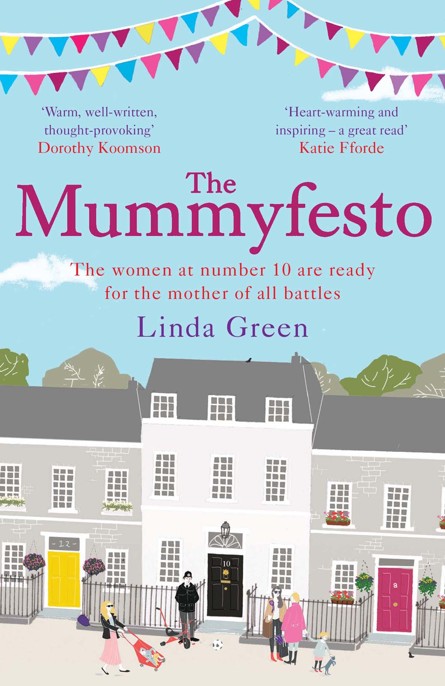

The Mummyfesto

Authors: Linda Green

MUMMYFESTO

Linda Green

First published in 2013 by

Quercus

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2013 Linda Green

The moral right of Linda Green to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

PB ISBN 978 1 78087 522 4

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78087 523 1

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Praise for Linda Green

‘Smart, witty writing’

ELLE

‘One of the most touching books I think I

will ever read. A triumph’

Chicklit Reviews

‘Witty and funny’

Company Magazine

‘Laugh-out-loud funny’

Reveal Magazine

‘Utterly riveting’

Closer

‘Linda has a great writing style which is almost

effortless but be prepared to laugh and cry’

LoveReading.co.uk

Also by Linda Green

And Then It Happened

Things I Wish I’d Known

10 Reasons Not to Fall in Love

I Did a Bad Thing

The Resolution (short story)

Linda Green is an award-winning journalist and has written for the

Guardian

, the

Independent on Sunday

and the

Big Issue

. Linda lives in West Yorkshire.

The Mummyfesto

is her fifth novel.

For Rohan

‘If you don’t like the way the world is, you change it.

You have an obligation to change it.

You just do it one step at a time.’

Marian Wright Edelman

SAM

‘Mummy, watch how fast I can go.’

I had this crazy, outlandish dream, well, more of a fantasy really, that one day we would arrive at school not just on time but actually early, maybe even by as much as five minutes. As I watched Oscar career along the canal towpath, totally oblivious to the mound of dog poo he was fast approaching, I realised that this was not going to be the day that happened.

‘Oscar. Stop. Now.’

It was too late.

‘Mummy,’ called Zach, who was a few paces ahead of Oscar but had turned to see what all the commotion was about, ‘Oscar’s gone straight through that pile of dog poo.’ He said it with an air of fascination and awe rather than any hint of trying to get his little brother into trouble.

Oscar looked down and wrinkled his nose. ‘Urrgghh,’ he said, ‘I’m going to be the smelliest boy in school today.’

‘No you’re not, Oscar,’ I said, at last catching up with them and surveying the wheels of his powerchair, ‘because we’re going to get you cleaned up right now.’

‘Are you going to take me through the carwash, Mummy?’ asked Oscar. ‘Please, can you take me through the carwash?’

I smiled down at him, resisting the temptation to ruffle his hair in case he insisted on redoing the gel and prolonging the delay even further.

‘No, love. I don’t want you getting squished in the rollers. It’s going to be good old-fashioned elbow-grease, I’m afraid.’

‘Why are your elbows greasy?’ asked Oscar. There was no time to try to explain.

‘Zach, stay here with Oscar. Don’t let him go anywhere or do anything he shouldn’t do. Oscar, do what your brother says and I’ll be straight back, OK?’

I ran back down the towpath. It was the sort of occasion when I was grateful I was not one of those pristine power-dressing mums who totter to school in their stilettos (not that we had many of those in Hebden Bridge). Say what you like about Doc Martens, they are bloody good for legging it down muddy towpaths during a school-run emergency.

It was not the first time I’d had to abandon my children and run home. Usually it was a forgotten book bag, packed lunch, PE kit or something for show and tell. But nor was the powerchair-meets-dog-poo situation entirely

new to us. Which explained why there was a plastic container in the toolshed in the front yard marked ‘poo’ (as opposed to the one next to it marked ‘punctures’), which contained a scrubbing brush and a mini-bottle of washing-up liquid.

I grabbed the watering can, which was half full with rainwater (one of the good things about living in the Pennines) and set off back down the towpath.

When I arrived, Oscar looked at the watering can and back to me, rolled his eyes and said, ‘Mummy, I am not a sunflower, you can’t water me to make me grow.’

Zach laughed obligingly, knowing full well, as I did, that Oscar understood precisely what the watering can was for and only said it to get a laugh. I winked at Zach, held the watering can over Oscar’s head for a second to make him squeal before I sprinkled it on the wheels of his powerchair and attacked it with the scrubbing brush and washing-up liquid.

Miraculously, we still made it through town and up the hill in time to see the last few stragglers heading through the main doors into school.

