The New Penguin History of the World (163 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The politicization of women, and political attacks on the legal and institutional structures which were felt by them to be oppressive, probably did less for women than did some other changes. Three of these were of slowly growing but, eventually, gigantic importance in undermining tradition. The first was the growth of the advanced capitalist economy. By 1914 this already meant great numbers of new jobs – as typists, secretaries, telephone operators, factory hands, department store assistants and teachers – for women in some countries. Almost none of these had existed a century earlier. They brought a huge practical shift of economic power to women: if they could earn their own living, they were at the beginning of a road

which would eventually transform family structures. Soon, too, the demands of warfare in the industrial societies would accelerate this advance as the need for labour opened an even wider range of occupations to them. Meanwhile, for growing numbers of girls even by 1900, a job in industry or commerce at once meant a chance of liberation from parental regulation and the trap of married drudgery. Most women did not by 1914 so benefit, but an accelerating process was at work, because such developments would stimulate other demands, for example, for education and professional training.

The second great transforming force was even further from showing its full potential to change women’s lives by 1914. This was contraception. It had already decisively affected demography. What lay ahead was a revolution in power and status as more women absorbed the idea that they might control the demands of child-bearing and rearing, which hitherto had throughout history dominated most women’s lives; beyond that lay an even deeper change, only beginning to be discerned in 1914, as women came to see that they could pursue sexual satisfaction without necessarily entering the obligation of lifelong marriage.

To the third great force moving women imperceptibly but irresistibly towards liberation from ancient ways and assumptions it is much harder to give an identifying single name, but if it has a governing principle, it is technology. It was a process made up of a vast number of innovations, some of them already slowly accumulating for decades before 1900 and all tending to cut into the iron timetables of domestic routine and drudgery, however marginally at first. The coming of piped water, or of gas for heating and lighting, are among the first examples; electricity’s cleanliness and flexibility was later to have even more obvious effects. Better shops were the front line of big changes in retail distribution, which not only gave a notion of luxury to people other than the rich, but also made it easier to meet household needs. Imported food, with its better processing and preserving, slowly changed habits of family catering once based – as they are still often based in India or Africa – on daily or twice daily visits to the market. The world of detergents and easily cleaned artificial fibres still lay in the future in 1900, but already soap and washing soda were far more easily and cheaply available than a century before, while the first domestic machines – gas cookers, vacuum cleaners, washing machines – began to make their appearance at least in the homes of the rich early in the twentieth century.

Historians who would recognize at once the importance of the introduction of the stirrup or the lathe in earlier times have none the less strangely neglected the cumulative force of such humble commodities and instruments

as these. Yet they implied a revolution for half the world. It is more understandable that their long-term implications interested fewer people at the beginning of the twentieth century than the antics of the ‘suffragettes’, as women who sought the vote were called in England. The immediate stimulus to their activity was the evident liberalization and democratization of political institutions in the case of men. This was the background which their campaign presupposed. Logically, there were grounds for pursuing democracy across the boundaries of sex even if this meant doubling the size of electorates.

But the formal and legal structure of politics was not the whole story of their tendency to show more and more of a ‘mass’ quality. The masses had to be organized. By 1900 there had appeared to meet this need the modern political party, with its simplifications of issues in order to present them as clear choices, its apparatus for the spread of political awareness, and its cultivation of special interests. From Europe and the United States it spread around the world. Old-fashioned politicians deplored the new model of party and by no means always did so insincerely, because it was another sign of the coming of mass society, the corruption of public debate and the need for traditional élites to adapt their politics to the ways of the man in the street.

The importance of public opinion had begun to be noticed in England early in the nineteenth century. It had been thought decisive in the struggles over the Corn Laws. By 1870, the French emperor felt he could not resist the popular clamour for a war which he feared and was to lose. Bismarck, the quintessential conservative statesman, felt soon afterwards that he must give way to public opinion and promote Germany’s colonial interests. The manipulation of public opinion, too, seemed to have become possible (or so, at least, many newspaper owners and statesmen believed). Growing literacy had two sides to it. It had been believed on the one hand that investment in mass education was necessary in order to civilize the masses for the proper use of the vote. What seemed to be the consequence of rising literacy, however, was that a market was created for a new cheap press, which often pandered to emotionalism and sensationalism, and for the sellers and devisers of advertising campaigns, another invention of the nineteenth century.

