The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan (34 page)

Read The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan Online

Authors: Michael Hastings

Combat outpost JFM

There was an edgy, animalistic feel to the place. A group of about ten soldiers gathered around a mortar pit like it was a campfire, the focal point of the small base. There were two large guard watchtowers, a sandbagged headquarters made from plywood, a few trailers for bunk beds, and a line of Porta-Johns. One soldier was sitting in a foldout chair next to the mortar tube, getting his head shaved; the others talked among themselves. No one made eye contact.

Duncan and I were more or less ignored. We threw our bags into one of the trailers, which looked like a shipping container. They were called CHUs (pronounced

choos

), for containable housing units.

A Short Timer’s calender inside JFM

Lieutenant Graham Williams commanded the platoon at JFM. He wasn’t impressed by our presence, either. He

gave me a tour of the base. I climbed up one of the guard towers behind him. He pointed off to a small house in the distance.

“That’s where Ingram got hit,” he said.

I wasn’t making much progress in my conversations with the soldiers. They clearly didn’t trust us, didn’t appreciate our being there. They were still reeling from the trauma of Ingram’s death ten days earlier and the frustration of a year at war. I felt I had to do something to gain their trust. I asked Williams if they were going on a patrol tonight. The lieutenant said yes. I asked if I could join them. He said I could if I wanted. He said he didn’t give a shit.

It was a strange reaction. Most of the time, a reporter on a patrol is welcomed, or at least the soldiers pretend to welcome him. But by this point in the tour, a reporter had just become a hassle, something else to worry about. They didn’t even bother worrying.

It got dark.

Staff Sergeant Kennith Hicks and Lieutenant Williams were going to lead the patrol. I slipped on my body armor and helmet and borrowed a pair of eye protection with clear lenses from one of the soldiers who was staying behind.

The soldiers gathered around Hicks for the pre-patrol briefing. Hicks stood about five feet nine and had close-cropped blond hair. He spoke in a language where

um

s and

uh

s were replaced by

fuck

s and

fucking

s.

“Obviously fucking threats are out there, dismounted,” he said. He mentioned Ingram without mentioning Ingram. “You all know what happened. You know what’s out there. You know what you’re coming up against. Be extremely fucking careful, look for markings on the ground.”

Lieutenant Williams added, “There’s no hurry. Scan the surface, look for hot spots. Make slow fucking movements. Don’t feel like you got to rush through there.”

“We should give out diseased blankets to them, like we did to the fucking Indians,” said one soldier.

“Fucking give them immunization but instead make it AIDS,” said another.

Leaving the patrol base, we crept along the Hesco barriers on a small footpath with a deep drop-off down to a muddy drainage ditch. We started walking down the road. The moon backlit the patrol through the overcast sky. I could make out each soldier clearly as they staggered themselves out, S-shaped, keeping enough distance between themselves so if one stepped on a mine, maybe only one would die.

We got about two hundred meters away when the soldiers took up position in the ruins of an abandoned house. I crawled up the wall and kneeled down on the second floor. It was white and gray, all crumbling rock, like an empty housing project from the world of the Flintstones. All the houses had the appearance of bunkers and combat positions, not homes—meant to kill or hide, not to live in.

Lieutenant Williams saw something move a hundred meters away at another house. Cars had been driving up and pulling away over the last hour, more activity at the house than they’d seen in weeks.

Across the field and down the road, a flashlight flicked on and off.

The light flashed again.

“There’s somebody in there,” Lieutenant Williams said. “In Ingram’s house.”

He crawled down from where we were kneeling on the second floor. He waved Hicks and another soldier over to him.

They started to walk down the road.

They disappeared.

THWUMP, THWUMP.

The sound of illumination mortar rounds fired from the base.

The sky lit up.

I looked to my left and right, checking who was next to me. Four silhouettes outlined: three soldiers and an Afghan interpreter, standing and kneeling on the second floor and staring out to where Williams and Hicks had vanished.

The wind started to pick up. There was lightning in the distance. A bad storm was moving in and the dust mixed with the darkness. It was hard to see.

There was no sound coming from Ingram’s house.

I waited for the explosion. For the automatic rifle fire to follow. For the adrenaline to dump and the yelling to start. For our entire universe, three hundred meters of limited visibility, to stop all motion, then hit warp speed, the rhythm of violence and death.

There was just silence.

Three figures came back down the road. Williams waved us down from the second floor. We climbed down. They hadn’t found anything in Ingram’s house.

“We have no medevac support because of the weather, so we’re going back,” Williams said.

We walked back to the base, slowly, watching our step. The patrol lasted one hour and ten minutes.

The soldiers threw off their gear. The tension eased. The patrol was over and nobody was dead. They gathered around the mortar pit. I started to talk to them.

Twenty-one-year-old Private Jared Pautsch told me his story. His brother Jason had been killed in Baghdad in 2007. Jared spoke at his funeral. Jared signed up to get revenge. To kill the fuckers who killed his brother. He told me that he thought counterinsurgency was bullshit. I asked him what he thought of McChrystal coming down to speak with them tomorrow.

