The Origins of AIDS (4 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

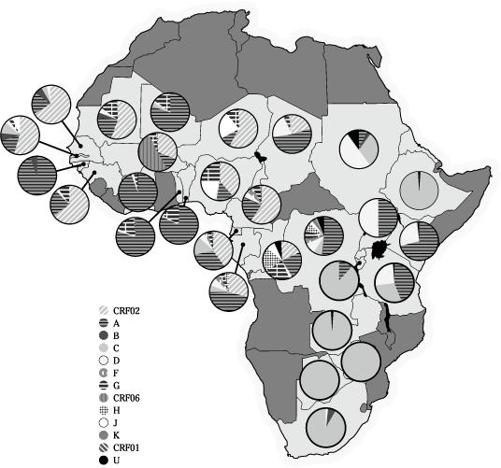

Map 2

Genetic diversity of HIV-1 in sub-Saharan Africa. The circles show the distribution of HIV-1 subtypes in various countries (U stands for unknown).

Genetic diversity of HIV-1 in sub-Saharan Africa. The circles show the distribution of HIV-1 subtypes in various countries (U stands for unknown).

Adapted from Peeters.

45

45

Within central Africa, however, there are differences between countries, which help us to track past events. In Cameroon, the CRF02_AG recombinant is by far the predominant subtype, as in

Nigeria to the north and Gabon and Equatorial Guinea to the south. This means that most of the HIV-1 transmission occurred relatively recently in these countries, without excluding the possibility that the initial case occurred there

.

53

–

56

Nigeria to the north and Gabon and Equatorial Guinea to the south. This means that most of the HIV-1 transmission occurred relatively recently in these countries, without excluding the possibility that the initial case occurred there

.

53

–

56

In the Central African Republic, there is a strong preponderance of subtype A

. In

Chad, a country not inhabited by the

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

chimpanzee, there is diversity but the distribution differs:

subtype A represents only 20% of isolates, while 40% are recombinants. This suggests that the virus disseminated there later than in the DRC.

57

,

58

. In

Chad, a country not inhabited by the

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

chimpanzee, there is diversity but the distribution differs:

subtype A represents only 20% of isolates, while 40% are recombinants. This suggests that the virus disseminated there later than in the DRC.

57

,

58

HIV-1 isolates obtained in 1997 from Kinshasa,

Bwamanda and

Mbuji-Mayi (all in DRC) were characterised. In Kinshasa, by descending order these were subtypes A (44%), D (13%), G (11%), H (10%), F (6%), K (3%), J (4%) and C (2%), while 8% could not be properly subtyped. Of note, only one subtype B strain was found, from a patient in Bwamanda in the

Equateur region.

This broad distribution of subtypes proved similar to what was measured retrospectively in samples collected in Kinshasa in the mid-1980s by

Projet Sida: HIV-1 diversity in Kinshasa twenty-five years ago was far more complex than among strains currently found in any other parts of the world!

59

,

60

Bwamanda and

Mbuji-Mayi (all in DRC) were characterised. In Kinshasa, by descending order these were subtypes A (44%), D (13%), G (11%), H (10%), F (6%), K (3%), J (4%) and C (2%), while 8% could not be properly subtyped. Of note, only one subtype B strain was found, from a patient in Bwamanda in the

Equateur region.

This broad distribution of subtypes proved similar to what was measured retrospectively in samples collected in Kinshasa in the mid-1980s by

Projet Sida: HIV-1 diversity in Kinshasa twenty-five years ago was far more complex than among strains currently found in any other parts of the world!

59

,

60

Only recently has HIV-1 diversity in Congo-Brazzaville been evaluated on a large number of isolates, obtained mainly in Brazzaville. A pattern similar to that of Kinshasa was found: a predominance of A and G but few CRF02_AG recombinants and no subtype B. So in the final analysis, the two Congos are the countries with by far the greatest diversity of HIV-1 subtypes. This implies that the oldest epidemic did in fact start in the DRC and Congo-Brazzaville

.

61

.

61

The genetic diversity of HIV-1 in a given location is influenced not only by how long it has been there, but also by how efficiently it propagated. An HIV-1 strain producing only one case of secondary infection every five years would present fewer variations after fifty years compared to the same strain which, introduced into another environment, would have generated a secondary case every three months, with each secondary case in turn producing a tertiary case every three months, and so on. The more people are infected, the more copies of the virus are produced each day, which increases the number of mutations and differentiation into subtypes. In practice, what the great genetic diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa and Brazzaville means is that for the first time the virus found in this large urban area conditions conducive to its dissemination on a scale that enabled it to flourish and differentiate, after an initial phase of stagnation or very slow multiplication, which could have occurred elsewhere in any of the countries inhabited by its simian source

.

.

