The Origins of AIDS (11 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

Furthermore, at the time it was generally considered unwise for a man to marry outside his own ethnic group, and the shortage of women was worse in some of the tribes, such as the Basuku and the Bayaka. These two ethnic groups were migrant workers who would walk all the way to Léo (two or three weeks to get there, two or three weeks to come back), where they spent six to nine months before returning to their villages where the women stayed.

In 1955, there were 9.4 Bayaka men and 16 Basuku men in Léo for each woman of the same tribe. Conversely, the

Baluba,

Bapoto,

Bakula,

Batetela and

Basonge had, against all odds, an excess of adult females and were certainly overrepresented

among the free

women. The differences between ethnic groups were even more extraordinary when looking only at the currently unmarried. There were 2.5, 1.9 and 1.2 unmarried women for each unmarried man among the Bapoto

, Basonge

and Batetela respectively. For the Baluba and Bakula, the situation was complicated: an excess of males among the bachelors, but 3 to 5 women for each man among the divorced or widowed. At the other extreme, 47 unmarried Bayaka men competed for each unmarried woman. For the Basuku, this ratio was infinite: there were 3,070 unmarried men, and not a single unmarried woman! There must have been a corresponding heterogeneity in the ethnic distribution of men and women involved in the sex trade

.

64

In 1955, there were 9.4 Bayaka men and 16 Basuku men in Léo for each woman of the same tribe. Conversely, the

Baluba,

Bapoto,

Bakula,

Batetela and

Basonge had, against all odds, an excess of adult females and were certainly overrepresented

among the free

women. The differences between ethnic groups were even more extraordinary when looking only at the currently unmarried. There were 2.5, 1.9 and 1.2 unmarried women for each unmarried man among the Bapoto

, Basonge

and Batetela respectively. For the Baluba and Bakula, the situation was complicated: an excess of males among the bachelors, but 3 to 5 women for each man among the divorced or widowed. At the other extreme, 47 unmarried Bayaka men competed for each unmarried woman. For the Basuku, this ratio was infinite: there were 3,070 unmarried men, and not a single unmarried woman! There must have been a corresponding heterogeneity in the ethnic distribution of men and women involved in the sex trade

.

64

As a proxy for the cumulative incidence of STDs which often cause infertility, 35% of women aged forty-five years or over living in Léo in 1955 had never had a child, compared to 20% for the whole country. It is remarkable that the proportion of infertile women was lower among the younger cohorts: only 16% of those aged twenty-five to thirty-four had never given birth. This might reflect a higher incidence of STDs in the distant past, and perhaps a preferential migration towards Léopoldville of women repudiated by their husbands because they could not produce offspring.

Prostitution was driving infertility but infertility was also driving prostitution

.

60

Prostitution was driving infertility but infertility was also driving prostitution

.

60

History then accelerated the urbanisation process. Around the time of independence, the number of jobless men in Léo increased dramatically. In 1955, only 6% of male adults were unemployed. In the years immediately before independence, in the context of strong nationalist fervour, Belgian authorities relaxed the previously stringent restrictions on the movements of individuals and the unemployment rate swelled to 19% in 1958 and 29% by the end of 1959, a process made worse by an economic recession. The Belgian government tried to repatriate the redundant workers to rural areas, especially after the anticolonial riots of January 1959. Cash bonuses were offered to the unemployed who chose to go back to their home villages. These measures did not work, as political events were unfolding much faster than anybody had predicted. Five days after the country became independent on 30 June 1960, a mutiny broke out among rank-and-file soldiers, which spread like wildfire. Chaos ensued. Following massive migrations to the capital, the closure of several companies and the departure of many Europeans, the unemployment rate shot up to 49% at the end of 1960.

45

,

60

,

62

,

65

45

,

60

,

62

,

65

Throughout the post-independence troubles, Léopoldville remained rather peaceful and safe. The population of its peripheral areas increased eleven-fold over just two years, from 31,458 in 1959 to 358,308 in 1961. Many came from the

Kwilu-Kwango region, east of Léo, where an insurrection led to much instability. After paying a token fee to the traditional land owners who had been dispossessed decades earlier by the government or private companies, they occupied large tracts of land near the recently inaugurated

Ndjili international airport as well as in the

Kisenso,

Makala and

Selembao districts. Squatting was encouraged by the emerging political parties as a way of repossessing tribal land. For tens of thousands of Congolese, this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get a free, or almost free, plot of land in the capital.

45

,

65

,

66

Kwilu-Kwango region, east of Léo, where an insurrection led to much instability. After paying a token fee to the traditional land owners who had been dispossessed decades earlier by the government or private companies, they occupied large tracts of land near the recently inaugurated

Ndjili international airport as well as in the

Kisenso,

Makala and

Selembao districts. Squatting was encouraged by the emerging political parties as a way of repossessing tribal land. For tens of thousands of Congolese, this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get a free, or almost free, plot of land in the capital.

