The New Penguin History of the World (145 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

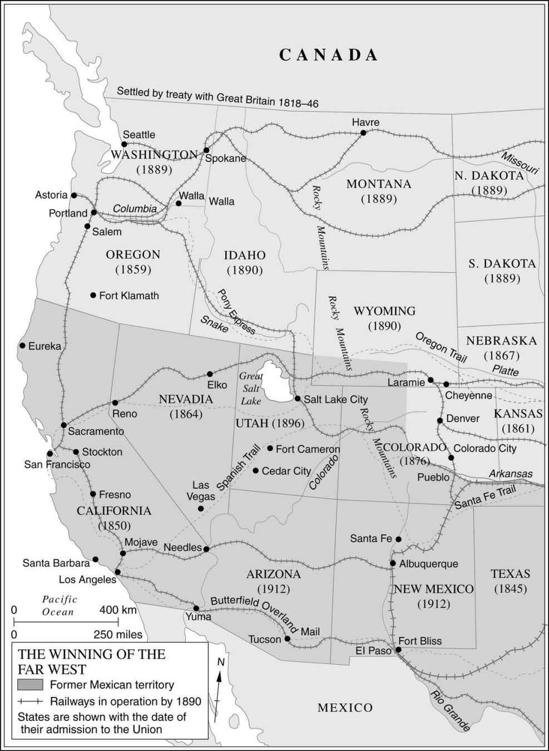

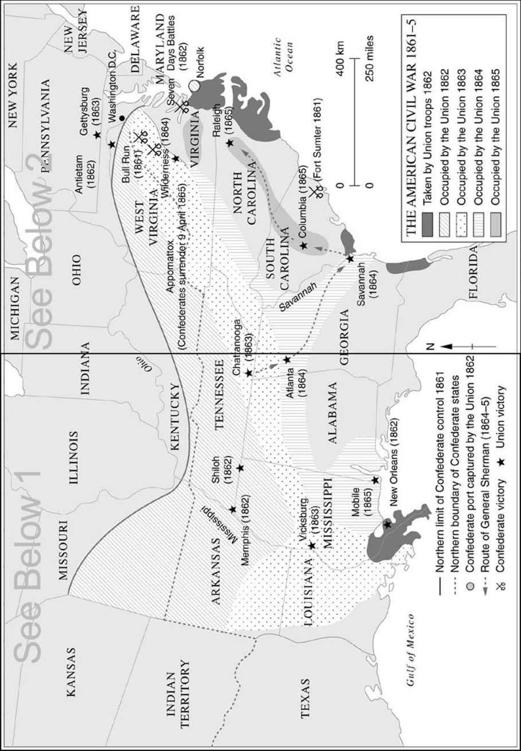

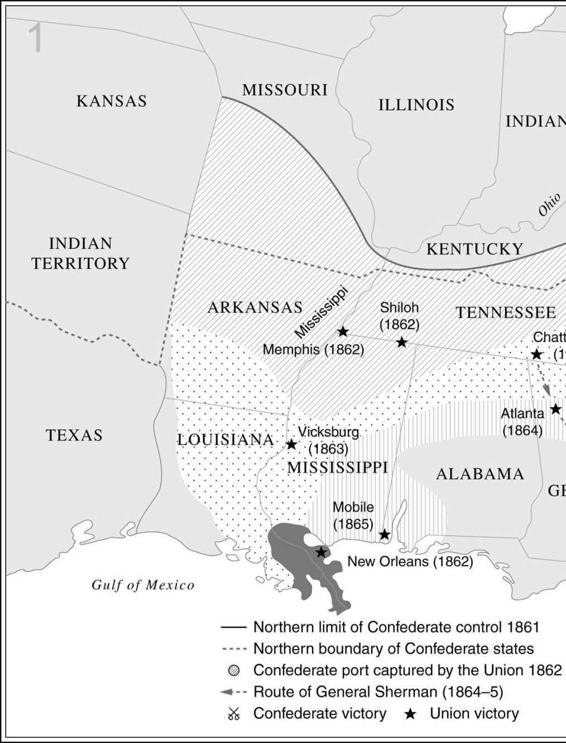

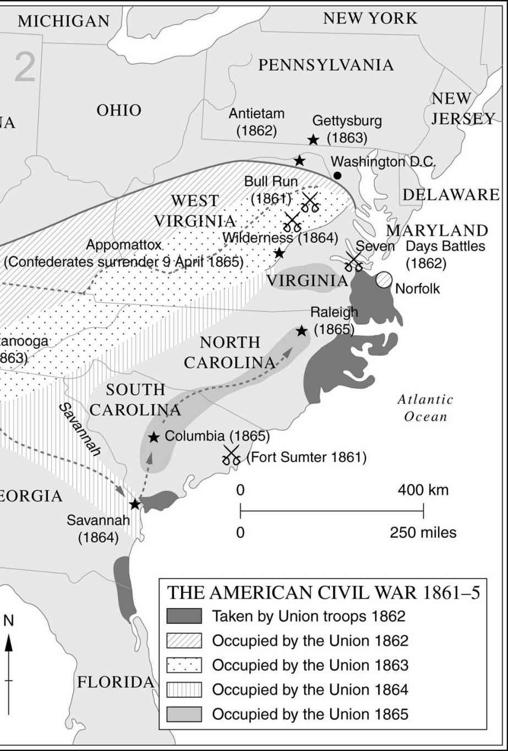

In the seventy years after the Peace of Paris the republic thus expanded, by conquest, purchase and settlement, to fill half a continent. Less than four million people in 1790 had become nearly twenty-four million by 1850. Most of these still lived east of the Mississippi, it was true, and the only cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were the three great Atlantic ports of Boston, New York and Philadelphia: none the less, the centre of gravity of the nation was moving westward. For a long time the political, commercial and cultural élites of the eastern seaboard would continue to dominate American society. But from the moment that the Ohio valley had been settled a western interest had been in existence; Washington’s farewell address had already recognized its importance. The West was an increasingly decisive contributor to the politics of the next seventy years, until there came to a head the greatest crisis in the history of the United States and one which settled her destiny as a world power.

Expansion, both territorial and economic, shaped American history as profoundly as the democratic bias of her political institutions. Its influence on those institutions, too, was very great and sometimes glaring; sometimes they were transformed. Slavery is the outstanding example. When Washington began his presidency there were a little under 700,000 black slaves within the territories of the Union. This was a large number, but the framers of the constitution paid no special attention to them, except in so far as questions of political balance between the different states were involved. In the end it had been decided that a slave should count as three-fifths of a free man in deciding how many representatives each state should have.

Within the next half-century three things revolutionized this state of affairs. The first was an enormous extension of slavery. It was driven by a rapid increase in the world’s consumption of cotton (above all in its consumption by the mills of England). This led to a doubling of the American crop in the 1820s and then its doubling again in the 1830s: by 1860, cotton provided two-thirds of the value of the total exports of the United States. This huge increase was obtained largely by cropping new land, and

