The Norm Chronicles (30 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

When radiation is used to help diagnose or treat medical problems, most people are again like Prudence – relatively untroubled. The history of its medical use has been sublimely blasé. From the first use of X-rays in the 1890s, the magical ability to see inside the body belittled the harm they could cause. Never mind that Edison’s assistant Clarence Dally and numerous radiologists died early. After radium was discovered by the Curies, radioactivity was thought of as a source of health and healing. In 1909 Dr E. Skillman Bailey reported to the Southern Homeopathic Medical Association in New Orleans his investigations of Radithor, which enabled him to ‘photograph objects through 6 inches of wood’. He used it for medical treatments, although he was no doctor and was said to exhibit ‘visible signs of being unstrung’. He even passed a sample around the audience. Nevertheless Radithor – ‘Radioactive water, a cure for the living dead’ – was a success and sold hundreds of thousands of bottles until forced to close in 1932 owing to bad publicity following the death of the steel millionaire and playboy Eben Byers from radiation poisoning. Byers consumed over 1,400 bottles. The

Wall Street Journal

headline was: ‘The radium water worked fine until his jaw came off.’

There were no radiation safety standards until the 1920s. They’ve grown increasingly stringent ever since: X-ray ‘Pedascopes’ for fitting children’s shoes were banned, as was the ‘treatment’ with X-rays of children with ringworm, and mental patients with radium. Nevertheless, X-rays and CT scans are still carried out in huge numbers.

People also seem rather unconcerned about natural background radiation arising from sources such as cosmic rays and radon, a radioactive gas from uranium in rocks such as granite. Radon, which can collect in ill-ventilated rooms, is estimated to cause 1,100 preventable lung

cancer deaths in the UK each year. But these exposures do not arouse the strong feelings associated with nuclear power.

John Adams cites mobile phones as another example of apparent inconsistency that picks up on one aspect of dread: choice.

The risk associated with the handsets is either non-existent or very small. The risk associated with the base stations, measured by radiation dose, unless one is up the mast with an ear to the transmitter, is orders of magnitude less. Yet all around the world billions of people are queuing up to take the voluntary handset risk, and almost all the opposition is focused on the base stations, which are seen by objectors as impositions.

1

Since the phone is useless without the transmitter, that appears odd. Except that you can’t choose where the transmitter goes.

In a now classic paper from 1989 on the differences between lay and expert opinion about risk, Paul Slovic said that ‘dread’ expressed a subtlety that the experts sometimes overlooked. ‘There is wisdom as well as error in public attitudes and perceptions. Lay people sometimes lack certain information about hazards. However, their basic conceptualization of risk is much richer than many of the experts and reflects legitimate concerns that are typically omitted from expert risk analysis.’

2

While acknowledging these concerns, it is still valuable to get a handle on the magnitude of the hazard. So what are the exposures? The units are confusing. It’s easiest to focus on the Sievert, which is a measure of the biological effect of being exposed to radiation. One Sievert – or 1Sv – can cause radiation sickness, which might mean hair loss, bloody vomit and stools, weakness, dizziness, headache, fever, skin redness, itching or blistering, infections, poor wound healing and low blood pressure. Not nice.

One Sievert can be broken down into a thousand milli-Sieverts (1 milli-Sievert – or 1mSv – is the US Environmental Protection Agency limit for annual exposure of a member of the public) and a million micro-Sieverts. A tenth of 1 micro-Sievert is about the dose from eating

a large banana – Prudence’s evening snack – or going through a whole-body scanner at an airport.

