The Only Thing Worth Dying For (50 page)

Read The Only Thing Worth Dying For Online

Authors: Eric Blehm

Tags: #Afghan War (2001-), #Afghanistan, #Asia, #Iraq War (2003-), #Afghan War; 2001- - Commando operations - United States, #Commando operations, #21st Century, #General, #United States, #Afghan War; 2001-, #Afghan War; 2001, #Political Science, #Karzai; Hamid, #Afghanistan - Politics and government - 2001, #Military, #Central Asia, #special forces, #History

Although Amerine recommended Alex for the Air Force Cross, the Air Force downgraded the award to a Silver Star because Alex’s actions were not deemed sufficiently heroic for that high an honor. Most of the men of ODA 574 were recommended for Silver Stars, but these requests were also downgraded, to Bronze Stars—the same awards given to the members of Fox’s headquarters staff. ODA 574 lobbied for the posthumous presentation of Silver Stars to Dan and JD, which were given to their families.

Brent and Victor were the only members of the team who remained on ODA 574 for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Brent later went on to become a team sergeant. Both are still with 5th Group.

Ken was sent to a different team in 5th Group, retiring in 2002. No disciplinary action was taken following his removal from ODA 574.

Wes returned to 5th Group but left the military after serving a tour in Iraq. He traveled the world as a contracted soldier, going back to Afghanistan in 2006 to work as one of President Karzai’s personal bodyguards. The first Green Beret shot in combat in the War on Terror, Wes still has his uniform shirt with the bullet hole.

Mag spent almost two years in hospitals, undergoing surgery and rehab for his traumatic brain injury and to combat a number of other injuries that included loss of part of his vision and part of his left hand, and severe left-side paralysis. Eventually he relearned to walk and dress himself, but he continues to suffer from kidney failure, mood disorders, and migraines. He refused to receive his Bronze Star and

Purple Heart in a hospital, waiting until he was able to return home and stand at attention in a ceremony at the 5th Group block at Fort Campbell. He now participates in Paralympics competitions, recently swimming a mile in open water in a triathlon. In 2008, he discovered the four-leaf clover his daughter had given him in 1990; it had slipped behind some files in a fire vault in his home.

Lloyd Allard retired from the Army after two tours in Iraq. In 2007, he and a staff sergeant from 5th Group, Robbie Doughty—who had lost both legs in Iraq—opened a Little Caesars pizza franchise given to them as part of the Little Caesars Veteran Program, which helps returning veterans transition back into their communities.

Cubby Wojciehowski became a Special Forces warrant officer. He named his son Daniel, after Dan Petithory—“a good, strong name,” he said.

Nelson Smith became one of the youngest team sergeants in 5th Group, leading an ODA on multiple tours in Iraq. The other members of the headquarters element—including Terry Reed, Chris Fathi, and Chris Pickett—recovered from their wounds; most returned to 5th Group and took part in the invasion of Iraq.

Chris Miller was involved in the planning for and invasion of Iraq. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 2006 after two tours in Iraq, taking command of Fox’s old battalion when Fox moved on. Bob Kelley was given an early promotion to lieutenant colonel and selected to command 1st Battalion, 5th Group, in 2003. Under his leadership, 1st Battalion created and led multi-ethnic Iraqi Special Operations units that have played a pivotal role in that war. While many consider him the mastermind behind the unconventional warfare campaign in Afghanistan, he credits the other True Believers, saying, “Success has many fathers.”

The Air Force investigation into the friendly-fire bombing on December 5 took almost two years to complete, during which time a rumor circulated around 5th Group that Bolduc had directed the bomb. While the investigative board concluded that Fox’s lax

supervision—cited as “[i]nadequate command and control interaction between the on-scene ground commander and the terminal attack controllers”—contributed to the accident, the report ultimately blamed Air Force TACP Jim Price, citing procedural errors. Though Price knew he was at fault, the findings of the board never seemed accurate to him.

