The Other Barack (25 page)

Authors: Sally Jacobs

Not everyone made it through the rigorous and highly competitive program. More than a few who found the heavy emphasis on math in the early 1960s not what they had expected cut their losses after two years and fled with a master's degree, widely considered by those left behind to be a consolation prize. Professor James Duesenberry regularly greeted his opening class in Money and Finance with the chilling observation: “In every entering class there are just so many

geniuses

,” he would say, taking a

long, slow look at the students listening intently to him. “I just don't know where they all go.”

19

geniuses

,” he would say, taking a

long, slow look at the students listening intently to him. “I just don't know where they all go.”

19

The first year was a slog of must-dos. There was economic theory with Ed Chamberlin, a department fixture who had made his name in the early 1930s with the publication of his theory of monopolistic competition, and macroeconomics taught by Robert Dorfman, a stern figure who was one of the department's earliest proponents of the mathematical trend. Statistics and economic history were also de rigueur. In their second year students were free to branch into areas of their own particular interest, with the realization that whatever they chose they would have to make a comprehensive presentation of several subject areas for their oral exams at the end of the year. If they passed their exams, they could then move on to pursue their dissertation.

Like the majority of his classmates, Obama had taken only a modest amount of math in his undergraduate years and was largely unprepared for the rigors of macroeconomics as it was being taught. He was an admirer of some of the pioneers of the emerging field, such as MIT's legendary Paul Samuelson, author of the largest-selling economics textbooks of its time,

Economics: An Introductory Analysis

, and Kenneth Arrow, who had coproduced a transformative mathematical proof of a general equilibrium, and Obama read their work closely. Although he managed to pass the department's math test in the first few months, he struggled to keep up with the weight of his coursework. In his letter to Sylvia Baldwin, his friend in Hawaii, Obama uncharacteristically conceded that things were getting “pretty rough.” “The competition here is just maddening,” Obama wrote. “In fact I have to read at least 12 books a week plus monographs, periodicals and professional journals, let alone the routine of school, the papers required and my own research on the theory I am trying to build. It really does keep me busy.”

20

Economics: An Introductory Analysis

, and Kenneth Arrow, who had coproduced a transformative mathematical proof of a general equilibrium, and Obama read their work closely. Although he managed to pass the department's math test in the first few months, he struggled to keep up with the weight of his coursework. In his letter to Sylvia Baldwin, his friend in Hawaii, Obama uncharacteristically conceded that things were getting “pretty rough.” “The competition here is just maddening,” Obama wrote. “In fact I have to read at least 12 books a week plus monographs, periodicals and professional journals, let alone the routine of school, the papers required and my own research on the theory I am trying to build. It really does keep me busy.”

20

Obama was so busy, in fact, that he had no time for either the public speaking or campus socializing that he had dallied in while in Honolulu. A month after Obama arrived, Dr. Ralph Bunche, who in 1950 was the first African American to win the Nobel Peace Prize and was an active supporter of the civil rights movement, spoke on campus and declared that not only was the Congo unprepared for independence, but also that many of the new African states were not ready for such a step. The same

argument had provoked Obama to loud fury two years earlier in Hawaii, but this time he said not a word in public. No admonishing letter to the

Crimson

. No pontificating on the granite steps above Cambridge Street. Nor was Obama one of the regulars at the coffee shop on the mezzanine at Littauer, where some of the heavyweights in the class like Thurow and Bowles regularly hung around noodling over multiple regression analysis and linear programming, not to mention debating the Vietnam War and the racial turbulence in the South. More often than not, Obama was in his cramped study carrel in the Littauer basement bent over the calculus problems that bedeviled him. The coffee klatch was a telling measure of the changes transforming the study of economics. The things that were cutting edgeâstructural imbalance, econometric forecasting models, game theoryâwere not so much in the textbooks as they were in the air. “The guys you saw there every day had a higher batting average, they just did better than the others,” explained Roger Noll, then a classmate and later a professor of economics at Stanford University. “The up-to-date conversation was going on in the lounge. That's where you were talking the new stuff. That's what kids do if you want to be at the forefront. You don't want to be Ken Galbraith, you want to be Ken Arrow.”

