The Moneyless Man (11 page)

Authors: Mark Boyle

My only frustration, I suppose, was that people around me hadn’t, understandably, really grown to appreciate how much more demanding this life was, both of my energy and my time. They expected me to live the fast life alongside my slow life, go to meetings in the city two or three times a week and do all the things I had to do. Sometimes I wished they could swap places with me just for a couple of days. But I had made my bed; there was no point moaning about the state of the sheets.

CHRISTMAS WITHOUT MONEY

Christmas began as the celebration of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, a man who, by historical accounts, spent the last years of his life preaching simplicity. And to some people it still is. However, for the majority of people in western society, what it has become is far removed from what it was originally. The festive period has now become the most important shopping time of the year for most retailers. According to Deloitte, in 2008 the average Briton spent £655 on gifts, socializing and food. That’s over £36 billion for the nation – and 39% of it was on credit. UN figures show that during the twelve days of Christmas 2008, worldwide, 207,360 kids (the equivalent of the population of a small city) died of starvation.

What was traditionally a time to relax with family and friends has gradually become a huge source of stress for many people. The American Psychiatric Association estimates that between 10% and 20% of Americans suffer from Seasonal Depression, with

a 10% increase soon after Christmas, most of it due to the financial hangover of its aftermath. It’s an expensive party in more ways than one.

Given the amount of pressure, subtly applied through huge advertising campaigns, to buy the biggest and best Christmas presents for your family and friends, many people questioned the rationale of becoming moneyless at the exact point of the year when it seems everyone else can’t spend enough. It did feel a bit strange, but to be honest, not buying presents didn’t really bother me; my adult friends knew what I was up to and weren’t expecting anything. And I think the fact I demanded they buy me nothing in their turn reassured them I wasn’t playing Scrooge. I was concerned about my nephews, but I decided it would be a good chance to explain to them why Uncle Mark wasn’t as kind and generous as Santa Claus (who, for a guy that travels the world using a reindeer and sledge, sure has one hell of a carbon footprint).

What did bother me was the thought of not getting home to spend Christmas with the people I love. The family had gone to relatives’ houses almost every year I could remember and my folks loved having us together for Christmas. Did leading what I deemed to be an ethical life mean I would have to upset my mother?

My main hope stemmed from a phone call I’d received from a television show in Ireland on the first crazy day of my year. They wanted me to come and be interviewed on a daytime lifestyle show,

Seoige

, presented by Gráinne Seoige, voted Ireland’s sexiest woman. This was upmarket bartering. Guests were usually paid quite handsomely for their ten minutes of work, but this wasn’t an option for me, so I politely declined. They also offered me return flights and trains and buses in between. In 2006, I’d vowed to never fly again, so I told them that if it did happen, I would only go by ferry. And as one of my principles was to accept only as

much as I needed in life and no more, I felt that even a train or bus ticket would have been too much.

For most of December,

Seoige

was merely a possibility. My other idea was to cycle to Fishguard (my nearest ferry terminal for Ireland), hitch a ride with a truck driver and cycle all the way to the northwest. But few truck drivers take hitchhikers now, because of insurance complications. The more I contemplated this option, the harder it seemed. Doing it with money would be hard enough; without money it would be perilous at this time of year.

Christmas approached and I had no concrete solution to getting home to my folks. I was increasingly frustrated with the limits that living this way was putting on me. But just when I thought it wasn’t going to happen, I got a call from RTE to say they wanted me on the show and would email me round trip tickets. This was the solution to my only real obstacle – getting across the Irish Sea. Everything else I was fairly confident I could pull off without money, but the Irish Sea is a long swim. I decided to hitch the whole road trip, from Bristol to the northwest of Ireland. If I was lucky, it would take me two days; if not, Christmas Day would probably see me walking up a deserted main road, without food or shelter. I wouldn’t even have a working phone; without credit, I couldn’t receive calls outside the UK.

I didn’t have a lot of time to prepare. Food was the main issue; I decided I’d better collect and make enough for three days. You never know how long hitchhiking is going to take – sometimes you can wait hours (though that has never happened to me). It was only about a four hour journey to Fishguard, but I knew I needed to get there before sunset, which would be at about 4.30pm. Getting a lift in the dark is difficult and sometimes a bit dangerous, depending on what type of road you’re dropped off on. Sometimes you can get dropped off at the wrong end of a

city. That was my worst case; it would have meant walking for miles, with a heavy backpack and without a map, to get to the next hitching point.

I started in good time on December 23, leaving at 10.30 in the morning to catch the ferry from Fishguard at two o’clock the following morning. Starting my journey the day before Christmas Eve was an interesting experiment. Before setting off, I wondered whether the Christmas spirit of old would prevail. Would everyone who saw me want to help me on my way or would they be too stressed and busy even to a see a hitchhiker on the side of the road?

My hitchhiking experience tells me that you have to get into the right head space. When your body language portrays confidence, openness, optimism and happiness, getting a ride seems like child’s play. When you’re a bit depressed, it feels like no one wants to know. I got into the groove, got smiling and got out on the road. This wasn’t hard, as I love the adventure of hitchhiking. On the bus or train you know that you’ll get on at A and get off at B and rarely speak to anyone in between; hitchhiking, you never know what is going to happen. If you can get over the uncertainty, it really puts the excitement back into travel.

TIPS FOR HITCHHIKING

Location, location, location. A great spot makes the difference between waiting five minutes and waiting two hours. Find a place where you can be seen easily, where the traffic is moving at less than 45 miles an hour and where a car has enough time and space to pull in safely. No driver will risk their life to pick you up.

Look happy. Few people want to share their car with someone who looks miserable! Smile and be friendly.