3

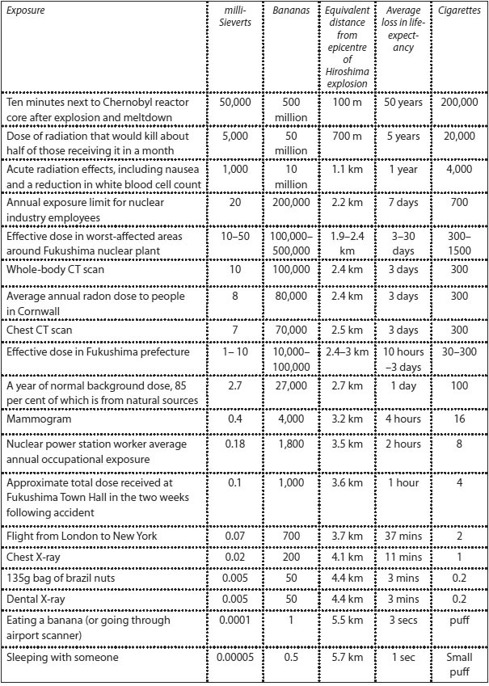

The radiation dose chart,

Figure 22

(overleaf), is a fun but imperfect way of comparing radiation from the mass of different sources by converting Sieverts into a banana equivalent dose, or BED (imperfect mainly because the radiation in bananas comes from potassium, and the body can regulate this). The virtue of this whimsical unit is that it shows the enormous range of exposures on one scale. Five hundred million bananas – depending, of course, on the size of the banana – is about 50 Sieverts, the equivalent of ten minutes next to Chernobyl power station during meltdown. This helps make the point that many hazards are not a hazard at all if the dose is low enough. After all, who’ s worried about one banana?

This chart is a very minor publishing scandal, by the way, and may get us into trouble. Most advice on risk communication is to avoid mixing voluntary with involuntary risks. But if one of the complaints about the emotions in dread is that they make people immune to data, then maybe one way to overcome this is to make the data emotionally shocking. Bananas, CT scans and Chernobyl? You bet. Just like horse-riding compared with Ecstasy, it is outrageous, but fascinating, and in our view genuinely helps to put risks in proportion. If perceptions are what often determine risk, then surprising perspectives have a part to play.

Most of our knowledge about the harmful effects of radiation comes from detailed studies of the victims of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Around 200,000 people died immediately or within a few months, but 87,000 survivors have been followed up for their whole lives. By 1992 over 40,000 had died, although it’s estimated that only 690 of those deaths were due to the radiation. Bomb victims had been exposed to radiation roughly according to the dosage shown in the table: the dose declines rapidly, halving every 200 metres, and so, according to a US National Academy of Sciences report, someone around 1½ miles (2.5 km) from the epicentre received around the same dose as from a modern CT scan.

5

What would Prudence say?

The number of victims of the Chernobyl accident is more controversial: a United Nations report says that acute radiation sickness has killed

28 people, and that 6,000 children developed thyroid cancer through drinking contaminated milk, an easily preventable event.

6

Of these, 15 had died by 2005, but the report adds that ‘to date, there has been no persuasive evidence of any other health effect in the general population that can be attributed to radiation exposure’.

Figure 22:

Approximate radiation exposure from different sources, converted into: banana-equivalents, equivalent distance from epicentre of Hiroshima explosion, average loss in life-expectancy and cigarette-equivalents

Note: 1,000 micro-Sieverts (10,000 bananas) = 1 milli-Sievert; 1,000 milli-Sieverts = 1 Sievert.

Others claim the true figures are far higher. It all depends on what you believe about the effects of low levels of radiation. When experts say there is no evidence of extra harm, this is hardly surprising, as even if there had been an increase in cancers downwind of Chernobyl, they would be impossible to detect given the vast numbers that occur anyway. So any estimate would have to be based on a theoretical model of harm.

Using these models, it is estimated that on average roughly one year of life is lost per Sievert exposure.

7

When setting regulations, these effects are extrapolated down to much lower doses for which there is no direct evidence of harm; this is known as the Linear No Threshold (LNT) hypothesis. If we assume LNT, then 1 mSv is 1/1000th of a year lost, which is 9 hours of life or 18 MicroLives. So, as a mammogram is 0.4 mSv, this is equivalent to 8 MicroLives, or around 16 cigarettes. Both average loss in life-expectancy and cigarette equivalent are shown in the table.

The LNT hypothesis is controversial: the people working out the effects of Chernobyl did not use it, and some claim that low doses do not have a proportional effect since the body has time to heal itself. But if we accept the LNT idea, then we can get some remarkable conclusions about the ‘nice’ use of radiation to help sick people.

