The Mystery of Olga Chekhova (33 page)

Read The Mystery of Olga Chekhova Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #History, #General, #World, #Europe, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century

The inter-regnum which followed was uneasy, mainly because the inner circle of the Politburo was nervous, and with good reason. Lavrenty Beria seized back control of Soviet intelligence and security. They knew that he was not just powerful because of his position, he was also the most energetic and intelligent of them all. And Beria, they soon discovered, had a master plan. He wanted to end the Cold War through the reunification of Germany in return for massive aid to the Soviet Union from the United States. It may seem ironic that the most feared name of the Soviet system should have wanted to do this. Yet Beria, although never one of nature’s democrats, was at least a pragmatist. He knew that the Soviet Union could not catch up and beat the West economically through heavy-handed autarchy.

Beria first needed to sound out the West’s likely reaction through unofficial channels. He called on Prince Janusz Radziwill again and warned him to prepare to visit the United States, acting as his personal emissary. He also decided to find out what leading West Germans would feel by using Olga Chekhova. But Soviet intelligence still ‘over-estimated the importance of Olga Chekhova in both the cultural and political life in Germany’. In June, Beria summoned the head of the KGB German Department, Colonel of State Security Zoya Ivanovna Rybkina, who had been Zarah Leander’s controller during the war. She was instructed to fly to Berlin to meet Olga Chekhova and brief her on her task. On 17 June, East German workers rioted. Red Army tanks were ordered in to suppress the revolt. Beria, despite the alarm sown among his colleagues by events in Germany, decided to press ahead with his plan.

On 26 June, Rybkina met Olga Chekhova in East Berlin. We have no idea whether any of the Western intelligence services had their eye on Olga Chekhova and became aware of this meeting. In any case, the whole project was doomed for a very different reason. That very morning in the Kremlin, on Nikita Khrushchev’s instructions, several senior officers, armed with pistols and led by Marshal Zhukov, burst into a meeting and arrested Beria. The plan to reunify Germany had been denounced by his rivals as ‘a direct capitulation to imperialism’.

Olga Chekhova must have slipped back into West Berlin unnoticed. Rybkina, meanwhile, was the one in greatest danger. Khrushchev, who had some idea of what was afoot, wasted no time. He ordered General Grechko, who was in Berlin with a ‘special commission’, to investigate KGB activities there. Officers at the headquarters at Karlshorst were interrogated to find out if anybody from Moscow Centre had turned up in the city.

Rybkina was saved by one of Grechko’s GRU military intelligence officers whom she had known during the war. He helped her on to a plane back to Moscow while other KGB personnel loyal to Beria were rounded up. The purge was even more thorough in Moscow. General Sudoplatov, who had worked closely with Beria during the war, was sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment on one of the usual trumped-up charges. Many others of more junior rank suffered too. Lev’s former liaison officer during the battle for Moscow, Zoya Zarubina, was thrown out of the KGB simply for having been one of Sudoplatov’s group. Rybkina also had to leave the KGB. She was sent as part of the Gulag labour camp administration to Kolyma in the far north-east of Siberia.

To the astonishment of her chief in the KGB, she made no protest. ‘Do you realize where you are going?’ he asked. ‘Yes, I do,’ she replied. She went to Kolyma and spent two years there. She tried to help those prisoners whom she knew. She even met a German there, a prisoner whom she had met before the war, when he came to Moscow with a German opera group.

Mariya Garikovna also suffered, as another member of Soviet intelligence closely associated with Beria. She was thrown out of the KGB and could not get another job. It was, of course, a small hardship in comparison to what would have happened to her a dozen years before, but she found herself reduced to poverty for the first time in her life. According to her nephew, she was down to a single set of underwear, which she washed each night and dried on the radiator. This penury continued for several years until suddenly a new intelligence regime realized that her linguistic gifts were wasted. She was recalled for foreign service, mainly in Western Europe. It seems as if she was now acting as an ‘archangel’ to delegations sent on cultural and economic missions abroad. This was a sad waste of her talents, but that was a common fate. Even sadder was the manner of her death. Before a trip to Paris, she underwent plastic surgery on her face. In the Soviet Union such rarely practised techniques were crude to say the least. Mariya Garikovna died the following day from unforeseen complications.