new plantations meant more labour. By 1820 there were already a million and a half slaves, by 1860 about four million. In the southern states slavery had become the foundation of the economic system. Because of this, Southern society became even more distinctive; it had always been aware of the ways it differed from the more mercantile and urban northern states, but now its ‘peculiar institution’, as slavery was called, came to be regarded by Southerners as the essential core of a particular civilization. By 1860 many of them thought of themselves as a nation, with a way of life they idealized and believed to be threatened by tyrannous interference from the outside. The expression and symbol of this interference was, in their view, the growing hostility of Congress to slavery.

That slavery became a political issue was the second development changing its role in American life. It was part of a general evolution in American politics evident also in other ways. The early politics of the republic had reflected what were to be later called ‘sectional’ interests and the Farewell Address itself had drawn attention to them. Roughly speaking, they produced political parties reflecting, on the one hand, mercantile and business interests, which tended to look for strong federal government and protectionist legislation, and on the other, agrarian and consumer interests, which tended to assert the rights of individual states and to advocate cheap money policies. At that stage slavery was hardly a political question, although politicians sometimes spoke of it as an evil which must succumb (though no one quite knew how) with the passage of time. Such quiescence had gradually to change, partly as a result of the inherent tendencies of American institutions, partly because of social change. Judicial interpretation gave a strongly national and federal emphasis to the constitution. At the same time as congressional legislation was thus given new potential force, the law-makers were becoming more representative of American democracy; the presidency of Andrew Jackson has traditionally been seen as especially important in this. The growing democratization of politics reflected other changes; the United States was not to be troubled by an urban proletariat of those driven off the land, because in the West the possibility long existed of realizing the dream of independence; the social ideal of the independent smallholder could remain central to the American tradition. The opening up of the western hinterland by the Louisiana Purchase was as important in revolutionizing the distribution of wealth and population which shaped American politics as was the commercial and industrial growth of the North.

