The New Penguin History of the World (184 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The war of 1939 was to release change in the Middle East as elsewhere, though this was not at first clear. After Italy’s entry to the war, the Canal Zone became one of the most vital areas of British strategy and Egypt suddenly found herself with a battlefront for a western border. She remained neutral almost to the end, but was in effect a British base and little else. The war also made it essential to assure the supply of oil from the Gulf and especially from Iraq. This led to intervention when Iraq threatened to move in a pro-German direction after another nationalist coup in 1941. A British and Free French invasion of Syria to keep it out of German hands led in 1941 to an independent Syria. Soon afterwards the Lebanon proclaimed its independence. The French tried to re-establish their authority at the end of the war, but unsuccessfully, and during 1946 these two countries saw the last foreign garrisons leave. The French also had difficulties further west, where fighting broke out in Algeria in 1945. Nationalists there were at that moment asking only for autonomy in federation with France and the French went some way in this direction in 1947, but this was far from the end of the story.

Where British influence was paramount, anti-British sentiment was still a good rallying-cry. In both Egypt and Iraq there was much hostility to British occupation forces in the post-war years. In 1946 the British announced that they were prepared to withdraw from Egypt, but negotiations on the basis of a new treaty broke down so badly that Egypt referred the matter (unsuccessfully) to the United Nations. By this time the whole question of the future of the Arab lands had been diverted by the Jewish decision to establish a national state in Palestine by force.

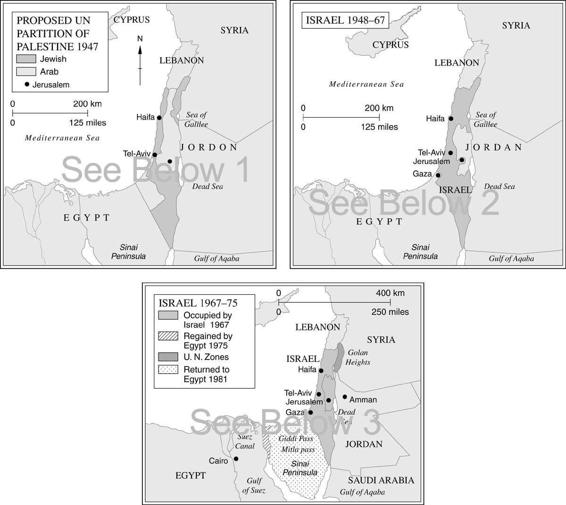

The Palestine question has been with us ever since. Its catalyst had been the Nazi revolution in Germany. At the time of the Balfour Declaration 600,000 Arabs had lived in Palestine beside 80,000 Jews – a number already felt by Arabs to be threateningly large. In some years after this, though, Jewish emigration actually exceeded immigration and there was ground for hope that the problem of reconciling the promise of a ‘national home’ for Jews with respect for ‘the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’ (as the Balfour Declaration had put it) might be resolved. Hitler changed this.

From the beginning of the Nazi persecution the numbers of those who wished to come to Palestine rose. As the extermination policies began to unroll in the war years, they made nonsense of British attempts to restrict immigration, which was the side of British policy unacceptable to the Jews; the other side – the partitioning of Palestine – was rejected by the Arabs. The issue was dramatized as soon as the war was over by a World Zionist Congress demand that a million Jews should be admitted to Palestine at once. Other new factors now began to operate. The British, in 1945, had looked benevolently on the formation of an ‘Arab League’ of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the Yemen and Transjordan. There had always been in British policy a strand of illusion – that pan-Arabism might prove the way in which the Middle East could be persuaded to settle down after post-Ottoman confusion, and that the coordination of the policies of Arab states would open the way to the solution of its problems. In fact the Arab League was soon preoccupied with Palestine to the virtual exclusion of anything else.

The other novelty was the Cold War. In the immediate post-war era, Stalin seems to have taken still the old communist view that Great Britain was the main imperialist prop of the international capitalist system. Attacks on its position and influence therefore followed, and in the Middle East this, of course, coincided with traditional Russian interests, though the Soviet government had shown little interest in the area between 1919 and 1939. Pressure was brought to bear on Turkey at the Straits, and ostentatious Soviet support was given to Zionism, the most disruptive element in the situation. It did not need extraordinary political insight to recognize the implications of a resumption of Russian interest in the area of the Ottoman legacy. Yet at the same moment American policy turned anti-British or, rather, pro-Zionist. This could hardly have been avoided. In 1946 mid-term congressional elections were held and Jewish votes were important. Since the Roosevelt revolution in domestic politics, a Democratic president could hardly envisage an anti-Zionist position.

Thus beset, the British sought to disentangle themselves from the Holy Land. From 1945 they faced both Jewish and Arab terrorism and guerrilla warfare in Palestine. Unhappy Arab, Jewish and British policemen struggled to hold the ring while the British government still strove to find a way acceptable to both sides of bringing the mandate to an end. American help was sought, but to no avail; Truman wanted a pro-Zionist solution. In the end the British took the matter to the United Nations. It recommended partition, but this was still a non-starter for the Arabs. Fighting between the two communities grew fiercer and the British decided to withdraw without more ado. On the day that they did so, 14 May 1948, the state of Israel was proclaimed. It was immediately recognized by the United

States (sixteen minutes after the foundation act) and the USSR; they were to agree about little else in the Middle East for the next quarter-century.

