The New Penguin History of the World (54 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Such facts had already led in the second century

AD

to intense fighting over Armenia, its details often obscure. Severus eventually penetrated Mesopotamia but had to withdraw; the Mesopotamian valleys were too far away. The Romans were trying to do too much and faced the classic problem of over-extended imperialism. But their opponents were tiring and at low ebb, too. Parthian written records are fragmentary, but the tale of exhaustion and growing incompetence emerges from a coinage declining into unintelligibility and blurred derivations from earlier Hellenized designs.

In the third century Parthia disappeared, but the threat to Rome from

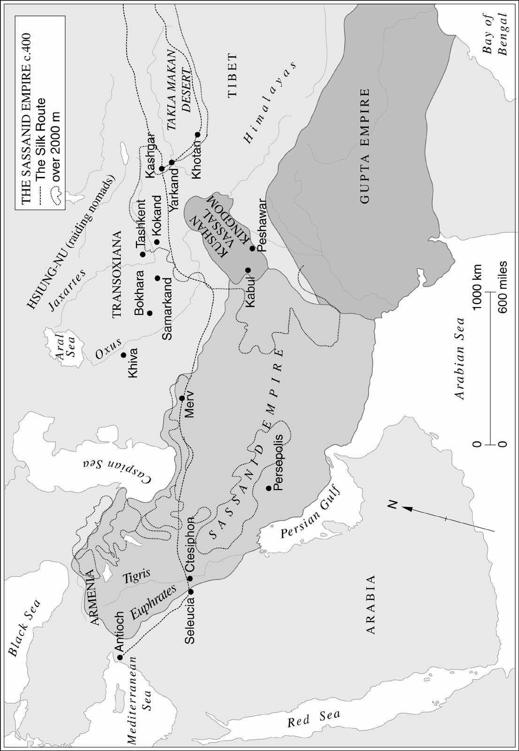

the East did not. A turning-point was reached in the history of the old area of Persian civilization. In about 225 a king called Ardashir (later known in the West as Artaxerxes) killed the last king of Parthia and was crowned in Ctesiphon. He was to re-create the Achaemenid empire of Persia under a new dynasty, the Sassanids; it would be Rome’s greatest antagonist for more than four hundred years. There was much continuity here; the Sassanid empire was Zoroastrian, as Parthia had been, and evoked the Achaemenid tradition as Parthia had done.

Within a few years the Persians had invaded Syria and opened three centuries of struggle with the empire. In the third century there was not a decade without war. The Persians conquered Armenia and took one emperor (Valerian) prisoner. Then they were driven from Armenia and Mesopotamia in 297. This gave the Romans a frontier on the Tigris, but it was not one they could keep for ever. Neither could the Persians keep their conquests. The outcome was a long-drawn-out and ding-dong contest. A sort of equilibrium grew up in the fourth and fifth centuries and only in the sixth did it begin to break down. Meanwhile, commercial ties appeared. Though trade at the frontier was officially limited to three designated towns, important colonies of Persian merchants came to live in the great cities of the empire. Persia, moreover, lay across trade routes to India and China which were as vital to Roman exporters as to those who wanted oriental silk, cotton and spices. Yet these ties did not offset other forces. When not at war, the two empires tended to coexist with cold and cautious hostility; their relations were complicated by communities and peoples settled on both sides of the frontier, and there was always the danger of the strategic balance being upset by a change in one of the buffer kingdoms – Armenia, for instance. The final round of open struggle was put off, but came at last in the sixth century.

This is to jump too far ahead for the present; by then huge changes had taken place in the Roman empire which have still to be explained. The conscious dynamism of the Sassanid monarchy was only one of the pressures encouraging them. Another came from the barbarians along the Danube and Rhine frontiers. The origins of the folk-movements which propelled them forward in the third century and thereafter must be sought in a long development and are less important than the outcome. These peoples grew more insistent, acted in larger groupings and had, in the end, to be allowed to settle inside Roman territory. Here they were first engaged as soldiers to protect the empire against other barbarians and then, gradually, began to take a hand in running the empire themselves.