Above all, the opening of the West transformed the question of slavery. There was great scope for dispute about the terms on which new territories should be joined to the Union. As the organization first of the Louisiana

Purchase and then territory taken from Mexico had to be settled, the inflammatory question was bound to be raised: was slavery to be permitted in the new territories? A fierce anti-slavery movement had arisen in the North, which dragged the slavery issue to the forefront of American politics and kept it there until it overshadowed every other question. Its campaign for the ending of the slave trade and for the eventual emancipation of the slaves stemmed from much the same forces which had produced similar demands in other countries towards the end of the eighteenth century. But the American movement was importantly different, too. In the first place it was confronted with a

growth

of slavery at a time when it was disappearing elsewhere in the Europeanized world, so that the universal trend seemed to be at least checked, if not reversed, in the United States. Secondly, it involved a tangle of constitutional questions because of argument about the extent to which private property could be interfered with in individual states where local laws upheld it, or even in territories that were not yet states. Moreover, the anti-slavery politicians brought forward a question which lay at the heart of the constitution, and, indeed, of the political life of every European country, too: who was to have the last word? The people were sovereign, that was clear enough: but was the ‘people’ the majority of its representatives in Congress, or the populations of individual states acting through their state legislatures and asserting the indefeasibility of their rights even against Congress? Thus slavery came by mid-century to be entangled with almost every question raised by American politics.

These great issues were just contained so long as the balance of power between the Southern and Northern states remained roughly the same. Although the North had a slight preponderance of numbers, the crucial equality in the Senate (where each state had two senators, regardless of its population or size) was maintained. Down to 1819, new states were admitted to the Union on an alternating system, one slave, one free; there were then eleven of each. Then came the first crisis, over the admission of the state of Missouri. In the days before the Louisiana Purchase French and Spanish law permitted slavery there and its settlers expected this to continue. They were indignant, and so were representatives of the Southern states, when a Northern congressman proposed restrictions upon slavery in the new state’s constitution. There was great public stir and debate about sectional advantage; there was even talk of secession from the Union, so strongly did some Southerners feel. Yet the moral issue was muted. It was still possible to reach a political answer to a political question by the ‘Missouri Compromise’, which admitted Missouri as a slave state, but balanced her by admitting Maine at the same time, and prohibiting any further extension of slavery in United States territory north of a line of latitude 36° 30′. This confirmed the doctrine that Congress had the right to keep slavery out of new territories if it chose to exercise it, but there was no reason to believe that the question would again arise for a long time. Indeed, so it proved until a generation had passed. But already some had foreseen the future: Thomas Jefferson, a former president and the man who drafted the Declaration of Independence, wrote that he ‘considered it at once as the knell of the Union’, and another (future) president wrote in his diary that the Missouri question was ‘a mere preamble – a title-page to a great, tragic volume’.

Yet the tragedy did not come to a head for another forty years. In part this was because Americans had much else to think about – territorial expansion above all – and in part because no question arose of incorporating territories suitable for cotton-growing, and therefore requiring slave labour, until the 1840s. But there were soon forces at work to agitate public opinion and they would be effective when the public was ready to listen. It was in 1831 that a newspaper was established in Boston to advocate the unconditional emancipation of Negro slaves. This was the beginning of the ‘abolitionist’ campaign of increasingly embittered propaganda, electoral pressure upon politicians in the North, assistance to runaway slaves and opposition to their return to their owners after recapture, even when the law courts said they must be sent back. Against the background abolitionists provided, a struggle raged in the 1840s over the terms on which territory won from Mexico should be admitted. It ended in 1850

in a new Compromise, but one not to last long. From this time, politics were strained by increasing feelings of persecution and victimization among the Southern leaders and a growing arrogance on their part in the defence of their states’ way of life. National party allegiances were already affected by the slavery issue; the Democrats took their stand on the finality of the 1850 settlement.

The next decade brought descent into disaster. The need to organize Kansas blew up the truce which rested on the 1850 Compromise and brought about the first bloodshed as abolitionists strove to bully proslavery Kansas into accepting their views. There emerged a Republican party in protest against the proposal that the people living in the territory should decide whether Kansas should be slave or free: Kansas was north of the 36° 30′ line. The anger of abolitionists now mounted, too, whenever the law supported the slave-owner, as it did in a notable Supreme Court decision in 1857 (in the ‘Dred Scott’ case) which returned a slave to his master. In the South, on the other hand, such outcries were seen as incitements to disaffection among the blacks and a determination to use the electoral system against Southern liberties – a view which was, of course, justified, because the abolitionists, at least, were not men who would compromise, though they could not get the Republican party to support them. The Republican presidential candidate in the election of 1860 campaigned on a programme which in so far as it concerned slavery envisaged only the exclusion of slavery from all territories to be brought into the Union in the future.