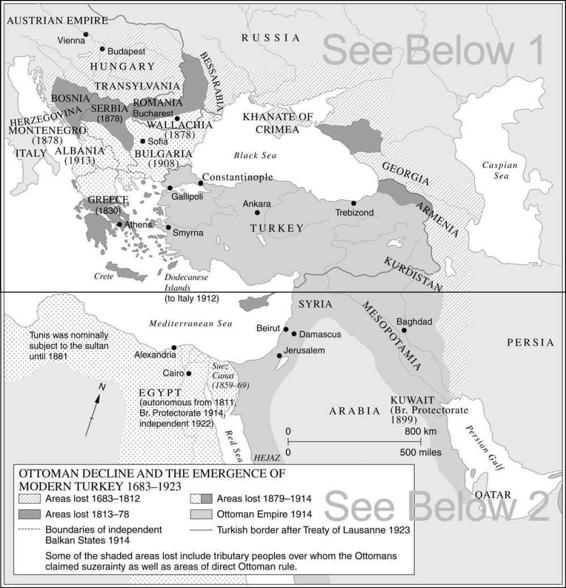

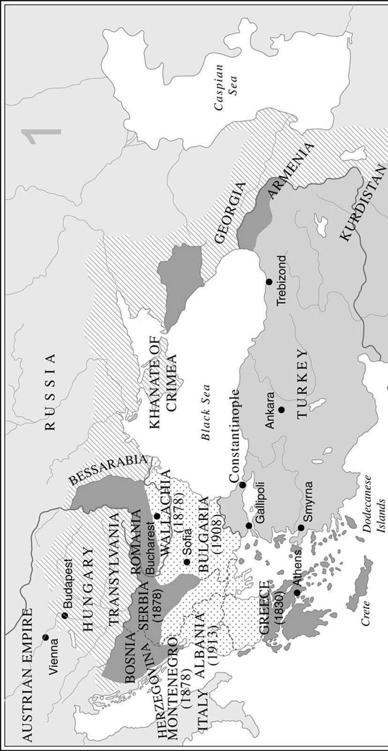

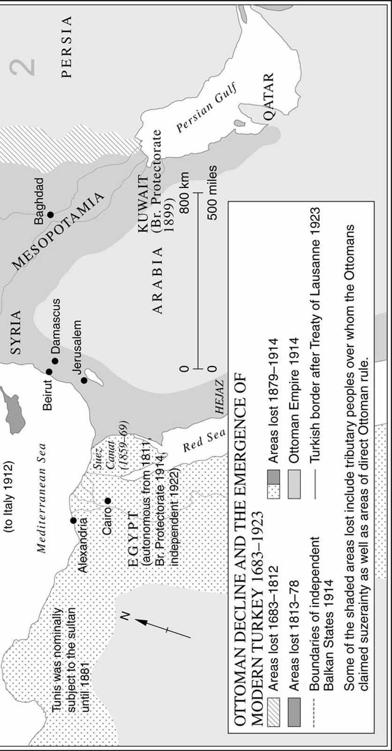

The political principle which undoubtedly still had the most mass appeal was nationalism. Moreover, it kept its revolutionary potential. This was clear in a number of places. In Turkish Europe, from the Crimean War onwards, the successes of nationalists in fighting Ottoman rule and creating new nations had hardly flagged. Serbia, Greece and Romania were solidly established by 1870. By the end of the century they had been joined by Bulgaria and Montenegro. In 1913, in the last wars of the Balkan states against Turkey before a European conflict swallowed the Turkish question, there appeared Albania, and by then an autonomous Crete already had a Greek governor. These nationalist movements had at several times dragged greater states into their affairs and always presented a potential danger to peace. This was not so true of those within the Russian empire, where Poles, Jews, Ukrainians and Lithuanians felt themselves oppressed by the Russians. War, though, seemed a more likely outcome of strains in the Austro-Hungarian empire, where nationalism presented a real revolutionary danger in the lands within the Hungarian half of the monarchy. Slav majorities there looked across the border to Serbia for help against Magyar oppressors. Elsewhere in the empire – in Bohemia and Slovakia, for example – feeling was less high, but nationalism was no less the dominant question. Great Britain faced no such dangers as these, but even she had a nationalist problem, in Ireland. Indeed, she had two. That of the Catholic