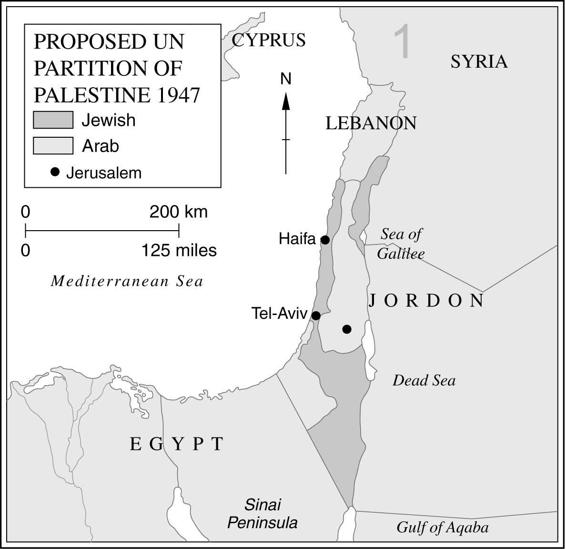

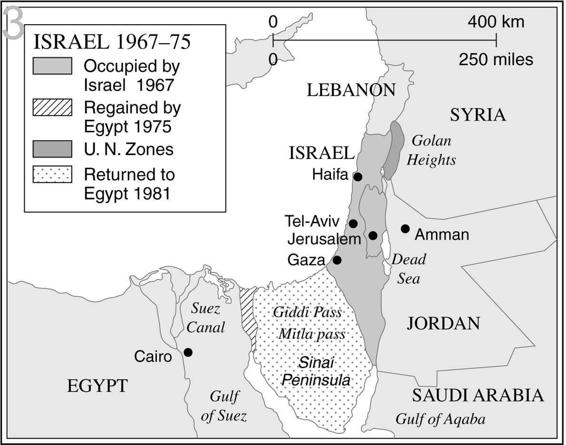

Israel was attacked almost at once by Egypt, whose armies invaded a part of Palestine which the United Nations proposal had awarded to Jews. Jordanian and Iraqi forces supported Palestinian Arabs in the territory proposed for them. But Israel fought off her enemies, and a truce, supervised by the United Nations, followed (during which a Zionist terrorist murdered the United Nations mediator). In 1949 the Israeli government moved to Jerusalem, a Jewish national capital again for the first time since the days of imperial Rome. Half of the city was still occupied by Jordanian forces, but this was almost the least of the problems left to the future. With American and Russian diplomatic support and American private money, Jewish energy and initiative had successfully established a new national state where no basis for one had existed twenty-five years before. Yet the cost was long to go on being paid. The disappointment and humiliation of the Arab states assured their continuing hostility to it and therefore opportunities for great power intervention in the future. Moreover, the action of Zionist extremists and Israeli forces in 1948–9 led to an exodus of Arab refugees. Soon there were 750,000 of them in camps in Egypt and Jordan, a social and economic problem, a burden on the world’s conscience, and a potential military and diplomatic weapon for Arab nationalists. It would hardly be surprising were it true (as some students believe) that the first president of Israel quickly encouraged his country’s scientists to work on a nuclear energy programme.

Thus, many currents flowed together in a curious and ironical way to swirl in confusion in an area which had always been a focus of world history. Victims for centuries, the Jews were in their turn now seen by Arabs as persecutors. The problems with which the peoples of the area had to grapple were poisoned by forces flowing from the dissolution of centuries of Ottoman power, from the rivalries of successor imperialisms (and in particular from the rise of two new world powers, which dwarfed these in their turn), from the interplay of nineteenth-century European nationalism and ancient religion, and from the first effects of a new dependence of developed nations on oil. There are few moments in the twentieth century so soaked in history as the establishment of Israel. It is a good point at which to pause before turning to the story of the rest of the twentieth century.

BOOK EIGHT

The Latest Age

Even as the twentieth century of the Christian era began to close, it was already easy enough to agree that great and startling changes had come about since, say, 1945. Today, that is even more apparent. But the problems which arise as we try to pin them down as part of the world’s history do not go away. They may even become more difficult to solve. The mere narrative of events seems to thicken up suddenly, unaccountably, and of its own accord. It is harder than ever, under the strong impression of recent events, to get our perspective right in treating the last fifty or so years of history in relation to the preceding six thousand or so.

Part of the trouble lies in our reasonable expectations. When we read about times through which we have lived, we expect to come across events we recall, or recall hearing about at an impressionable age, and there is then a sense of disappointment if they do not turn up in the story. But all history is a selection; it is, in the strictest sense, what any one age finds remarkable in an earlier period, and expectation, legitimate or illegitimate, is only a part of it. Nor is it the only source of challenge in the history of recent times. The pace of change poses another difficulty. It was only a few centuries ago that the notion of human cultural evolution began to get some grip on writers of history. It is really only very recently, moreover, that historians have begun to take it for granted that generations will differ culturally, that the societies they live in are always changing in very deep and determining ways, and that basic attitudes change with them. Yet any adult alive today has almost certainly lived through examples of radical adaptations which are now taken for granted, absorbed into our consciousness and often go unremarked, though they have been far more profound and far more strikingly rapid than any experienced by our predecessors. The growth of population is the exemplary case; no earlier generation has lived through anything like such a rapid increase in human numbers. Yet few human beings have been conscious of it.

It is not just as a succession of events that history has speeded up. The rapidity of the changes it has brought has often had wider and deeper

implications, and more influence than in the past, just because of the speed with which the changes came about. To take one example, for all the dissatisfactions still felt by many over the extent of advance, the opportunities and freedoms available to women in western society have grown at a quite different rate and by an order of magnitude dramatically greater than in earlier centuries. As yet, they have not begun to exhaust (or in some places even to exercise) their full effect. The same could be said of many more narrowly technological and material changes, some of which are far from exercising their full potential effects.