The Oxford History of the Biblical World (25 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

The “peasants’ revolt” model and concomitant “Yahwistic revolution” have only partial explanatory power. If these farming villages were the product of this Yahwistic revolution, then how does one account for an almost equal number of “egalitarian” villages outside the confines of premonarchic Israel? They appear over a much wider landscape than even the most maximalist views of early Israel could include, ranging from Ammon to Moab and even into Edom, not to speak of those settlements within Canaan itself, where the ethnic identity of their inhabitants is in question.

It is unlikely that all these newly founded early Iron I settlements derived from a single source—whether of Late Bronze Age sheep-goat pastoralists settling down, or from disintegrating city-state systems no longer able to control peasants bent on taking over lowland agricultural regimes for themselves or pioneering new, “free” lands in the highlands. When one considers the widespread phenomenon of small agricultural communities in Iron Age I, it becomes even more difficult to explain it all by any hypothesis that would limit it to “Israelites” alone, as all three hypotheses do.

To draw the boundaries of premonarchic Israel so broadly as to include every settlement that displays the most common attributes of that culture (pillared farmhouses, collared-rim store jars, terraced fields, and cisterns), or to claim that all of these villages and hamlets on both sides of the Jordan are “Israelite” just because they share a common material culture, is to commit a fallacy against which the great French medieval historian Marc Bloch warned, namely, of ascribing a widespread phenomenon to a “pseudo-local cause.” A general phenomenon must have an equally general cause. Comparison with a similar but widespread phenomenon often undermines purely local explanations. Now that archaeologists have collected the kinds of settlement data that provide a more comprehensive pattern, the focus must be widened to include a more comprehensive explanation than the regnant hypotheses allow—whether they relate to an Israelite “conquest,” a “peasants’ revolution,” or “nomads settling down.”

It would be overly simplistic to draw the boundaries of premonarchic Israel so broadly as to ascribe the change in the settlement landscape to this historical force alone. This, of course, does not preclude the use of particularistic, historical studies to elucidate aspects of the larger process. Once the results of highland archaeology need not be accounted for by an exclusively “Israelite” explanation, one can then look at this well-documented polity as a case study within the larger framework.

From the changing settlement patterns in the Levant and elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean, it seems that the pattern of deep, structural change had more to do with the process of ruralization than revolution. In the Late Bronze Age there must have been acute shortages of labor in the city-states, where attracting and retaining agricultural workers was a constant problem. Evsey Domar

(Capitalism, Socialism, and Serfdom,

New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) has isolated a set of

interrelated variables that may help explain the proliferation of agricultural villages in frontier areas, where such entities as Israel, Moab, and Edom are already found in thirteenth-century

BCE

Egyptian sources. According to this formulation, only two of the three following variables can coexist within the same agricultural regime: free land, free peasants, and nonworking landowners. In the Late Bronze Age city-states, free land (in the highlands and marginal regions), nonworking landowners, and “serfs” existed. With the decline of some city-state systems, there would have been a centrifugal tendency for peasant farmers to settle beyond areas of state control, especially in the less accessible mountain redoubts.

So long as the Late Bronze Age markets and exchange networks were still operating, the sheep-goat pastoralists would have found specialization in animal husbandry a worthwhile occupation. However, with the decline of these economic systems in many parts of Canaan in the late thirteenth to early twelfth centuries

BCE

—when “caravans ceased and travelers kept to the byways” (Judg. 5.6)—the pastoralist sector, engaged in herding and huckstering, may also have found it advantageous to shift toward different subsistence strategies, such as farming with some stock-raising. This group undoubtedly formed part of the village population that emerged quite visibly in the highlands about 1200.

Especially in marginal “frontier” zones, the trend was toward decentralization and ruralization, brought about by the decline of the Late Bronze Age city-state and, in certain areas, of Egyptian imperial control. It is in this broader framework that we must try to locate the more specific causes that led to the emergence of early Israel.