He laughed.

“Fuck McChrystal.”

He told me that the men blamed McChrystal and his rules of engagement for Ingram’s death. The unit had asked for months to destroy the house that Ingram had been killed in, but they kept getting the permission to do so denied. They were told that they weren’t allowed to destroy the home because it would anger the local Afghan population. The soldiers

argued that it wasn’t a house—it was a fighting position. Nobody lived there. The Taliban just used it to fight and hide bombs.

Pautsch started talking about Ingram. He’d been there when he died.

On April 17, 2010, Arroyo led the squad into the house. Arroyo and Pautsch went one way; Ingram and the unit’s medic went the other. An explosion of brown dust. Ingram had stepped on an IED, a small landmine. The military had a new acronym for them, VOIED—victim operated improvised explosive device.

Ingram was bleeding heavily.

It took thirty minutes for the medevac helicopter to arrive. Ingram was “packaged up” and put on the bird, the soldiers said.

In Arroyo’s e-mail to McChrystal, he had said Ingram’s last words were about McChrystal. I told this to Pautsch.

Pautsch laughed. Arroyo, he said, was taking poetic license.

“More water, more morphine,” Pautsch said. “Those were some of his last words.”

I told him that Arroyo had written that McChrystal had inspired him.

“Ha, shit, did Arroyo write that? That’s funny. Ingram thought all this COIN stuff was bullshit, too. Maybe he did start to look up to McChrystal, but he sure as fuck didn’t tell me about it.”

Pautsch pulled a small laminated card from his pocket. It was the rules of engagement they’d been given.

“Look at this,” he said. It had a list of rules that the soldiers were supposed to follow.

One said: “Patrol only in areas that you are reasonably certain that you will not have to defend yourself with lethal force.”

“Does that make any fucking sense?” Pautsch asked me.

It didn’t make much sense. Asking infantrymen to patrol where they weren’t going to get shot at was like asking cops to patrol in places where there was no crime.

“We should just drop a fucking bomb on this place,” Pautsch said. “You sit and ask yourself, What are we doing here?”

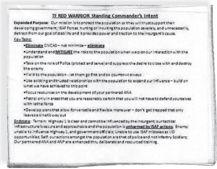

Rules of Engagement for JFM

Hicks agreed. “My guys keep asking me: What the fuck is the point?”

Hicks explained why he thought the rules of engagement had become so watered down: Because the battalion commander, Andersen, had kept getting his ass chewed out for killing civilians, he’d sent out guidelines that were even more restrictive than what McChrystal had proposed. The guidelines 1st Platoon were given were a way for the higher-ups to cover their asses—to avoid having civilian casualty incidents that could get them in trouble with ISAF HQ in Kabul.

“Ingram was a real fucking success story,” Hicks said. Hicks served three combat tours, including two in Ramadi. “He had so much fucking potential. He always made everybody laugh, was willing to learn. He was a good fucking soldier. I mean, this is war, we could get fucking blown up sitting here talking right now, fucking rocket could drop on our fucking heads. Fuck, when I came over here and heard that McChrystal was in charge, I thought we could get our fucking gun on. I get COIN. I get all that.

McChrystal comes here, explains it, it makes sense. But then he goes away on his bird, and by the time his directives get passed down to us through Big Army, they’re all fucked up either because somebody is trying to cover their ass, or because they just don’t understand themselves. But we’re fucking losing this thing.”

After talking for a few more hours, I headed to my trailer to sleep. Around midnight, there was a loud boom. More outgoing mortar rounds from the mortar pit.

The next morning, I woke up, brushed my teeth with bottled water, and grabbed a coffee.

At around 0830, the gates to JFM opened up again. McChrystal’s convoy of MRAPs rolled in. Two Afghan soldiers were in the way. One American soldier threw rocks at them, yelling at them to move. “Those fucking Afghans just walk around faded all the time,” the soldier said, meaning they were high.

The plan was for McChrystal to speak with the senior NCOs and officers.

The younger enlisted men smoked cigarettes down by a garbage burning pit.

McChrystal walked by me, flanked by Captain Duke Reim.

“Hey Mike,” Reim said. “Lucian, your photographer friend, told me to fucking watch out for you,” he said.

McChrystal looked up, a flash of panic on his face as he walked by.

Charlie Flynn jumped out of the MRAP.

“Duncan, Mike, come over here,” he said.

Duncan and I walked over to him.

“Tell me what’s going on here, how they are feeling,” he asked.

“The men are in high spirits,” Duncan told him. “They are excited that The Boss is down here.”

I was stunned. I wasn’t on the staff. It wasn’t my job to explain to them what was actually going on. But he’d asked for my opinion. I decided to answer diplomatically.

“Uh, I think they’re pretty upset by the rules of engagement,” I said. “Frustrated, you know, and they just lost Ingram—”

Duncan interrupted. “I wouldn’t say that. They feel like they’ve had some setbacks, but I wouldn’t say they are upset.”