Irish was for most of the nineteenth century the more obvious. Important reforms and concessions had been granted, though they fell short of the autonomous state of ‘Home Rule’ to which the British Liberal Party was committed. By 1900, however, agricultural reform and better economic conditions had drawn much of the venom from this Irish question, although it was reinstated by the appearance of another Irish nationalism, that of the Protestant majority of the province of Ulster, which was excited to threaten revolution if the government in London gave Home Rule to the Roman Catholic Irish nationalists. This was much more than merely embarrassing. When the machinery of English democracy did finally deliver Home Rule legislation in 1914, some foreign observers were misled into thinking that British policy would be fatally inhibited from intervention in European affairs by revolution at home.

All those who supported such expressions of nationalism believed themselves with greater or less justification to do so on behalf of the oppressed. But the nationalism of the great powers was also a disruptive force. France and Germany were psychologically deeply sundered by the transfer of two provinces, Alsace and Lorraine, to Germany in 1871. French politicians whom it suited to do so, long and assiduously cultivated the theme of

revanche

. Nationalism in France gave especial bitterness to political quarrels because they seemed to raise questions of loyalty to great national institutions. Even the supposedly sober British from time to time grew excited about national symbols. There was a brief but deep enthusiasm for imperialism and always great sensitivity over the preservation of British naval supremacy. More and more this appeared to be threatened by Germany, a power whose obvious economic dynamism caused alarm by the danger it presented to British supremacy in world commerce. It did not matter that the two countries were one another’s best customers; what was more important was that they appeared to have interests opposed in many specific ways. Additional colour was given to this by the stridency of German nationalism under the reign of the third emperor, Wilhelm II. Conscious of Germany’s potential, he sought to give it not only real but symbolic expression. One effect was his enthusiasm for building a great navy; this especially annoyed the British who could not see that it could be intended for use against anyone but them. But there was a generally growing impression in Europe, far from unjustified, that the Germans were prone to throw their weight about unreasonably in international affairs. National stereotypes cannot be summarized in a phrase, but because they helped to impose terrible simplifications upon public reactions they are part of the story of the disruptive power of nationalist feeling at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Those who felt confident could point to the diminution of international violence in the nineteenth century; there had been no war between European great powers since 1876 (when Russia and Turkey had come to blows) and, unhappily, European soldiers and statesmen failed to understand the portents of the American civil war, the first in which one commander could control over a million men, thanks to railway and telegraph, and the first to show the power of modern mass-produced weapons to inflict huge casualties. While such facts were overlooked, the summoning of congresses in 1899 and 1907 to halt competition in armaments could be viewed optimistically, though they failed in their aim. Certainly acceptance of the practice of international arbitration had grown and some restrictions on the earlier brutality of warfare were visible. A significant phrase was used by the German emperor when he sent off his contingent to the international force fielded against the Chinese Boxers. Stirred to anger by reports of atrocities against Europeans by Chinese, Wilhelm urged his soldiers to behave ‘like Huns’. The phrase stuck in people’s memories. Though thought to be excessive even at the time its real interest lies in the fact that he should have believed such an instruction was needed. Nobody would have had to tell a seventeenth-century army to behave like Huns, because it was in large measure then taken for granted that they would. By 1900, European troops were not expected to behave in this way and had therefore to be told to do so. So far had the humanizing of war come. ‘Civilized warfare’ was a nineteenth-century concept and far from a contradiction in terms. In 1899 it had been agreed to forbid, albeit for a limited period, the use of poison gas, dum-dum bullets and even the dropping of bombs from the air.