1

The GPS device that Price used was never recovered, making it impossible to review the data, but after returning to 5th Group, he was able to re-create the steps he had taken on December 5 and determine exactly what had gone wrong. He had initially tested the Viper—calibrated to store multiple cloud ceilings—by lasing the ground in front of him, a location that was stored instead of being discarded as he had expected. When Price called in the JDAM, he inadvertently used that stored location, directing the bomb to a grid only a few feet ahead of where he was standing on the Alamo. Had he double-checked the target coordinates on the military GPS with his personal GPS, as he had on the previous air strikes, he would have caught the error.

Price served a tour in Iraq as a fully qualified JTAC and controlled his final combat air strike south of Baghdad in April 2004. He retired from the Air Force and now teaches “joint fires and close air support” courses for a U.S. Army school, dedicating his life to helping others avoid the same type of tragic mistake he made.

The penetrating JDAM bomb killed three Americans and wounded twenty-five; it killed an estimated fifty Afghans, including Bari Gul, Bashir, and most of their men. If Price had chosen a surface-detonating JDAM, it’s likely that nobody on or near the Alamo would have survived the blast. The crew of the B-52 was cleared of any fault in the bombing incident but would forever remember that horrible morning and the seven-hour flight from Shawali Kowt back to the island of Diego Garcia for its haunting silence.

Investigations into both friendly-fire bombings—of Queeg’s headquarters on November 26, 2001, and of Fox’s headquarters less than two weeks later—failed to point out that in both incidents, battalion headquarters directed the air strikes in spite of the presence of ODAs who should have been calling in the bombs. No punitive measures were taken for either accident.

During the planning for Operation Iraqi Freedom, Mulholland subtly acknowledged the mistakes made in Afghanistan by making sure that headquarters staff C-teams were utilized according to doctrine, as headquarters providing command-and-control support to combatants, not as combatants themselves. Now a lieutenant general, Mulholland became the commander of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Fox and Bolduc were both promoted and presented medals for their actions in Afghanistan. Bolduc was later selected to command a battalion and received an early promotion to full colonel. Fox was given command of a garrison at Fort Bragg. A few months after the bombing, Fox was asked by PBS’s

Frontline

whether he second-guessed his decision to call in the strikes on December 5. “Every day,” he said. “I’m sure that there was something I could have done better. There was something I could have done to prevent it. Was that cave that important that day? But it’s just something I’m going to have to live with for the rest of my life.”

General James Mattis, who had refused to send rescue helicopters until hours after the bomb hit, went on to command the 1st Marine Division during the invasion of Iraq. There, in a highly publicized, extremely unusual, and arguably ironic action, he relieved a subordinate, Colonel Joe Dowdy, for hesitating in battle while leading his regiment’s drive to Baghdad.

On December 22, 2001, Steve Hadley was invited by Karzai to escort him and his family from Kandahar to Kabul to attend his inauguration ceremony as interim leader. En route, Karzai presented him with his battle flag—the national flag of Afghanistan that he had kept with him throughout the mission with ODA 574—as a personal token of his appreciation for the AFSOC rescue efforts. Hadley still serves as an active-duty USAF pilot-physician and is a renowned trauma expert.

The Air Force Special Operations Command awarded just a few basic air medals for the rescue mission. The vast majority of the officers and enlisted men flying on Knife 03 and 04 that day, including Hadley, were not recognized for their exceptional actions on December 5. But there is not a man from ODA 574 or Fox’s headquarters staff who is not

indebted to them—as well as the members of Delta and the CIA whose medical skills saved many lives before the helicopters arrived.

Casper, Charlie, Zepeda, Mr. Big, and the other spooks who had worked with Karzai went on to other assignments in the Clandestine Services. Casper became the chief of station for the CIA in Afghanistan for the years following 2001. In many accounts of the war, he is referred to as “Greg” or “Bush,” supposedly because of his likeness to George W. Bush.