Wear some bright clothing. It also helps if you look clean and approachable. Have clothes to match all sorts of weather.

Keep luggage to a minimum.

Know your route. Know the roads you want to take and avoid freeways; it’s illegal and difficult to hitchhike on them in most countries. Some people like to use a sign to show their destination but I don’t bother.

Trust your instincts. If you have a nervous feeling about getting into a car with someone, make a polite excuse and don’t. But don’t be too fearful – I’ve hitchhiked since I was a kid and never once had a problem, although there are issues to consider regarding your gender.

Don’t feel down. Don’t let cars going past get you down and don’t criticize the drivers who do. A positive attitude is vital to get you where you want to go!

In many respects, hitchhiking is a good metaphor for life!

My positive mental attitude seemed to work and I made it to Fishguard in less than five hours, not much longer than if I’d driven myself. However, this did leave me with about twelve hours to pass in an empty ferry terminal. As I sat there, alone, I wondered how busy the airport was and what impact cheap flights have had on ferries. The good news was that I had half a day to read in silence, something I crave. The bad news was that it was very cold. There was a television room, in which the heating automatically went on as you walked through the door. But I was the only one there, and my self-imposed rules said I couldn’t go in, because the heaters would be on just for me. I spent the entire day glancing at the door, knowing only too well

that if I went in my body could thaw out. Moments like this made me wonder if I was taking things too far; then I visualized the sea-levels rising over low-lying countries such as the Maldives, and went back to reading my book.

A terminal attendant came to tell me about this warm room and even went in to turn the television on. When I stayed where I was and he asked why, I didn’t know what to say. If I told him the real reason – that I wasn’t going in because of climate change – would he have thought me insane or would he have respected my views? Arrogantly, I didn’t give him the chance, but muttered that I was really comfortable where I was, though I appreciated his offer. He left, looking at me curiously. Around midnight, another passenger arrived and headed straight for this room of luxury. The sound of ten electric heaters turning on and my footsteps aiming in that direction quickly followed each other; I convinced myself that if the heating was going on anyway, I may as well make the most of it.

I got about thirty minutes’ sleep on the three-and-a-half-hour journey to Rosslare. On the ferry, I had some problems with drinking water. I’d assumed I would be able to get some water either from the bar or in the bathroom, so hadn’t bothered filling up my bottle. That was a false assumption; one of the restaurant cooks warned me that the tap water was far from drinkable, pumped full of chemicals to make it clean. I’d lived on a boat, so I should have remembered this. Already slightly dehydrated, I had to start hitching without water, knowing that it could be at least five hours before I could find somewhere I could refill my bottle.

It was Christmas Eve and I had about twelve hours to get from the most south-easterly point of Ireland to the very north-western coast; roughly three hundred miles. On the freeway, the route most long-distance drivers would use, this would normally take about six and a half hours. The problem was I couldn’t risk taking the freeway route. It’s illegal to hitchhike on a freeway; you

can’t get dropped off on them and the on-ramps are always hit and miss. So I had to go on the smaller roads, which meant I would have to get a lot of short rides.

I hightailed it out of the ferry port to try to get ahead of the cars and ended up running for over a mile to get to a good spot. Rosslare is a very quiet town – whenever the cars get off the ferries and leave, nothing much else passes through. My ferry was the last one before Christmas; if I missed the traffic coming off it, I was in trouble. But my luck was in; a truck driver took me a few miles up the road to a great location and I was off. And that luck continued all day – the longest I waited for any ride was about ten minutes.

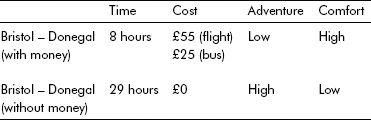

By 3.30pm I was knocking on the door of my folks’ house, to the complete surprise of my mom, who thought I hadn’t a hope of making it the whole way before Christmas. It had taken me just under nine hours to get from Rosslare, about the same as if I’d had my own car and taken a couple of breaks. Humanity, it seemed, has a really positive side that we don’t hear about too often. Between Bristol and Donegal, Ireland, I had fifteen hitches altogether. Compared to a cheap flight, the results were varied.

This table tells a story in itself – have we as a species swapped adventure for convenience?

It was really fascinating to see the types of people who gave me a ride. Every one of them had an average car, which made me

question whether the more wealth you accumulated, the less you wanted to share. Most of the people who gave me a ride said that they had hitchhiked when they were younger, so there was a definite empathy. From their stories, I could tell that some of them wished they were back on the road and feeling the adventure of hitchhiking again; in some cases it almost felt like owning a car was something inflicted on them. Although there was only one person in the car every time, they were a very diverse group. Contrary to popular opinion, the majority were women (about three out of every four rides I receive are from women). One, who had just come off the night shift and faced a fifty-mile drive home, told me she always picked up hitchhikers whenever she saw them, just to keep herself awake, and in ten years had never once had a problem.

One incident, which really uplifted me, came after I had got out of a car only to realize I’d left my freshly filled water bottle behind. This was my only water container and I hadn’t drunk much for twelve hours. Without it, I would have had to search in a trash can for an old plastic one and fill it in a bathroom somewhere. One hour, and another hitch later, the guy in whose car I’d left the water bottle pulled up. He’d spent forty minutes searching for me so he could give me my bottle back. I’d told him I was living without money and he guessed the bottle was pretty important to me. This guy had told me he had just spent two years in prison after a fight outside a nightclub. And here he was, going to all lengths to make sure a complete stranger had his water bottle. This reinforced my belief that there is no such thing as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ person; each of us is just as capable of huge acts of kindness and generosity as we are of causing harm. Our challenge, as evolving humans, is to maximize the former and minimize the latter.