‘Come on, Mummy,’ called Oscar over his shoulder as he whizzed up the road in front of me. I joked sometimes that the reason we chose this school in preference to the nearer one was that I knew the school run would keep me fit. It wasn’t the real reason, of course. We chose it because we thought it was right for Zach and, very importantly, that it would also be right for Oscar. Everything always had to be right for Oscar.

Shirley the lollipop lady bent to talk to Oscar who threw his arms around her in his customary greeting. It was only when I finally caught up with them and Shirley stood up that I noticed the tears in her eyes.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked.

‘I knew it,’ she said. ‘I managed to keep myself together for other kids but second I saw your Oscar that were it.’ She sniffed and wiped her nose with her hand before managing a watery grin at Zach.

‘What’s happened?’ I asked.

‘Just been given me notice by council. Doing away with me they are. Me and half a dozen others.’

‘But they can’t. That’s ridiculous. This is such a busy road.’

‘Bean-counters in suits, that’s all they are. Don’t give a toss about kids, all they’re bothered about is cutting budget.’

‘What’s Shirley saying?’ asked Zach. ‘Why is she crying?’

I crouched down to Zach’s level and put an arm around him and Oscar.

‘The council are trying to take Shirley’s job away,’ I told them. ‘They’re trying to save some money.’

‘But we need Shirley,’ said Zach. ‘She keeps us safe.’

‘She stops us getting run over by lorries and splatted flat on the ground,’ added Oscar. Letting him renew

Flat Stanley

from the library twenty-four times had obviously been a bad idea.

‘Council bigwigs don’t know you kiddies, see,’ said Shirley. ‘They don’t realise how important you all are.’

‘We’ll write to them and tell them,’ said Zach.

‘But we’ll say please,’ pointed out Oscar. ‘So they don’t think we’re being rude.’

They both looked up at me. It scared me sometimes. How trusting they were that those in charge would always be fair and just. I wasn’t sure when I would sit down with them and explain that it didn’t always work like that in the big bad world out there. All I knew was that I wasn’t ready to do it just yet.

‘Yes and we’ll start a petition,’ I told them. ‘Get all your friends and their mummies and daddies to sign it. To say we need Shirley to keep you all safe.’

‘Can I write a bit about not wanting to get splatted flat by a lorry?’ asked Oscar.

‘You can if you like, love.’ I smiled.

Shirley sniffed and held up her lollipop. A white transit van drew to a halt and she ushered us across.

‘We’re going to fight this,’ I told her, squeezing the hand which wasn’t holding the lollipop. ‘We’re not going to let them do this, don’t you worry.’

We hurried across to the playground. I kissed Zach and Oscar, distributed the correct book bags and lunch bags and waved them off with instructions to apologise to their teachers for being late.

‘Can I tell Mrs Carter about the dog poo?’ asked Oscar.

‘If you must,’ I said, shaking my head and hoping the description wouldn’t be too graphic, though the memory of his detailed account of the time another child was sick in the swimming pool led me to suspect otherwise.

I actually managed to leave work on time for a change that afternoon. I was keen to get back to school to talk to other parents before the children came out. Anna was the first one I saw. Anna was always early. She had a phone which beeped to remind her to leave for school in plenty of time. And she had the advantage of working from home on Mondays.

‘Shirley’s being made redundant,’ I blurted out to Anna.

‘Hello, Sam,’ she said, reminding me that I had forgotten to do the pleasantries. ‘Who’s Shirley?’

‘You know, Shirley. The lollipop lady.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Anna said. I took it she didn’t know Shirley as well as we did, what with her living on the right side of the road. ‘Well, that’s outrageous.’

‘I know. She told me this morning, in tears she was, poor thing. I said we’d do a petition. That we’d fight it all the way.’

‘Of course we will. I’m surprised you didn’t know about it, though. You’d think they’d consult the governors.’

‘Obviously not. I spoke to Mrs Cuthbert on the phone and she only found out this morning. We’re going to have a governors’ meeting next week, but in the meantime I’ve run this off. Tell me what you think.’

I handed her the petition form I’d printed out.

Anna read it, nodding as she went. ‘Seems fine to me.’

‘Good. Because I’ve printed a couple of dozen off already. I thought we’d better get started as soon as possible. You don’t mind do you?’

Anna looked at me, a slightly bewildered expression on

her face, as I produced a clipboard with several copies of the form attached from my shopping bag and handed it to her.

‘You don’t hang about do you?’ She smiled.

‘Well, no. The council are voting on this in a couple of weeks. We need to get started.’

‘Started on what?’ asked Jackie, collapsing on the wall beside us and immediately removing a pair of red platform shoes which were so unsuitable for walking up the hill, let alone being on your feet all day teaching, that they took my breath away.

‘We’re starting a petition,’ I told her.

‘Who’s we?’ she asked.

‘Er, me, Anna, you, I guess.’

‘Great, count me in. Where do I sign?’

‘You haven’t asked what it’s against yet,’ I pointed out.

‘I guess I’m just a born rebel,’ she said, taking a clipboard and pen from me and beginning to read. ‘Jesus, they can’t do this,’ she said a moment later.