It is still a mystery why subtype B remained rare in central Africa, where it represents only 0.2% of all HIV-1 infections, but spread so

successfully into the Americas and Western Europe. Presumably, chance (

the founder effect) played a major role, depending on whether a given subtype was introduced into some mechanism of amplification, sexual or otherwise, which gave it the initial boost after which it could disseminate slowly but effectively.

successfully into the Americas and Western Europe. Presumably, chance (

the founder effect) played a major role, depending on whether a given subtype was introduced into some mechanism of amplification, sexual or otherwise, which gave it the initial boost after which it could disseminate slowly but effectively.

2

The source

All kinds of trees

The source

So, HIV-1 originated from central Africa. But then, one may ask, why central Africa? The answer, as we will see, is because this region corresponds to the habitat of the simian source of the virus.

Our closest relativesChimpanzees are the closest relatives of humans, sharing between 98 and 99% of their genome with us, and are considered the most intelligent non-human animal. Chimpanzees and humans shared a common ancestor and are thought to have diverged between four and six million years ago. In fact, chimpanzees are so close to humans that it was recently proposed to move them into the genus

Homo

. Long-term studies in the

Gombe reserve of

Tanzania revealed that, like humans, chimpanzees have their own personalities. Some are gentle, others are more aggressive. Some have a good relationship with their parents or other members of the troop while others are loners. Some have a strong maternal instinct, others do not. This marked individualisation and their ability to laugh are what make chimpanzees most like humans. Rather than reacting predictably and instinctively to a given situation, chimpanzees show intelligence and spirit and experience all kinds of emotions.

1

–

3

Homo

. Long-term studies in the

Gombe reserve of

Tanzania revealed that, like humans, chimpanzees have their own personalities. Some are gentle, others are more aggressive. Some have a good relationship with their parents or other members of the troop while others are loners. Some have a strong maternal instinct, others do not. This marked individualisation and their ability to laugh are what make chimpanzees most like humans. Rather than reacting predictably and instinctively to a given situation, chimpanzees show intelligence and spirit and experience all kinds of emotions.

1

–

3

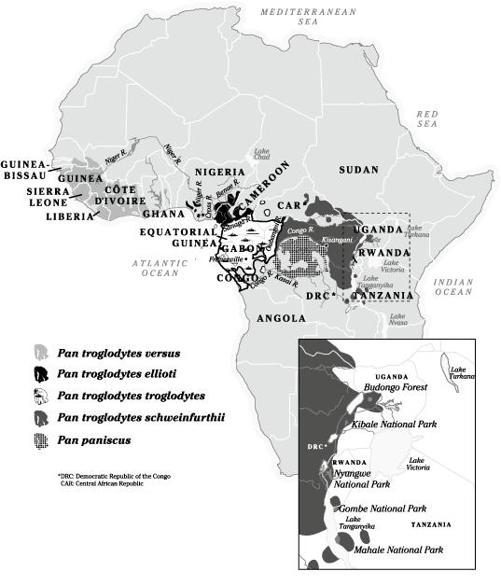

According to current taxonomy, there are two species:

Pan troglodytes

, the common chimpanzee, and

Pan paniscus

, the

bonobo. Based on analyses of mitochondrial DNA (DNA that comes solely from the mother), there are now four subspecies of

Pan troglodytes

:

Pan troglodytes verus

(western chimpanzee),

Pan troglodytes ellioti

(Nigerian chimpanzee, until recently

P.t. vellerosus

),

Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

(eastern chimpanzee) and

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

(central chimpanzee) (

Map 3

).

4

Pan troglodytes

, the common chimpanzee, and

Pan paniscus

, the

bonobo. Based on analyses of mitochondrial DNA (DNA that comes solely from the mother), there are now four subspecies of

Pan troglodytes

:

Pan troglodytes verus

(western chimpanzee),

Pan troglodytes ellioti

(Nigerian chimpanzee, until recently

P.t. vellerosus

),

Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

(eastern chimpanzee) and

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

(central chimpanzee) (

Map 3

).

4

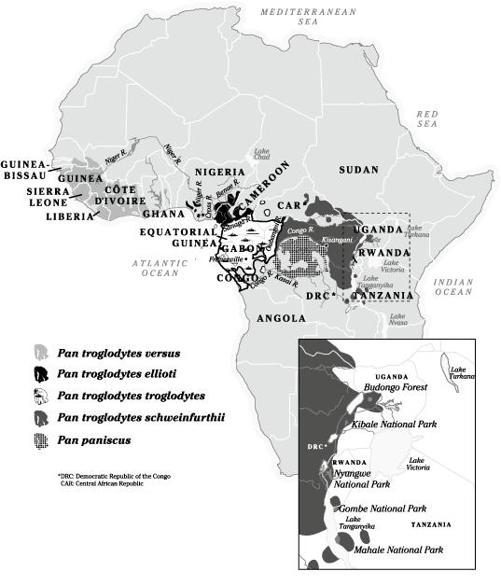

Map 3

Distribution of the four subspecies of

Pan troglodytes

and the

Pan paniscus

bonobo.