argument had provoked Obama to loud fury two years earlier in Hawaii, but this time he said not a word in public. No admonishing letter to the

Crimson

. No pontificating on the granite steps above Cambridge Street. Nor was Obama one of the regulars at the coffee shop on the mezzanine at Littauer, where some of the heavyweights in the class like Thurow and Bowles regularly hung around noodling over multiple regression analysis and linear programming, not to mention debating the Vietnam War and the racial turbulence in the South. More often than not, Obama was in his cramped study carrel in the Littauer basement bent over the calculus problems that bedeviled him. The coffee klatch was a telling measure of the changes transforming the study of economics. The things that were cutting edgeâstructural imbalance, econometric forecasting models, game theoryâwere not so much in the textbooks as they were in the air. “The guys you saw there every day had a higher batting average, they just did better than the others,” explained Roger Noll, then a classmate and later a professor of economics at Stanford University. “The up-to-date conversation was going on in the lounge. That's where you were talking the new stuff. That's what kids do if you want to be at the forefront. You don't want to be Ken Galbraith, you want to be Ken Arrow.”

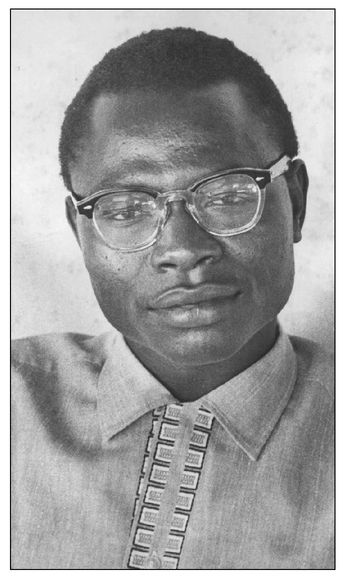

Barack H. Obama as a student in Hawaii. He was one of an elite group of young Kenyan men and women educated in America and charged with shaping the new Kenyan nation after independence was achieved in 1963.

The gravesite of Obama Opiyo, the great grandfather of President Barack Obama. The grave is located in Kanyadhiang where the president's father, Barack Hussein Obama, was born in 1936.

Kezia Obama, the first of Barack Obama's four wives, standing with their children Malik and Auma in the 1960s. Kezia now lives in Bracknell, England, while Malik and Auma live in Nairobi.

Barack H. Obama was recognized as an exceptionally bright student while still a young boy. Although he was accepted at the prestigious Maseno School in Western Kenya and studied there for several years, the principal grew annoyed at his challenging behavior and would not allow Obama to complete his studies.

Arthur Reuben Owino, a classmate and childhood friend of Obama's. Reuben recalls that Obama would often say, “You don't know what you are talking about. I am telling you what I know. âAnd then you would be arguing with him endlessly, endlessly.'”

Elizabeth “Betty” Mooney was an American literacy worker in Kenya in the late 1950s. In this photographâone of her favoritesâshe visits a Masai tribal community in 1959.

Mooney with Helen Roberts, an American literacy volunteer from California, standing near their car in Kenya. Mooney hired Obama as her secretary in 1958 and later paid for his first year's tuition at the University of Hawaii.

Obama and Mooney worked closely together for nearly two years, and she took many photographs of him. Here, he poses in front of the radio in her home in Nairobi.

Other books

Runaway Love by Washington, Pamela

Sneaky Pie's Cookbook for Mystery Lovers by Rita Mae Brown

Lions at Lunchtime by Mary Pope Osborne

B is for…

by

L. Dubois

Maddie's Big Test by Louise Leblanc

REPRESENTED by Meinel, K'Anne

Art Geeks and Prom Queens by Alyson Noël

The Malcontents by C. P. Snow

Anna In-Between by Elizabeth Nunez

The Mercenary by Cherry Adair