Of the younger Chekhovian circle of cousins from Moscow in 1914, one of the first to die was Misha Chekhov. Aunt Olya showed Sergei Chekhov, who had almost worshipped him, a copy of an American newspaper dated 30 September 1955. It announced that the actor Mikhail Chekhov had died in Beverly Hills. Misha, the anointed of Stanislavsky, had been the ‘Method’ guru to many actors, including Gregory Peck and Marilyn Monroe. Aged just sixty-four, he had looked much older than his years. Sergei felt, as perhaps Misha did himself, that he had never sustained the brilliant promise of his days with the Moscow Art Theatre as Hamlet, Erik XIV, Malvolio and Gogol’s Government Inspector. Did the genius simply wither, once separated from his Motherland, or did he burn himself out with alcohol?

Misha’s former wife, Olga, on the other hand, never seemed to burn out, partly because she was a strong pragmatist. Unlike Misha, she never allowed herself to suffer the disillusionment of dashed ideals. Misha himself had been her only ideal, and she was probably grateful in retrospect for the harsh lesson of their failed marriage.

She knew that her profession had increasingly little to offer a woman of her age, but she was determined not to give in. Her slightly raffish and voluptuous elegance had served her well in so many movie roles, but she knew those days were past. She would try other roles more suited to her fifties. To take advantage of the great appetite for the cinema in West Germany during those hard years before the economic miracle, she even set up her own film production company, ‘Venus-Film München/Berlin’. Olga made contact with the new Communist regime at the old UFA studios at Babelsberg to attempt co-productions and to sell her films to East Germany. Her big mistake, however, was to make herself the star in three consecutively unsuccessful movies, and ‘Venus-Film’ collapsed. Yet she still made the most of that boom period. Between 1949 and 1974 she had parts in twenty-two films, nearly half of them in 1950 and 1951.

With Babelsberg in the Soviet sector, the German movie industry was reborn in Munich, with American support. Olga Chekhova moved there herself in 1950. So did her granddaughter, Vera, who also wanted to become an actress. Olga realized at this time that she needed a new parallel career as her movie-making days came to an end. In 1952 she published her first volume of colourful and misleading memoirs under the shameless title

Ich verschweige nichts!

(

I Conceal Nothing!).

She also made her first move into the world of cosmetics, with the publication of a ‘beauty and fashion guide’ entitled

Frau ohne Alter (Ageless Woman).

Although full of Olga Chekhova’s rather trite philosophy of beauty, it adopted a surprisingly sexy approach for that repressive decade in Germany. Encouraged by the response, she decided to form her own cosmetics company.

‘Olga Tschechowa Kosmetik’ was set up in Munich in 1955, and ’expanded very rapidly‘. Considering that ’the millions which she had earned during her career were lost’ at the end of the war, and that ‘Venus-Film’ had so recently failed, it poses the question of where she managed to obtain financing. This is of interest because Soviet intelligence sources are absolutely convinced that Olga Tschechowa Kosmetik was set up almost entirely with money from Moscow. One even considers that it offered a very useful opportunity for making contact with the wives of NATO officers.

One must, however, treat such assertions with caution, since Russians still take great pride in the Soviet Union’s intelligence coups. This has encouraged exaggeration and myth-making. Stalin is even quoted as having said in 1943 that ‘the actress Olga Chekhova will be very useful in the post-war years’. On the basis of the evidence currently available, this seems an unlikely remark, yet perhaps there was more to her career than we know. SMERSh certainly treated her with an extraordinary degree of care and respect on her return to Germany in the summer of 1945. The KGB officers who passed Vova Knipper the batch of papers about his cousin referred to the case as ‘a complicated and somewhat unusual story’. There remain a considerable quantity of documents on the subject which have not seen, and probably never will see, the light of day.

Olga Chekhova, although not one of nature’s businesswomen considering her failures in the past, was nevertheless immensely disciplined and hard-working. Her extraordinary vitality, which had attracted men so much younger than herself, did not desert her even in her sixties. She still found time to appear in another six films while running Olga Tschechowa Kosmetik. She also encouraged her granddaughter, Vera, in her acting career.

Vera had caught the eye of the most famous member of the United States Army. On 2 March 1959, Private First Class Elvis Presley drove with his two companions, Lamar Fike and Red West, to Munich to visit Vera Chekhova at her grandmother’s house in Fresenius Strasse in Obermenzing. Presley had fallen for Vera, by then a beautiful nineteen-year-old, soon after he joined the US Seventh Army near Frankfurt am Main. During his visit to Munich, Vera was acting each evening in a play called

Der Verführer (The Seducer),

but the young couple saw a good deal of each other during the day. Presley even sat through a special screening of all her films, and he returned again in June.