Distribution of the four subspecies of

Pan troglodytes

and the

Pan paniscus

bonobo.

Chimpanzees are poor swimmers, so that large rivers like the

Cross,

Sanaga,

Ubangui and Congo became natural boundaries between the

habitat of various species and subspecies.

Pan troglodytes verus

(total population in 2004: between 21,300 and 55,600, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature) inhabits West Africa, from southern

Senegal to the west bank of the Cross River in

Nigeria;

most of its population is now found in

Guinea and

Ivory Coast

.

Pan troglodytes ellioti

(total population: 5,000–8,000) is found from east of the

Cross to the

Sanaga River in Cameroon, its southern boundary.

Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

(total population: 76,400–119,600) inhabits mostly the DRC, east of the Ubangui and north of the Congo rivers

, but its range extends into the

Central African Republic, southern

Sudan and eastwards to

Uganda,

Rwanda and

Tanzania.

5

Cross,

Sanaga,

Ubangui and Congo became natural boundaries between the

habitat of various species and subspecies.

Pan troglodytes verus

(total population in 2004: between 21,300 and 55,600, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature) inhabits West Africa, from southern

Senegal to the west bank of the Cross River in

Nigeria;

most of its population is now found in

Guinea and

Ivory Coast

.

Pan troglodytes ellioti

(total population: 5,000–8,000) is found from east of the

Cross to the

Sanaga River in Cameroon, its southern boundary.

Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

(total population: 76,400–119,600) inhabits mostly the DRC, east of the Ubangui and north of the Congo rivers

, but its range extends into the

Central African Republic, southern

Sudan and eastwards to

Uganda,

Rwanda and

Tanzania.

5

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

(total population: 70,000–116,500) inhabits an area south of the Sanaga River in Cameroon and extending eastward to the Ubangui and Congo rivers

, spread over seven countries: southern Cameroon,

Gabon, the continental part of

Equatorial Guinea,

Congo-Brazzaville, a small area in the south-west of the Central African Republic, the

Cabinda enclave of Angola and the adjacent

Mayombe area of the DRC. The largest populations are found in

Gabon (27,000–64,000), where unfortunately they are rapidly declining, Cameroon (31,000–39,000) and

Congo-Brazzaville (about 10,000). Other countries have fewer than 2,000 each, with probably less than 200 in the DRC

. It is estimated that

P.t. troglodytes

and

P.t

.

schweinfurthii

diverged approximately 440,000 years ago

.

5

,

6

(total population: 70,000–116,500) inhabits an area south of the Sanaga River in Cameroon and extending eastward to the Ubangui and Congo rivers

, spread over seven countries: southern Cameroon,

Gabon, the continental part of

Equatorial Guinea,

Congo-Brazzaville, a small area in the south-west of the Central African Republic, the

Cabinda enclave of Angola and the adjacent

Mayombe area of the DRC. The largest populations are found in

Gabon (27,000–64,000), where unfortunately they are rapidly declining, Cameroon (31,000–39,000) and

Congo-Brazzaville (about 10,000). Other countries have fewer than 2,000 each, with probably less than 200 in the DRC

. It is estimated that

P.t. troglodytes

and

P.t

.

schweinfurthii

diverged approximately 440,000 years ago

.

5

,

6

Chimpanzee populations in the first half of the twentieth century were certainly higher than now, because there had been relatively little opportunity for human activities to disrupt the natural equilibrium of the species. Human populations were much smaller than today, with fewer hunters and fewer clients willing to purchase bush

meat. As an educated guess, some experts suggested that, combining all subspecies, there was around one million chimps in 1960. The subsequent decline was particularly severe for

P.t. verus

, and is generally attributed to the destruction of its habitat by increasing human populations who farmed or logged and hunted for bush meat, to diseases like

Ebola fever, and captures for medical experiments.

6

–

10

meat. As an educated guess, some experts suggested that, combining all subspecies, there was around one million chimps in 1960. The subsequent decline was particularly severe for

P.t. verus

, and is generally attributed to the destruction of its habitat by increasing human populations who farmed or logged and hunted for bush meat, to diseases like

Ebola fever, and captures for medical experiments.

6

–

10

The rest of this section will focus on the central

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzee, but the morphologic, demographic and behavioural differences between the four subspecies of

Pan troglodytes

are minor, at least for the non-expert.

P.t.troglodytes

chimps have a life expectancy of 40–60 years. An adult male weighs 40–70 kg, a female 30–50 kg. They live in rather loose communities (‘troops’) of 15 to 160 individuals, with a dominant male leader. When they reach sexual maturity, males generally remain in the community into which they were born, while females often join other

troops. This intuitive exogamy maintains the genetic diversity of the subspecies and avoids the potentially devastating effects of inbreeding.