Israel developed its self-consciousness or ethnic identity in large measure through its religious foundation—a breakthrough that led a subset of Canaanite culture, coming from a variety of places, backgrounds, prior affiliations, and livelihoods, to join a supertribe united under the authority of and devotion to a supreme deity, revealed to Moses as Yahweh. From a small group that formed around the founder Moses in Midian, other groups were added. Among the first to join was the Transjordanian tribe of Reuben, firstborn of the “sons of Jacob/Israel.” Later, this once powerful tribe was threatened with extinction (Deut. 33.6). But by then many others had joined the Mosaic movement scholars call Yahwism.

Nearly a century ago the historian Eduard Meyer traced the origin of Yahwism to the Midianites and to one of their subgroups, the Kenites. Recent archaeological discoveries in northern Arabia and elsewhere have revived and revised the “Midianite/Kenite” hypothesis, most elegantly expressed in the writings of the biblical scholar Frank M. Cross. A biography of Moses, the founder of Yahwism, cannot be written from the biblical legends that surround him. But several details in his saga, especially concerning the Midianites, seem to be early and authentic.

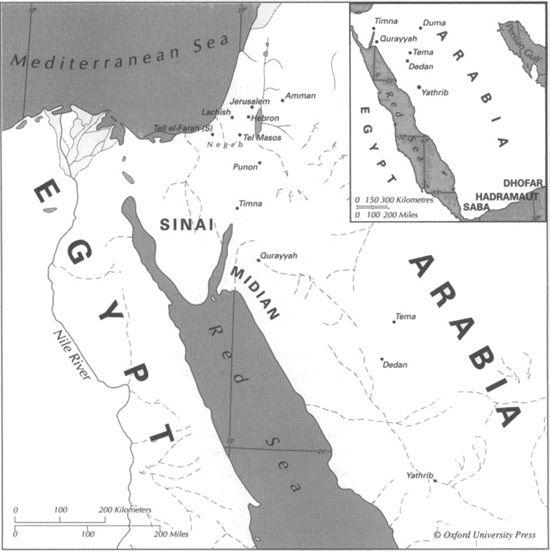

According to the epic source called J (Yahwist), Moses, after killing an Egyptian, fled from an unnamed pharaoh (perhaps Seti I) to the land of Midian. The heartland of Midian lay in the desert of rose-red mountains and plateaus above the great Rift Valley, east of the Gulf of Aqaba in northwestern Arabia. Medieval Arab geographers still referred to this region as the land of Midian; today it is known as the Hijaz. There Moses married the daughter of the Midianite priest Jethro (called Reuel or Hobab in other sources). During this initial episode in Midian, Moses experienced the theophany of Yahweh in the thornbush, which was blazing but was not consumed (Exod. 3.1-4.17).

Egypt, Sinai, Arabia, and the Land of Midian

After the Exodus from Egypt (probably during the reign of Rameses II), Moses returned with his followers to the same “mountain of God [

’elohim]”

in Midian, where he experienced a second theophany. In this episode Moses received the Ten Commandments and sealed the covenant between God

(’elohim)

and his people. Moses’ father-in-law, the priest of Midian, counseled him about implementing an effective judicial system among the Israelites, apparently based on one already in use among the Midianites (Exod. 18.13-27).

Jethro expressed his commitment to God

(’elohim)

through burnt offerings and sacrifices, and his solidarity with Moses and his followers through a shared meal “in the presence of God

[’elohim]”

(Exod. 18.12). Later Moses’ father-in-law helped guide this group through the wilderness as far as Canaan, but he declined to enter the

Promised Land, averring that he must return to his own land and to his kindred (Num. 10.29-32).

The traditions of benign relations between the Midianites and the Moses group reflect the period prior to 1100

BCE

, that is, before the era of Gideon and Abimelech, when the camel-riding and -raiding Midianites had become the archenemies of the Israelites (Judg. 6). The Midianites, like the Kenites, the Amalekites, and the Ishmaelites, disappear from biblical history by the tenth century

BCE

. It strains credulity to think that traditions about Moses, the great lawgiver and hero who married the daughter of the priest of Midian, were created during or after these hostilities.