For example, a CT scan of 10mSv comes in at 180 MicroLives, or around 360 cigarettes. This may not seem too large for an individual getting a diagnosis, but over large numbers of people it adds up: the US National Cancer Institute estimate that the 75 million CT scans in the US in 2007 alone will eventually cause 29,000 cancers.

8

None of this was discussed when the apocalyptic visions of destruction brought about by the Japanese earthquake and subsequent tsunami in March 2011 were largely replaced in the media by reports of the struggle to control radiation from the stricken Fukushima nuclear plant. This

ticked all the boxes for dread: invisible, uncontrollable, associated with cancer and birth defects. Add an untrusted power company into the mix and the psychological consequences are predictable. The EU Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger told the EU Parliament that ‘There is talk of an apocalypse and I think the word is particularly well chosen.’

9

Was it? From what perspective?

So should Prudence’s husband have his CT scan? Would Prudence willingly stand a mile and a half from the Hiroshima bomb?

When people can look at comparable risks of exposure and regard one with utter horror but the other with approval, it might reveal that they are wildly irrational. Or does it rather reveal the limitations of probability as a measure of what danger is really about? Perhaps it simply encourages us to be clear why we really dislike things. To reply, ‘well obviously, because of the danger’ is a convenient argument, but sometimes not the whole truth.

20

SPACE

W

HEN THE BODY

of the stowaway hit the street, it sounded like a slamming door. He was frozen, which, all things considered, was probably for the best. But Prudence didn’t think so.

‘What if it had hit the conservatory?’ she said.

‘He, not it,’ Norm said. ‘Anyway, it didn’t.’

‘Norm, we sit there for breakfast. Pansy was

there

,

on her own

, on

that

chair, when … my God …’

‘Pru, the chance …’

‘Chance?! What were the chances of a dead body falling?

*

I mean, one [she raised her finger] out of the air; two, [another finger] to the ground, all the way; three, in Basingstoke; four, in the first place? Tell me that. And what happened? It happened. Well, if that can happen … You see. Every morning, we sit in that conservatory having breakfast. Next thing you know there’s a stiff Algerian in your Weetabix. It only takes one, you know.’

But a few days later it was Norm’s turn to look up anxiously.

‘You see, asteroids could be it,’ he said to Prudence, turning his teacup. It was a lottery, entirely, the chance of the big hit by one among millions of possible hits in an infinity of cosmic debris.

He turned the cup again. It wasn’t fear of death that bothered him; more like working out the odds. One day something would fall from the sky, and the chance was both certain and invisible. It made him cross.

‘Oh I know,’ said Pru, ‘I’m the same with pigeons.’

‘It’s not calculable, the probability, not sensibly.’

‘Well it’s bloody amazing, the aim.’

‘And the damage … the carnage, potentially.’

‘The cleaning, that’s for sure.’

‘Think of London.’

‘Quite.’

‘I’m coming round to some form of general-purpose defence.’

‘An umbrella?’

‘Technically speaking, an umbrella, yes.’

‘Always have one.’

‘Despite the cost.’

‘Trivial by comparison, surely?’

‘Absolutely.’

Later, as night fell, he looked up, hands on hips. For a long time he stared, a man alone under the stars, looking for answers. Where was it, the one with our number on it, out in the vastness, the blackness, the unknown? Somewhere, coursing. Except coursing was hares. So not hares. Silent and unseen, towards earth’s small plot in this … this … fathomless … this universe, this little O. The path, the uncluttered, no cluttered, the cluttered path through space of the asteroid hurled by a God of limitless thunder that one day would end all human ends was one possible, improbable path … possibility among countless other possibly … possible path probabilities, probably. One lump, grain – because it’s all relative – in a boundless storm, yes, and the two trajectories of earth and rock predestined by infinite lottery to meet by a cosmic whisker. It was the ultimate doom, reckoning, fate and embodiment of all fear.

*

‘So,’ said Kelvin in the pub later, ‘what’s it mean for house prices?’

‘?’

‘Practicalities, Norm, come on.’

Email: Prudence to Norm