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzee, but the morphologic, demographic and behavioural differences between the four subspecies of

Pan troglodytes

are minor, at least for the non-expert.

P.t.troglodytes

chimps have a life expectancy of 40–60 years. An adult male weighs 40–70 kg, a female 30–50 kg. They live in rather loose communities (‘troops’) of 15 to 160 individuals, with a dominant male leader. When they reach sexual maturity, males generally remain in the community into which they were born, while females often join other

troops. This intuitive exogamy maintains the genetic diversity of the subspecies and avoids the potentially devastating effects of inbreeding.

Chimpanzees are largely diurnal. To sleep at night, each individual builds a nest in a tree, complete with a pillow, 9–12 metres above the ground, which is normally used only once. For this reason, scientists have used nests to estimate chimpanzee populations, based on counts by surveyors who walk on line transects through forested areas as a sampling method. Population density of

P.t. troglodytes

is generally between 0.1 and 0.3 km

2

. Most communities live in forested areas, and a minority in savannahs.

P.t. troglodytes

is generally between 0.1 and 0.3 km

2

. Most communities live in forested areas, and a minority in savannahs.

Chimpanzees are intensely territorial and most troops spend their entire lives within a 20–50 km

2

area. Adult males are aggressive, and spend much of their time patrolling their small territory. Males of one troop can form raiding parties to attack lone males (or couples) from other troops.

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzees usually have a hostile and violent attitude towards members of other communities. Among their

P.t. schweinfurthii

counterparts in

Tanzania, primatologists documented a war between two neighbouring communities which, after three years of attacks and killings, ended with the complete annihilation of the weaker troop.

1

,

11

–

13

2

area. Adult males are aggressive, and spend much of their time patrolling their small territory. Males of one troop can form raiding parties to attack lone males (or couples) from other troops.

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzees usually have a hostile and violent attitude towards members of other communities. Among their

P.t. schweinfurthii

counterparts in

Tanzania, primatologists documented a war between two neighbouring communities which, after three years of attacks and killings, ended with the complete annihilation of the weaker troop.

1

,

11

–

13

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzees are able to develop and use tools, mostly sticks to procure food (for instance, to dig out ants or termites or extract honey from hives). Unlike gorillas, chimpanzees are omnivorous, with a highly diversified diet consisting mostly of fruits, leaves, seeds, plants, insects and eggs, but they occasionally eat vertebrates, including monkeys, antelopes and warthogs.

chimpanzees are able to develop and use tools, mostly sticks to procure food (for instance, to dig out ants or termites or extract honey from hives). Unlike gorillas, chimpanzees are omnivorous, with a highly diversified diet consisting mostly of fruits, leaves, seeds, plants, insects and eggs, but they occasionally eat vertebrates, including monkeys, antelopes and warthogs.

An infant chimp spends the first five years of its life completely dependent on its mother. Like humans, they become progressively autonomous during adolescence, reaching sexual maturity at age 12–13. Chimpanzees are promiscuous, and most of their sexual activity takes place when the adult female is in heat and her vulva swells, which attracts the males, who copulate with her quickly, one after the other. As many as six different males may copulate with the same female in just ten minutes. Some males establish an exclusive relationship with a female of their choice, presumably for reproductive purposes, and take her on a ‘honeymoon’ far from the other chimpanzees. This usually only lasts for a week or two during which they copulate as often as five times a day. So while their behaviour limits the transmission of pathogens between troops, sexually transmitted infectious agents will easily

disseminate within a given troop once they have been successfully introduced.

disseminate within a given troop once they have been successfully introduced.

P.t. troglodytes

chimps have low fertility: on average, 800 matings occur for each conception. During their reproductive years (from age 14 to 40), females give birth to a mean of 4.4 babies, half of which die before reaching maturity. Each female has a lifetime reproductive success of only 2.3. A small increase in mortality, due to hunting or diseases, is sufficient to reduce this number to less than two and for the population to contract.

14

,

15

chimps have low fertility: on average, 800 matings occur for each conception. During their reproductive years (from age 14 to 40), females give birth to a mean of 4.4 babies, half of which die before reaching maturity. Each female has a lifetime reproductive success of only 2.3. A small increase in mortality, due to hunting or diseases, is sufficient to reduce this number to less than two and for the population to contract.

14

,

15

Like humans, chimpanzee communities are occasionally stricken by epidemics. In

Gombe, during an outbreak in the region’s human population,

poliomyelitis caused four deaths and left some chimpanzees permanently paralysed. Respiratory infections followed, also with fatal consequences. This reflects not just the communal nature of life among the chimpanzees, which have frequent and close contacts with other members of their troop, but also their biological similarity to humans, whose microbes can be transmitted to chimpanzees and vice versa

.