Early Hebrew poetry suggests that the “mountain of God,” known as Horeb (in the E and D sources) and as Sinai (in the J and P sources), was located in the Arabian, not the Sinai, Peninsula. When Yahweh leads the Israelites into battle against the Canaanites in the twelfth-century Song of Deborah, the poet declares:

When you, Yahweh, went forth from Seir,

When you marched forth from the plateaus of Edom,

Earth shook,

Heaven poured,

Clouds poured water;

Mountains quaked;

Before Yahweh, Lord of Sinai,

Before Yahweh, God of Israel.

(Judg. 5.4-5; my translation)

Likewise in the archaic “Blessing of Moses”:

Yahweh came from Sinai,

He beamed forth from Seir upon us,

He shone forth from Mount Paran.

(Deut. 33.2; my translation)

And the same locale is given for Yahweh’s mountain home in Habakkuk 3:

God came from Teman,

The Holy One from Mount Paran….

He stood and he shook earth,

He looked and made nations tremble.

Everlasting mountains were shattered,

Ancient hills collapsed,

Ancient pathways were destroyed….

The tents of Cushan shook,

Tent curtains of the land of Midian.

(Hab. 3.3-7; my translation)

The tribesmen of Cushan were already encamped on the southeast border of Palestine in the early second millennium

BCE

, according to Middle Kingdom texts from Egypt. Later they were absorbed into the confederation of Midianites.

The epic traditions concerning Moses and the Midianites occur in story time between the Exodus from Egypt and the conquest of Canaan. The setting for these encounters on or near the “mountain of God” is connected with Edom, Seir, Paran,

Teman, Cushan, and Midian. There, in the Arabian, not the Sinai, Peninsula, Yahweh is first revealed to Moses, and it is from there that the deity marches forth to lead the nascent Israelites into battle, according to the earliest Hebrew poetry.

In historical time the benign relations between Midianites and Israelites should be set before 1100

BCE

, a period that also coincides with the floruit of “Midianite ware” (see below) and the presence of pastoralists in the region. The Egyptians of the New Kingdom included those tent-dwellers under the general rubric

Shasu.

Among their territories southeast of Canaan mentioned in the lists of Amenhotep III, one is designated the “land of the Shasu: S‘rr,” probably to be identified with Seir; another is known as the “land of the Shasu:

Yhw3,”

or Yahweh.

Until the enmity between Israelites and Midianites, exemplified in the wars of Gideon, dominated their relations, the two groups were considered kin, offspring of the patriarch Abraham: Israelites through Isaac, son of the primary wife, Sarah, and Midianites through Midian, son of the secondary wife or concubine, Keturah, whose name means “incense.” From Moses on, Midianites were also linked to Israelites by marriage to the founder of Yahwism.

All of this changed dramatically during the period of the judges. The about-face in attitude and policy toward the once-friendly Midianites is nowhere more vividly portrayed than in the polemic against the worship of Baal of Peor in Moab. In the J summary of the event (Num. 25.1-5), the Israelites are depicted as fornicators, whoring after the “daughters of Moab” and their deity Baal of Peor. Apparently a plague interrupted the festivities, and to ward it off the leaders of the Israelites “who yoked [themselves] to Baal of Peor” were executed. In the P account (Num. 25.6-18), Phinehas, who represents the later priestly household of Aaron, calls into question the genealogical charter of the priestly household of Moses and challenges the legitimacy of this dynasty of priests. When Phinehas finds a notable scion of the Israelites copulating with a notable daughter of the Midianites within the sacred precincts of the tent-shrine or tabernacle, the Aaronide priest skewers them both with a single thrust of his lance.

In the lineage of Abraham in Genesis, Keturah’s “sons” represent tribes and peoples trafficking in goods from Arabia (Gen. 25.1-4). Midianites and Ishmaelites settle in the land of Havilah (25.18), through which one of four rivers of Eden flows, a land rich in gold, bdellium, and carnelian (Gen. 2.11-12). Another river of paradise flows around the land of Cush (2.13), or Cushan, whose descendants include not only Havilah but also Seba/Saba/Sheba (Gen. 10.7; 1 Chron. 1.9).