In 200 this still lay in the future; all that was clear then was that new pressures were building up. The most important barbarian peoples involved were the Franks and Alamanni on the Rhine and the Goths on the lower Danube. From about 230 the empire was struggling to hold them off but the cost of fighting on two fronts was heavy; his Persian entanglements soon led one emperor to make concessions to the Alamanni. When his immediate successors added their own quarrels to their Persian burdens the Goths took advantage of a promising situation and invaded Moesia, the province immediately south of the Danube, killing an emperor there

en passant

in 251. Five years later, the Franks crossed the Rhine. The Alamanni followed and got as far as Milan. Gothic armies invaded Greece and raided Asia and the Aegean from the sea. Within a few years the European dams seemed to give way everywhere at once.

The scale of these incursions is not easy to establish. Perhaps the barbarians could never field an army of more than twenty or thirty thousand. But this was too much at any one place for the imperial army. Its backbone was provided by recruits from the Illyrian provinces; appropriately, it was a succession of emperors of Illyrian stock who turned the tide. Much of what they did was simple good soldiering and intelligent extemporization. They recognized priorities; the main dangers lay in Europe and had to be dealt with first. Alliance with Palmyra helped to buy time against Persia. Losses were cut; trans-Danubian Dacia was abandoned in 270. The army was reorganized to provide effective mobile reserves in each of the main danger areas. This was all the work of Aurelian, whom the Senate significantly called ‘Restorer of the Roman empire’. But the cost was heavy. A

more fundamental reconstruction was implicit if the work of the Illyrian emperors was to survive and this was the aim of Diocletian. A soldier of proven bravery, he sought to restore the Augustan tradition but revolutionized the empire instead.

Diocletian had an administrator’s genius rather than a soldier’s. Without being especially imaginative, he had an excellent grasp of organization and principles, a love of order and great skill in picking and trusting men to whom he could delegate. He was also energetic. Diocletian’s capital was wherever the imperial retinue found itself; it moved about the empire, passing a year here, a couple of months there, and sometimes only a day or two in the same place. The heart of the reforms which emerged from this court was a division of the empire intended to deliver it both from the dangers of internal quarrels between pretenders in remote provinces and from the over-extension of its administrative and military resources. In 285 Diocletian appointed a co-emperor, Maximian, with responsibility for the empire west of a line running from the Danube to Dalmatia. The two

augusti

were subsequently each given a

caesar

as co-adjutor; these were to be both their assistants and successors, thus making possible an orderly transfer of power. In fact, the machine of succession only once operated as Diocletian intended, at his own abdication and that of his colleague, but the practical separation of administration in two imperial structures was not reversed. After this time all emperors had to accept a large measure of division even when there was nominally still only one of them.

There also now emerged explicitly a new conception of the imperial office. No longer was the title

princeps

employed; the emperors were the creation of the army, not the Senate, and were deferred to in terms recalling the semi-divine kingship of oriental courts. Practically, they acted through pyramidal bureaucracies. ‘Dioceses’, responsible directly to the emperors through their ‘vicars’, grouped provinces much smaller and about twice as numerous as the old ones had been. The senatorial monopoly of governmental power had long since gone; senatorial rank now meant in effect merely a social distinction (membership of the wealthy landowning class) or occupation of one of the important bureaucratic posts. Equestrian rank disappeared.

The military establishment of the Tetrachy, as it was called, was much larger (and therefore more expensive) than that laid down originally by Augustus. The theoretical mobility of the legions, deeply dug into long occupied garrisons, was abandoned. The army of the frontiers was now broken up into units, some of which remained permanently in the same place while others provided new mobile forces smaller than the old legions. Conscription was reintroduced. Something like a half-million men were

under arms. Their direction was wholly separated from the civilian government of the provinces with which it had once been fused.

The results of this system do not seem to have been exactly what Diocletian envisaged. They included a considerable measure of military recovery and stabilization, but its cost was enormous. An army, whose size doubled in a century, had to be paid for by a population which had probably already begun to shrink. Heavy taxation not only compromised the loyalty of the empire’s subjects and encouraged corruption; it also required a close control of social arrangements so that the tax base should not be eroded. There was great administrative pressure against social mobility; the peasant, for example, was obliged to stay where he was recorded at the census. Another celebrated (though so far as can be seen totally unsuccessful) example was the attempt to regulate wages and prices throughout the empire by a freeze. Such efforts, like those to raise more taxation, meant a bigger civil service, and as the number of administrators increased so, of course, did the overheads of government.