45

,

65

,

66

Thus, from a city of wage earners, many of whom worked for large companies, Léo became a city of the unemployed, who out of necessity tried to make a living in the informal sector, or became ‘parasites’ of relatives with a regular income. Consumer goods of all kinds were retailed in very small quantities, and the modest benefits of petty trade became a major force in the redistribution of wealth. By 1963, 70% of the income of school teachers was spent on food, and it is likely that this percentage was even higher for those without a regular income. Léopoldville was renamed Kinshasa in 1966, after the name of one of the pre-colonial villages: ‘Léo’ became ‘Kin’.

Over the decade that followed independence, its population increased three-fold, to 1.3 million in 1970, when the unemployment rate reached 70%, and doubled again to 2.7 million in 1984. It is currently thought to be somewhere between 8 and 9 million.

67

–

69

Over the decade that followed independence, its population increased three-fold, to 1.3 million in 1970, when the unemployment rate reached 70%, and doubled again to 2.7 million in 1984. It is currently thought to be somewhere between 8 and 9 million.

67

–

69

The gender imbalance progressively disappeared after independence. At the end of 1967, a census in Kinshasa showed that the male/female ratio was near unity for those under the age of thirty, while above this threshold there were 1.45 men for each woman. This normalisation of the sex ratio was related to two factors. First, more and more of the inhabitants of Kinshasa were born locally, attenuating the effect of the preferential migration of males. Second, many of the recent arrivals had fled their own region due to civil strife, and in such circumstances there was less of a difference between men and women, in contrast with the earlier economic migrations where the pull factor was stronger on men. These forces implied that eventually the sex ratio of the overall population of Kinshasa would get close to one, which it did. In Brazzaville, this

ratio reached unity in 1974, and remained close to equilibrium

thereafter

.

46

,

70

–

72

ratio reached unity in 1974, and remained close to equilibrium

thereafter

.

46

,

70

–

72

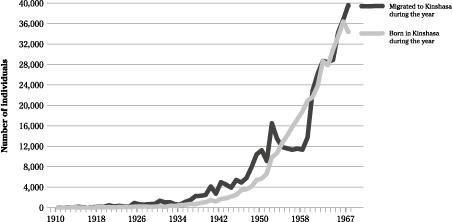

The graphic in

Figure 7

illustrates the fluctuating patterns of migration into Kinshasa as well as its relationship to the number of people born in the city. It was based on the 1967 survey, and therefore those migrants who did not stay or died were not counted (which means that the number of migrants in earlier years was substantially underestimated compared to more recent periods). It shows the strong migrations experienced during and after WWII, a temporary decrease during the recession of the late 1950s, and then a huge increase immediately after independence. During these same periods the number of births in Kinshasa increased steadily so that by the mid-1950s it was about equal to the number of migrations

.

Figure 7

illustrates the fluctuating patterns of migration into Kinshasa as well as its relationship to the number of people born in the city. It was based on the 1967 survey, and therefore those migrants who did not stay or died were not counted (which means that the number of migrants in earlier years was substantially underestimated compared to more recent periods). It shows the strong migrations experienced during and after WWII, a temporary decrease during the recession of the late 1950s, and then a huge increase immediately after independence. During these same periods the number of births in Kinshasa increased steadily so that by the mid-1950s it was about equal to the number of migrations

.

Figure 7

Migrations and births in Léopoldville–Kinshasa.

Migrations and births in Léopoldville–Kinshasa.

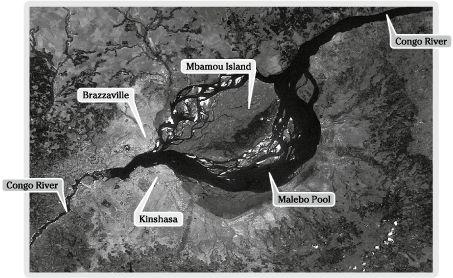

The links between Brazzaville and Léopoldville have been so strong for such a long time that they are in essence two components of a single conurbation, and this should be taken into account when we assemble the puzzle at the end of this book. Their geographic proximity is illustrated in the satellite photograph shown in

Figure 8

. At this point, the Congo is six kilometres wide. Most of the intercity traffic was carried by a company called

FIMA, from the names of its two Italian owners. FIMA operated a dozen boats of different sizes, including a

large one that could take automobiles, built by the Léopoldville shipyard. A regular ticket cost 25 francs, and there was a never-ending queue at the counter from early morning till mid-afternoon, with two or three departures each hour

. In addition, it was possible to cross the Congo in dugout canoes to visit relatives, trade various goods, avoid payment of taxes or conscription, be forgotten for a while after a brush with the law, etc. One just had to hire a fisherman for an hour

.

