew in size and spread like wildfire, from one city to another and from one country to the next. In Tunisia, following Mohammed Bouazizi’s self-immolation on December 17, 2010, street protests dramatically grew in numbers and quickly turned violent, resulting in scores of deaths across the country. By early January, with his support system crumbling, Ben Ali was left with few options but to rely almost exclusively on his military commanders to crush the protests. When on January 13 his offer of major concessions in a nationally televised speech failed to stem the tide of the protests, the military refused his order to fire on the protesters. The next day, after some twenty-three years in office, he fled the country and found exile in Saudi Arabia.

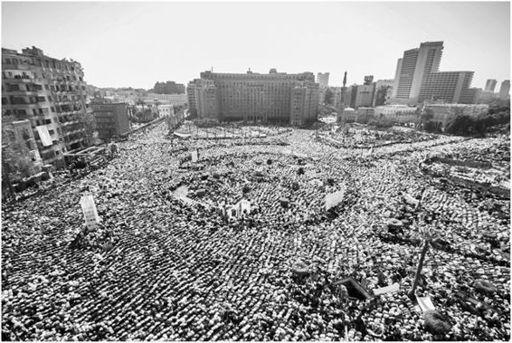

A similar pattern unfolded in Egypt, where on January 25, 2011, protesters gathered in Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square to demand an end to Mubarak’s thirty-year rule. For the next eighteen days, Egypt was the scene of mass demonstrations unfolding at the same time as the regime sought in feeble ways to hang on to power and to break the demonstrators’ will. As in the Tunisian case, the Egyptian government tried a mix of unprecedented concessions and brutal repression to stop the spreading demonstrations and to retain power. In what must have been one of the most shortsighted and idiotic moves to quell the demonstrations, government-sponsored thugs, the

baltagiya,

charged through demonstrators on horseback and with camels in what came to be known as the “battle of the camel.” But by now the revolution was all but unstoppable. After eighteen days of nationwide protests, Mubarak finally stepped down on February 11, 2011, amid scenes of mass jubilation and transferred authority to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, SCAF. The SCAF was composed of twenty-one senior officers of the Egyptian military and was headed by Mubarak’s longtime defense minister, Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawi. The Egyptian military began seeing itself as the guardian of the transition, in fact considering the transition as an opportunity to enhance its own political stature

and economic fortunes in a post-Mubarak era.

122

After nearly fifteen months of rule by the SCAF, presidential elections were held in May and June 2012, with the candidate from the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, Mohamed Morsi, narrowly beating out his opponent, Mubarak’s last prime minister. Morsi formally assumed the presidency of Egypt on June 30, 2012.

Figure 22.

Protesters at Friday prayers in Tahrir Square in the first protest after the fall of Hosni Mubarak. Getty Images.