Since becoming president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai has faced growing criticism about his inability to stop corruption within his government and to curb the rise of the Taliban. The reason, according to some Karzai proponents, is the lack of sufficient security forces from the United States and NATO. The shift in focus from Afghanistan to Iraq disheartened many of the men of ODA 574 who had hoped to see Task Force Dagger’s brisk victory in 2001 followed by a final coup d’état against the Taliban and al-Qaeda. Instead, they watched international support for Karzai wane.

James Dobbins, now the director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center at the RAND Corporation, told me just prior to the August 2009 presidential election in Afghanistan, “I think Karzai was the ideal man for his time, a figure around whom the international community and the Afghan population could unite, as they did. It’s not clear that someone chosen as a peacemaker is equally ideally suited to the job of war making. As yet, however, no more suitable or probable candidate for that position has emerged, making it quite possible that Karzai will have to continue to lead his country through the current conflict.”

2

After Amerine was medevaced to Germany on December 8, 2001, an Army Public Affairs officer asked him to participate in a press conference. Half deaf, with shrapnel still embedded in his leg and his boots stained with the blood of his men, he spoke to the reporters gathered there: “One thing I want to stress is that I do not want to allow this incident to overshadow the good work that my detachment and the

headquarters element did over the course of the time we worked in Afghanistan. The mission we were given was a hard one, and I’m proud of the soldiers I served with, both the Americans and Afghans. All the men are heroes, and they should be remembered for what they accomplished during their time in Afghanistan and not as victims in an accident.”

Amerine left 5th Special Forces Group in April 2002 to teach in the social sciences department at West Point, his alma mater, and was promoted to major. Before leaving Fort Campbell, he had taken one last stroll around the 5th Group block. He passed the anti-aircraft gun from the Gulf War, the old barracks that housed ODA 574’s team room, and the ISOFAC where the men had awaited their deployment to Afghanistan.

Eventually, he arrived at Gabriel Field and walked slowly around the newest additions to the Trees of the Dead: three saplings honoring Master Sergeant Jefferson Donald Davis, Sergeant First Class Daniel Henry Petithory, and Staff Sergeant Brian Cody Prosser—the first Special Forces soldiers killed in the War on Terror.

His final thought as he walked away:

Too much damn shade on this field

.

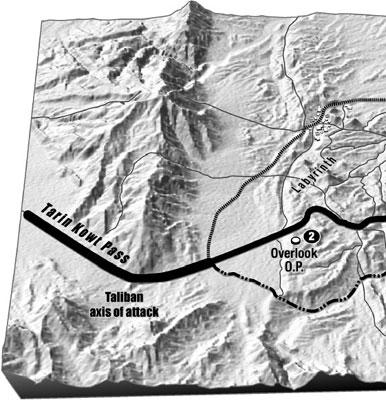

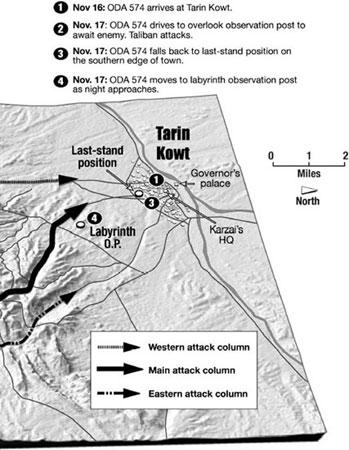

Map of Tarin Kowt:

Nov. 16-17, 2001

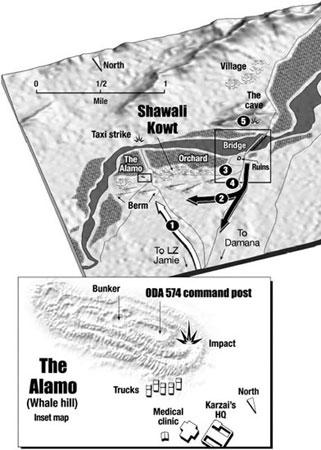

Map of Shawali Kowt:

Dec. 3-5, 2001