1

Gombe, during an outbreak in the region’s human population,

poliomyelitis caused four deaths and left some chimpanzees permanently paralysed. Respiratory infections followed, also with fatal consequences. This reflects not just the communal nature of life among the chimpanzees, which have frequent and close contacts with other members of their troop, but also their biological similarity to humans, whose microbes can be transmitted to chimpanzees and vice versa

.

1

We will now examine how it gradually became clear that one subspecies of chimpanzees was the source of HIV-1. But first, let us review quickly a science called phylogenetics. Phylogenetics uses nucleotide sequences to reconstruct the evolutionary history of various forms of life, including microbial pathogens. A ‘phylogenetic tree’ superficially resembles a genealogical tree. However, phylogenetic trees describe the relatedness between living organisms (and their classification) rather than ancestry. They measure the genetic distance between organisms, and identify the nearest relatives. Because ancestors are not available to be tested, ancestry is assumed rather than proven. Each division in the tree is called a ‘node’, the common ancestor of the organisms or the isolates identified to its right. After such branching, the organisms and their sequences evolve independently. The ‘root’ (at the extreme left) is the assumed common ancestor of all organisms in the tree. To construct a phylogenetic tree, molecular biologists compare the differences in nucleotide sequences of many isolates of putatively related organisms. This exercise is repeated for various genes; if the findings are the same for two or

three genes, scientists are confident that they have produced the right phylogenetic tree.

three genes, scientists are confident that they have produced the right phylogenetic tree.

An ‘isolate’ corresponds to a given pathogen obtained from one specific patient or animal at a specific point in time. If substantial laboratory work is done on any isolate, it will be given a name corresponding either to the initials of the patient, the name of the city or country where it was obtained or whatever the researcher decides to call it. Like children’s names, these names serve only one purpose, to distinguish isolates from each other.

For two isolates belonging to the same species, a greater degree of divergence, corresponding to a larger cumulative number of errors in replication, indicates that their common ancestor was further back in time compared to isolates with a lesser degree of divergence. This is like brothers and sisters, born of the same mother and father, being more similar to each other than distant cousins who only share, say, great-grandparents. In practice, phylogenetic trees tell us that certain viruses are closely related and have a relatively recent common ancestor (these are said to ‘cluster’), like brothers or first cousins, while for other viruses the relationship is similar to that of tenth cousins, whose common ancestors lived many generations ago

.

.

The first report of the isolation of a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) from a chimpanzee born in the wild came in 1989. This isolate, given the name SIV

cpz-gab1

, was obtained from a chimpanzee kept at the primate centre of

Franceville,

Gabon, where fifty chimps had been tested with assays used for the detection of anti-HIV antibodies in humans. Only two carried such antibodies; from one of them, the virus could be grown in cell culture, and its proteins were analysed. This chimpanzee, captured at six months of age, was four years old when the blood sample was obtained and seemed healthy despite presenting enlarged lymph nodes. Based on the crude methods available at the time, this SIV isolate was described as related although not identical to HIV-1. Phylogenetic analyses suggested that SIV

cpz-gab1

was closer to HIV-1 than to HIV-2 and to SIVs from African green monkeys, mandrills and other monkeys.

16

–

17

cpz-gab1

, was obtained from a chimpanzee kept at the primate centre of

Franceville,

Gabon, where fifty chimps had been tested with assays used for the detection of anti-HIV antibodies in humans. Only two carried such antibodies; from one of them, the virus could be grown in cell culture, and its proteins were analysed. This chimpanzee, captured at six months of age, was four years old when the blood sample was obtained and seemed healthy despite presenting enlarged lymph nodes. Based on the crude methods available at the time, this SIV isolate was described as related although not identical to HIV-1. Phylogenetic analyses suggested that SIV

cpz-gab1

was closer to HIV-1 than to HIV-2 and to SIVs from African green monkeys, mandrills and other monkeys.

16

–

17

It was not possible to isolate the virus from the second seropositive chimp, a two-year-old animal shot by hunters and that died of its wounds shortly after being brought to

Franceville for care. A few years later, thanks to technological advances, nucleic acid amplification was used on this chimp’s lymphocytes (which had been kept

frozen), in order to sequence parts of the viral genome. This isolate became known as SIV

cpz-gab2

. It was phylogenetically close to SIV

cpz-gab1

. In 1992, a third isolate (SIV

cpz-ant

) was obtained from Noah, a five-year-old chimpanzee captured in the wild and impounded by customs officers in Brussels upon illegal arrival from Zaire. His isolate was somewhat divergent from HIV-1 and from the two previous SIV

cpz

isolates.