73

,

74

Figure 8

. At this point, the Congo is six kilometres wide. Most of the intercity traffic was carried by a company called

FIMA, from the names of its two Italian owners. FIMA operated a dozen boats of different sizes, including a

large one that could take automobiles, built by the Léopoldville shipyard. A regular ticket cost 25 francs, and there was a never-ending queue at the counter from early morning till mid-afternoon, with two or three departures each hour

. In addition, it was possible to cross the Congo in dugout canoes to visit relatives, trade various goods, avoid payment of taxes or conscription, be forgotten for a while after a brush with the law, etc. One just had to hire a fisherman for an hour

.

73

,

74

Figure 8

Satellite photograph of Kinshasa and Brazzaville, early twenty-first century.

Satellite photograph of Kinshasa and Brazzaville, early twenty-first century.

During the post-war era, for a musician to be considered truly successful, he had to perform regularly on both sides of the river, and popular music, which was completely out of the control of the European colonists, became a further unifying factor between the twin cities. Starting in 1949, football games between sponsored teams of Léopoldville and Brazzaville were held regularly, and thousands of supporters could travel to the other side to cheer on their own team. Ideas were also exchanged, and the relative freedom and less blatant racism of Brazzaville led many visitors from Léo to realise that their own situation was no longer acceptable. Some of these migrations were more permanent, and already in the post-war years Léo had the largest population of Moyen-Congo nationals after Brazzaville. The extent of this interpenetration was revealed in times of crisis. In August 1964, in

the midst of a dispute with the leftist government of

Congo-Brazzaville, the

Tshombe government of Congo-Léopoldville forcibly expelled from its capital all nationals of the former country. Over just a few days, 100,000 individuals crossed the river to the safety of Brazzaville. Later, as the economic situation of Zaire deteriorated during

Mobutu’s corrupt and incompetent dictatorship, mass migrations occurred mostly the other way. By the end of the 1980s 300,000 Zaireans were thought to be living in

Brazzaville

.

73

the midst of a dispute with the leftist government of

Congo-Brazzaville, the

Tshombe government of Congo-Léopoldville forcibly expelled from its capital all nationals of the former country. Over just a few days, 100,000 individuals crossed the river to the safety of Brazzaville. Later, as the economic situation of Zaire deteriorated during

Mobutu’s corrupt and incompetent dictatorship, mass migrations occurred mostly the other way. By the end of the 1980s 300,000 Zaireans were thought to be living in

Brazzaville

.

73

There, the largest city had always been the port of Douala. Possibly because it was a mandated territory, there was little attempt to limit the movement of women to the cities. Compared to Yaoundé, Douala’s demographic boom occurred earlier, immediately after WWII. Its population stabilised around 40,000 in 1936–46, and then shot up to 100,000 in the early 1950s and to 120,000 in 1957. The male/female ratio varied between 1.2 and 1.35 during WWII, increasing to 1.7 during the post-war period when Douala attracted many male

migrants, but quickly decreased to 1.2 in 1958.

75

migrants, but quickly decreased to 1.2 in 1958.

75

Yaoundé was established by the Germans in 1889 as a trading post. In 1916, it was the meeting point of the French and British armies that took Kamerun from the Germans. Five years later, Yaoundé rather than Douala was chosen as the political capital of Cameroun Français, because it was more central, cooler and more comfortable for Europeans, but also because it was deemed safer should the Germans try to return. While Douala remained the economic metropolis, Yaoundé became a quiet city of civil servants, with only 6,500 inhabitants in 1933. From 29,000 in 1952, its population increased more rapidly with the post-war economic boom, to 54,000 inhabitants five years later. There was a large influx of men, while the women followed a few years later. The male/female ratio was as high as 3.1 in 1955, quickly declining to 1.3 in 1957. After Cameroun became independent, the population of Yaoundé increased from 70,000 in 1960 to 300,000 twenty-five years later, while its male/female ratio remained around 1.2

.

75

–

76

.

75

–

76

Thus, in all urban centres located near the habitat of the

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzee, a gender imbalance resulted from the population policies of the colonial powers, and from the very nature of these booming towns

which attracted male migrants in search of a better life. This excess of males was more severe, for a longer period of time, in Léopoldville. In the

next chapter

we will see how various types of prostitution emerged to satisfy the sexual needs of these lonely men, the perfect breeding ground for the sexual amplification of HIV-1.

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzee, a gender imbalance resulted from the population policies of the colonial powers, and from the very nature of these booming towns

which attracted male migrants in search of a better life. This excess of males was more severe, for a longer period of time, in Léopoldville. In the

next chapter

we will see how various types of prostitution emerged to satisfy the sexual needs of these lonely men, the perfect breeding ground for the sexual amplification of HIV-1.

Other books

The Arctic Patrol Mystery by Franklin W. Dixon

Fangs And Fame by Heather Jensen

Victoria & Abdul by Shrabani Basu

Uncharted by Hunt, Angela

Dream of You by Kate Perry

The Long Cosmos by Terry Pratchett

The Sleepover Club Bridesmaids by Angie Bates

Where Love Has Gone by Harold Robbins

A Thousand Kisses Deep by Wendy Rosnau

Capture Me by Anna Zaires, Dima Zales