In 1962, Olga Chekhova received the

Deutscher Filmpreis,

in her case a life-time achievement award ‘For many years of outstanding contribution to German Film’. More intriguing, after the row over her supposed Order of Lenin, was her award from the West German government in 1972. The President decorated her with the

Bundesverdienstkreuz,

the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic. She received it along with Konrad Lorenz.

In 1964, five years after Aunt Olya’s death, Olga Chekhova wrote to her companion, Sofya Baklanova. She announced that she intended to visit Moscow, accompanied by a small retinue including her masseur, her secretary and her doctor. She wanted a suite in the Hotel National and proposed to visit the graves of Uncle Anton and Aunt Olya in the Novodeviche cemetery. Among the forms she filled in, she claimed once again that she had acted at the Moscow Art Theatre under Stanislavsky’s direction. In the end, she never went. It was her last chance of seeing Lev.

Lev did, however, reply to a letter from Ada ten years later. He was still travelling, mostly in Siberia and Central Asia, and planning more musical projects. He was off to East Germany to produce a Symphony-Oratorium on Germany between 1933 and 1945. He was also working on an opera,

Count Cagliostro,

based on the novel by Aleksei Tolstoy, whom he had persuaded to return to the Soviet Union fifty years before. Lev continued to compose obsessively right up to his very last hours in July 1974. A final consolation for this morally tormented patriot was to receive the title of ‘People’s Artist of the USSR’ a few days before his death.

His sister clearly never suffered from political angst in any form. She continued to live in Obermenzing, where she refused to watch a single documentary on television about the war. She complained in a letter to her sister, Ada, that her cosmetics company was getting too large, with 140 employees. This authoritarian matriarch was clearly fed up with all the social aspects and personnel relationships involved. ‘A proletarian will always be a proletarian,’ she wrote. ‘The demands get bigger and bigger but the faculty of reason does not keep up!’

At the very end of her life, Olga Chekhova demonstrated both courage and an urge to follow family tradition. At the age of eighty-three, she was dying painfully from leukaemia, but never complained. On 9 March 1980, knowing that the end was near, she whispered her last request to her granddaughter, Vera.

When Anton Chekhov was on his deathbed in Badenweiler, he had told Aunt Olya that he would like a glass of champagne. He had drunk his champagne and then died. Olga Chekhova decided to follow his example. She was even able to direct Vera to the correct shelf in the wine cellar. When Vera returned, Olga Chekhova drank down the glass. Her last words were, ‘Life is beautiful.’

Although of German blood, Lutheran by baptism and German by nationality for over half a century, Olga Chekhova left instructions that she was to be buried according to Russian Orthodox rites.

Rumours about her mysterious life continued to grow. A German newspaper wrote that Himmler had wanted to arrest her in 1945, because by then he was convinced of her treachery. In Russia it was claimed that on Stalin’s personal order Olga Chekhova, with the help of the SS General Walter Schellenberg, went to the concentration camp where Stalin’s son, Jakov Djugashvili, was held, but she did not manage to save him. Some time later, the President of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, made a dramatic announcement about the Amber Room—that magnificent present from a Prussian King to a Russian Tsar, seized back by the Wehrmacht during the war and lost. Yeltsin claimed that he knew where this treasure was hidden in Thuringia and that the codename of this bunker was Olga. It would have been so suitable if it had proved true. Olga Chekhova was part of that ancient fascination between Russia and Germany, a dangerous borderland of shifting frontiers and loyalties.

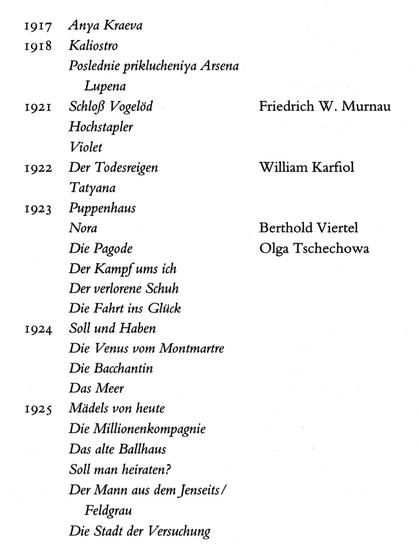

OLGA CHEKHOVA’S FILMS