18

–

20

Franceville for care. A few years later, thanks to technological advances, nucleic acid amplification was used on this chimp’s lymphocytes (which had been kept

frozen), in order to sequence parts of the viral genome. This isolate became known as SIV

cpz-gab2

. It was phylogenetically close to SIV

cpz-gab1

. In 1992, a third isolate (SIV

cpz-ant

) was obtained from Noah, a five-year-old chimpanzee captured in the wild and impounded by customs officers in Brussels upon illegal arrival from Zaire. His isolate was somewhat divergent from HIV-1 and from the two previous SIV

cpz

isolates.

18

–

20

In 1999, a fourth isolate, SIV

cpz-US

, was obtained from Marilyn, caught in the wild in an unknown African country and imported into the US as an infant in 1963. Marilyn was used as a breeding female in a primate facility until she died in 1985 at the age of twenty-six, after delivering still-born twins. During a survey of captive chimpanzees, Marilyn was the only one that was seropositive for HIV-1 antibodies. She had not been used in AIDS research, but had received human blood products between 1966 and 1969. During this early period, it is very unlikely that the blood products contained HIV-1, so there was a good chance that Marilyn had acquired her SIV

cpz

infection in Africa. SIV sequences were amplified from the spleen and lymph node tissues procured at

autopsy. Using mitochondrial DNA analyses, researchers identified the subspecies of chimpanzees from which this recent and the previous three isolates had been obtained.

21

–

22

cpz-US

, was obtained from Marilyn, caught in the wild in an unknown African country and imported into the US as an infant in 1963. Marilyn was used as a breeding female in a primate facility until she died in 1985 at the age of twenty-six, after delivering still-born twins. During a survey of captive chimpanzees, Marilyn was the only one that was seropositive for HIV-1 antibodies. She had not been used in AIDS research, but had received human blood products between 1966 and 1969. During this early period, it is very unlikely that the blood products contained HIV-1, so there was a good chance that Marilyn had acquired her SIV

cpz

infection in Africa. SIV sequences were amplified from the spleen and lymph node tissues procured at

autopsy. Using mitochondrial DNA analyses, researchers identified the subspecies of chimpanzees from which this recent and the previous three isolates had been obtained.

21

–

22

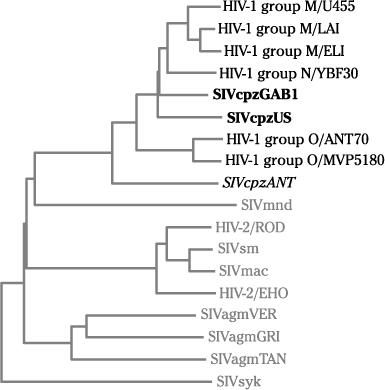

As could have been expected from the geographic distribution of

Pan troglodytes

subspecies, Noah (from Zaire) was a

P.t. schweinfurthii

while the other three, including Marilyn, were

P.t. troglodytes

. As illustrated in

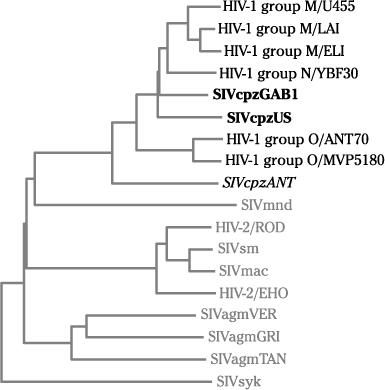

Figure 1

, phylogenetic analyses revealed that the three SIV isolates obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

were similar to each other, and similar to HIV-1 strains from humans, while Noah’s SIV

cpz-ant

diverged from these and lay outside this cluster, as did

HIV-2 and SIVs obtained from other non-human primates.

Pan troglodytes

subspecies, Noah (from Zaire) was a

P.t. schweinfurthii

while the other three, including Marilyn, were

P.t. troglodytes

. As illustrated in

Figure 1

, phylogenetic analyses revealed that the three SIV isolates obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

were similar to each other, and similar to HIV-1 strains from humans, while Noah’s SIV

cpz-ant

diverged from these and lay outside this cluster, as did

HIV-2 and SIVs obtained from other non-human primates.

Figure 1

Phylogenetic analysis showing the relationship between SIV

cpz-US

and SIV

cpz-gab1

obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzees (bold) and isolates from humans infected with HIV-1 (group M, group N, group O). The SIV

cpz

isolates obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

cluster within the HIV-1 isolates, while SIV

cpz-ant

obtained from a

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimpanzee (italics) lies outside. Other SIV isolates obtained from monkeys and human isolates of HIV-2 lie further away.

Phylogenetic analysis showing the relationship between SIV

cpz-US

and SIV

cpz-gab1

obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

chimpanzees (bold) and isolates from humans infected with HIV-1 (group M, group N, group O). The SIV

cpz

isolates obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

cluster within the HIV-1 isolates, while SIV

cpz-ant

obtained from a

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimpanzee (italics) lies outside. Other SIV isolates obtained from monkeys and human isolates of HIV-2 lie further away.

