The Other Side of the Night (24 page)

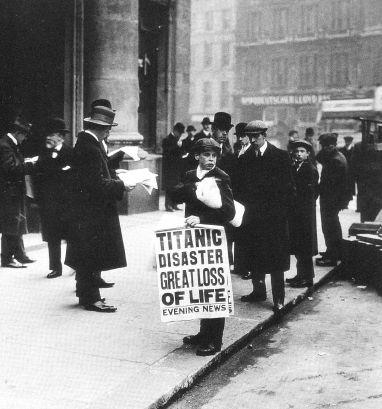

April 16, 1912. Newsboy Ted Parfett hawking editions of the London Evening News outside the White Star Offices on Trafalgar Square.

Part of the crowd lining the approaches to Cunard’s Pier 54 in New York, awaiting the arrival of the

Carpathia

.

The

Titanic

’s lifeboats, returned to the White Star Line in New York by the

Carpathia

. Within days of their arrival, the name

Titanic

was removed from each, and they were pressed into service on other White Star ships.

William Alden Smith, the junior United States Senator from Michigan, who chaired the Senate investigation into the

Titanic

disaster.

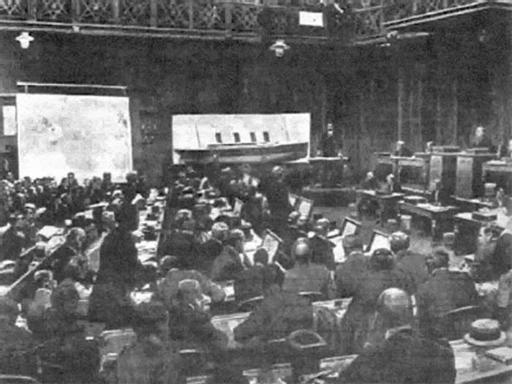

The Senate hearings in session in New York. Compared to the British Inquiry, the American investigation was a very informal affair.

Lord Mersey (right) on his way to one of the sessions of the British Inquiry, accompanied by his son.

The British Board of Trade Inquiry into the loss of the

Titanic

, held in the London Scottish Drill Hall.

Second Officer C.H. Lightoller and his wife Sylvia. Lightoller was the senior surviving officer from the

Titanic

’s crew.

Lord’s assumed air of calm authority for the most part seemed to give the lie to the rumors, although one comment he made seemed so unusual to the reporters of the

Boston Traveler

and the

Boston Evening Transcript

that both newspapers printed it. When pressed about the

Californian

’s position during the night of April 14–15, Lord refused, claiming such information was “state secrets.” He declined to show his log entries for that night, and informed the reporters that “the information would have to come from the company’s office.” Lord’s use of the term “state secrets” struck a jarring note at the time—it still does—for its hyperbole. The Leyland Line was a business, not a sovereign nation, and ships’ logs had always been, as a matter of common practice, if not actual law, available for public inspection at any time. The conclusion that there were entries made—or missing—of which Lord did not want the public to know was then, and remains, inescapable.

Nevertheless, the reporters took Lord at his word, and the story was buried on the inside pages of the handful of papers that carried it. The Boston press immediately turned its attention to the U.S. Senate investigation into the loss of the

Titanic

, which was just getting underway in New York. And so the strange mix of falsehood, deception, and fabrication about the events of April 15, 1912, which would come to surround Stanley Lord for the rest of his life, had begun.

The world might have never been the wiser had it not been for an obscure New England newspaper which featured an astonishing lead story in its April 23, 1912 edition. The Clinton, Massachusetts,

Daily Item

ran a banner headline which read:

CALIFORNIA [sic] REFUSED AID

Foreman Carpenter on Board this Boat Says Hundreds

Might Have Been Saved FROM THE TITANIC

Two men in Lord’s crew weren’t so easily dispatched by his casual dismissal of their veracity as he might have hoped. The first was the ship’s carpenter, James McGregor, who confided in his cousin, who lived in Clinton, that the

Californian

was close enough to the sinking

Titanic

to have actually seen the doomed liner’s lights and distress rockets. The account McGregor gave was so detailed, and tallied so closely with what had actually transpired on the

Californian

’s bridge and in her chartroom that there was no chance of his account being a fabrication.

According to McGregor, the officers on watch had seen an unknown ship to the south firing white rockets for the better part of an hour very early in the morning of April 15, and had duly reported their sightings to Captain Lord, who refused to take any action. It was shameful to McGregor to be associated, however indirectly, with such conduct, and his bitterness was palpable when he said, “The captain [Lord] will never be in command of the

California

[sic] again,” and that he would “positively refuse to sail under him again and that all of the officers had the same feeling.”

Not having any idea that Carpenter McGregor had already been talking to a reporter, but after reading his captain’s disparaging remarks in the Boston papers, Ernest Gill, one of the

Californian’

s assistant engineers, took a reporter and four fellow engineers to a notary public and swore out a lengthy affidavit, in which he maintained that he personally had seen a ship firing rockets just after midnight on April 15. Moreover, he claimed that the ship firing the rockets was no more than ten miles away, and that he had heard the

Californian’

s second officer saying that he too had seen the rockets, and that the ship’s captain had been told about them.

The affidavit was printed in its entirety on the morning of April 23 by the

Boston American

, which also wired a complete copy to Senator Smith in New York. Carpenter McGregor’s story appeared in the

Clinton Daily Item

the same day. For Smith, it was a remarkable turn of events, for he had, quite by accident, only the day before discovered that there had been an unknown ship within sight of the sinking

Titanic

which failed to respond to her distress signals. Smith was determined to find that ship.