In the end Diocletian probably achieved most by opening the way to a new view of the imperial office itself. The religious aura which it acquired was a response to a real problem. Somehow, under the strain of continued usurpation and failure the empire had ceased to be unquestioningly accepted. This was not merely because of dislike of higher taxation or fear of its growing numbers of secret police. Its ideological basis had been eroded and it could not focus men’s loyalties. A crisis of civilization was going on as well as a crisis of government. The spiritual matrix of the classical world was breaking up; neither state nor civilization was any longer to be taken for granted and they needed a new ethos before they could be.

An emphasis on the unique status of the emperor and his sacral role was one early response to this need. Consciously, Diocletian acted as a saviour, a Jupiter-like figure holding back chaos. Something in this recalled affinities with those thinkers of the late classical world who saw life as a perpetual struggle of good and evil. Yet this was a vision not Greek or Roman at all, but oriental. The acceptance of a new vision of the emperor’s relation to the gods, and therefore of a new conception of the official cult, did not bode well for the traditional practical tolerance of the Greek world. Decisions about worship might now decide the fate of the empire.

These possibilities shaped the history of the Christian Churches for both good and ill. In the end Christianity was to be the legatee of Rome. Many religious sects have risen from the position of persecuted minorities to become establishments in their own right. What sets the Christian Church apart is that this took place within the uniquely comprehensive structure

of the late Roman empire, so that it both attached itself to and strengthened the lifeline of classical civilization, with enormous consequences not only for itself but for Europe and ultimately the world.

At the beginning of the third century missionaries had already carried the faith to the non-Jewish peoples of Asia Minor and North Africa. Particularly in North Africa, Christianity had its first mass successes in the towns; it long remained a predominantly urban phenomenon. But it was still a matter of minorities. Throughout the empire, the old gods and the local deities held the peasants’ allegiance. By the year 300 Christians may have made up only about a tenth of the population of the empire. But there had already been striking signs of official favour and even concession. One emperor had been nominally a Christian and another had included Jesus Christ among the gods honoured privately in his household. Such contacts with the court illustrate an interplay of Jewish and classical culture which is an important part of the story of the process by which Christianity took root in the empire. Perhaps Paul of Tarsus, the Jew who could talk to Athenians in terms they understood, had launched this. Later, early in the second century, Justin Martyr, a Palestinian Greek, had striven to show that Christianity had a debt to Greek philosophy. This had a political point; cultural identification with the classical tradition helped to rebut the charge of disloyalty to the empire. If a Christian could stand in the ideological heritage of the Hellenistic world he could also be a good citizen, and Justin’s rational Christianity (even though he was martyred for it in about 165) envisaged a revelation of the Divine Reason in which all the great philosophers and prophets had partaken, Plato among them, but which was only complete in Christ. Others were to follow similar lines, notably the learned Clement of Alexandria, who strove to integrate pagan scholarship with Christianity, and Origen (though his exact teaching is still debated because of the disappearance of many of his writings). A North African Christian, Tertullian, had contemptuously asked what the Academy had to do with the Church; he was answered by the Fathers who deliberately employed the conceptual armoury of Greek philosophy to provide a statement of the faith which anchored Christianity to rationality as Paul had not done.

When coupled to its promise of a salvation after death and the fact that the Christian life could be lived in a purposeful and optimistic way, such developments might lead us to suppose that Christians were by the third century confident about the future. In fact, favourable portents were much less striking than the persecutions so prominent in the history of the early Church. There were two great outbreaks. That of the middle of the century expressed the spiritual crisis of the establishment. It was not only economic

strain and military defeat that were troubling the empire, but a dialectic inherent in Roman success itself: the cosmopolitanism which had been so much the mark of the empire was, inevitably, a solvent of the

romanitas

, which was less and less a reality and more and more a slogan. The emperor Decius seems to have been convinced that the old recipe of a return to traditional Roman virtue and values could still work; it implied the revival of service to the gods whose benevolence would then be once more deployed in favour of the empire. The Christians, like others, must sacrifice to the Roman tradition, said Decius, and many did, to judge by the certificates issued to save them from persecution; some did not, and died. A few years later, Valerian renewed persecution on the same grounds, though his proconsuls addressed themselves rather to the directing personnel and the property of the Church – its buildings and books – than to the mass of believers. Thereafter, persecution ebbed, and the Church resumed its shadowy, tolerated existence just below the horizon of official attention.