Adapted from Gao.

21

21

Thus, naturally occurring SIV

cpz

strains fell into two related but highly divergent, chimpanzee subspecies-specific, lineages: one for

P.t. troglodytes

and another for

P.t. schweinfurthii

. It was bravely concluded that

P.t. troglodytes

was the primary source of

HIV-1 group M and its natural reservoir, and that there had been host-dependent evolution of SIV

cpz

in chimpanzees resulting in

P.t. troglodytes

and

P.t. schweinfurthii

being infected with different lineages of SIV. Scientists could not rule out the possibility that other chimpanzee subspecies, especially

P.t. schweinfurthii

, could have transmitted their viruses to humans. This prudence was justified because a single isolate of SIV

cpz

from

P.t. schweinfurthii

was

available. It was possible that in the future other isolates of SIV

cpz

, more similar to the human isolates of HIV-1, might be found in

P.t. schweinfurthii

. Additional isolates of SIV

cpz

were later obtained from captive

P.t. troglodytes

in

Cameroon, some of which were similar to those human HIV-1 isolates from the same country, reinforcing the view that HIV-1 originated in chimpanzees.

21

,

23

cpz

strains fell into two related but highly divergent, chimpanzee subspecies-specific, lineages: one for

P.t. troglodytes

and another for

P.t. schweinfurthii

. It was bravely concluded that

P.t. troglodytes

was the primary source of

HIV-1 group M and its natural reservoir, and that there had been host-dependent evolution of SIV

cpz

in chimpanzees resulting in

P.t. troglodytes

and

P.t. schweinfurthii

being infected with different lineages of SIV. Scientists could not rule out the possibility that other chimpanzee subspecies, especially

P.t. schweinfurthii

, could have transmitted their viruses to humans. This prudence was justified because a single isolate of SIV

cpz

from

P.t. schweinfurthii

was

available. It was possible that in the future other isolates of SIV

cpz

, more similar to the human isolates of HIV-1, might be found in

P.t. schweinfurthii

. Additional isolates of SIV

cpz

were later obtained from captive

P.t. troglodytes

in

Cameroon, some of which were similar to those human HIV-1 isolates from the same country, reinforcing the view that HIV-1 originated in chimpanzees.

21

,

23

Since this initial work was conducted mostly with chimpanzees which had been in captivity for some time, it was questionable whether the apes had acquired their SIV

cpz

naturally in the wild or artificially in their cages where they had been in contact with other primates. In the first

case, the puzzle was close to being solved while, in the second, researchers had ventured down the wrong track. Non-invasive technologies were then developed to measure the presence of SIV antibodies and nucleic acids among chimpanzees living in the wild using urine and faecal samples, since obtaining blood samples was neither feasible nor ethically acceptable (some animals may have been hurt or killed in the process). We can but admire the motivation and expertise of these researchers and especially their trackers, roaming through the forest looking for chimpanzee urine or stools, which they had to distinguish from those of other animals. Urine samples proved inferior to faeces and were abandoned.

cpz

naturally in the wild or artificially in their cages where they had been in contact with other primates. In the first

case, the puzzle was close to being solved while, in the second, researchers had ventured down the wrong track. Non-invasive technologies were then developed to measure the presence of SIV antibodies and nucleic acids among chimpanzees living in the wild using urine and faecal samples, since obtaining blood samples was neither feasible nor ethically acceptable (some animals may have been hurt or killed in the process). We can but admire the motivation and expertise of these researchers and especially their trackers, roaming through the forest looking for chimpanzee urine or stools, which they had to distinguish from those of other animals. Urine samples proved inferior to faeces and were abandoned.

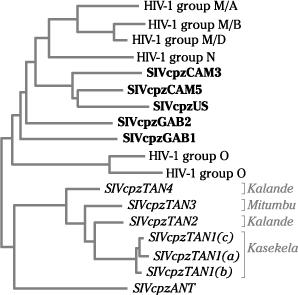

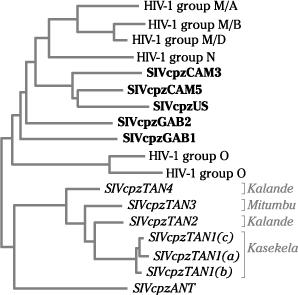

Among 100 wild

P.t. schweinfurthii

from

Uganda and Tanzania, only one was infected with SIV

cpz-tan1

. This isolate was similar to the previous SIV

cpz-ant

isolate from Noah, the Zairean

P.t. schweinfurthii

. More isolates were later found among

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimps in

Gombe, where SIV

cpz

prevalence was estimated to be around 20%. Phylogenetic analyses showed that these isolates clustered with SIV

cpz-ant

and diverged from the

P.t. troglodytes

isolates and from HIV-1 (

Figure 2

), confirming that

P.t. schweinfurthii

was not the source of HIV-1. Testing of additional

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimps from the Budongo forest of Uganda, the

Mahale park in Tanzania and the

Nyungwe reserve in

Rwanda (

Map 3

) failed to identify a single animal infected with SIV

cpz

. This heterogeneous distribution of SIV

cpz

, which has recently been mirrored in a study of

P.t. schweinfurthii

in the DRC, probably reflects the community structures of chimpanzee populations and their behaviour: they have few contacts with chimpanzees belonging to other communities, except during territorial fights or when adolescent females migrate to other troops. But once SIV

cpz

is successfully introduced into a community, there seems to be substantial transmission between its members, sexually or otherwise.

24

–

28

P.t. schweinfurthii

from

Uganda and Tanzania, only one was infected with SIV

cpz-tan1

. This isolate was similar to the previous SIV

cpz-ant

isolate from Noah, the Zairean

P.t. schweinfurthii

. More isolates were later found among

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimps in

Gombe, where SIV

cpz

prevalence was estimated to be around 20%. Phylogenetic analyses showed that these isolates clustered with SIV

cpz-ant

and diverged from the

P.t. troglodytes

isolates and from HIV-1 (

Figure 2

), confirming that

P.t. schweinfurthii

was not the source of HIV-1. Testing of additional

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimps from the Budongo forest of Uganda, the

Mahale park in Tanzania and the

Nyungwe reserve in

Rwanda (

Map 3

) failed to identify a single animal infected with SIV

cpz

. This heterogeneous distribution of SIV

cpz

, which has recently been mirrored in a study of

P.t. schweinfurthii

in the DRC, probably reflects the community structures of chimpanzee populations and their behaviour: they have few contacts with chimpanzees belonging to other communities, except during territorial fights or when adolescent females migrate to other troops. But once SIV

cpz

is successfully introduced into a community, there seems to be substantial transmission between its members, sexually or otherwise.

24

–

28

Figure 2

Phylogenetic analysis showing the relatively distant relationship between SIV

cpz

isolates obtained in Tanzania from

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimpanzees (italics) and SIV

cpz-ant

obtained from a

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimp from the DRC (italics), clearly separated from the HIV-1 group M isolates. The latter are close to SIV

cpz

isolates obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

(bold). HIV-1 group O lies outside the other HIV-1 isolates (in contrast to HIV-1 group N, which lies inside).

Phylogenetic analysis showing the relatively distant relationship between SIV

cpz

isolates obtained in Tanzania from

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimpanzees (italics) and SIV

cpz-ant

obtained from a

P.t. schweinfurthii

chimp from the DRC (italics), clearly separated from the HIV-1 group M isolates. The latter are close to SIV

cpz

isolates obtained from

P.t. troglodytes

(bold). HIV-1 group O lies outside the other HIV-1 isolates (in contrast to HIV-1 group N, which lies inside).

Adapted from Santiago.

26

26

SIV is non-existent among captive

P.t. verus

(the western chimpanzee), about 1,500 of which were tested and found to be uninfected. Surveys of wild

P.t. verus

and

P.t. ellioti

also failed to find a single case of SIV

cpz

infection. Why is SIV

cpz

absent within these two subspecies? Presumably, because SIVs were introduced into

P.t. troglodytes

and

P.t. schweinfurthii

only after these subspecies had diverged from

P.t. verus

and

P.t. ellioti

half a million years ago. Such a scenario would imply that there has been little contact between the subspecies ever since, which is possible since the large rivers of Africa constitute watertight

barriers

.

29

P.t. verus

(the western chimpanzee), about 1,500 of which were tested and found to be uninfected. Surveys of wild

P.t. verus

and

P.t. ellioti

also failed to find a single case of SIV

cpz

infection. Why is SIV

cpz

absent within these two subspecies? Presumably, because SIVs were introduced into

P.t. troglodytes

and

P.t. schweinfurthii

only after these subspecies had diverged from

P.t. verus

and

P.t. ellioti

half a million years ago. Such a scenario would imply that there has been little contact between the subspecies ever since, which is possible since the large rivers of Africa constitute watertight

barriers

.

29

Other books

The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Emmuska Orczy

A Christmas Bride by Hope Ramsay

Ajar by Marianna Boncek

La Vie en Bleu by Jody Klaire

Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare

Napoleon III and the French Second Empire by Roger D. Price

My Sweetest Sasha: Cole's Story (Meadows Shore Book 2) by Charles, Eva

The Husband Hunt by Lynsay Sands

Unhooking the Moon by Gregory Hughes

Holding on to Heaven by Keta Diablo