The Oxford History of the Biblical World (58 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Ahaz’s son Hezekiah (727–698

BCE

; this is an alternate chronology to that used in

Chapter 6

) came to the throne in Jerusalem just about the time that Samaria embarked on the path of rebellion against Assyria that would eventually lead to its demise. After several encounters and a lengthy siege, Shalmaneser V (727–722) brought Samaria to its knees in the winter of 722. Only in 720, however, was the city’s rebellious military and political leadership finally subdued by Sargon II (722–705); he retook the now largely destroyed city, deported its population, and organized the territory into an Assyrian province. Sargon then moved down the coast and fought off an Egyptian corps that had arrived at Raphia at the gateway to the northern Sinai Peninsula, razing the town and carrying off thousands.

Jerusalem during the Eighth and Seventh Centuries

BCE

The kingdom of Judah was spared the direct effects of the Assyrian onslaught on Israel, but the harsh measures meted out were not lost upon Hezekiah, who for the present adopted the policy of compliance with the vassal demands of Assyria that had been adopted by his father, Ahaz, less than a decade earlier. Yet despite the tax and tribute payments—which must have been onerous (even though no records survive of the amounts involved)—the kingdom of Judah seems to have enjoyed the benefits of association with an imperial power. Judah after all bordered the Philistine entrepôts on the southern Mediterranean coast, the transshipping hub of the Arabian trade that passed through the Negeb desert. Hezekiah amassed great wealth, a process fostered by a sweeping reorganization of his kingdom. Newly constructed or refortified

royal store-cities gathered in the produce of herd and field, and in the capital state reserves of spices and aromatic oils and of silver and gold, not to mention the well-stocked arsenal, won international renown. Evidence of this vital economic and military activity can be found in the many jar handles impressed with stamp seals, which have been unearthed at dozens of sites in Judah. The seals consist of the phrase

belonging to the king

(in Hebrew,

Imlk),

the name of one of four administrative centers (Socoh in the Shephelah, Hebron in the hill country, Ziph in the Judean wilderness, and Mamshet [pronunciation uncertain] in the Negeb), and the royal insignia, the two-winged solar disk or the four-winged beetle that Judah’s kings had borrowed from Egypt. The storage jars on which these sealings appear presumably contained provisions that had been dispensed from the royal stores.

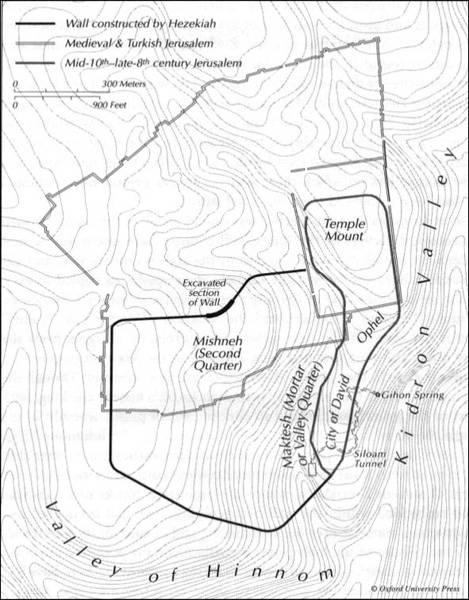

There are also indications that this period was one of rapid demographic growth in Judah. Archaeological surveys of the Judean hill country have uncovered several dozen new settlements founded toward the end of the eighth century

BCE

, and excavations in Jerusalem have shown that the capital’s developed area tripled or even quadrupled at the same time. Two of the city’s new neighborhoods are known by name, the Mishneh (“Second” Quarter) and the Maktesh (“Mortar” or “Valley” Quarter). Many if not most of the new settlers were probably refugees from the territories to the north and west that had been annexed to the Assyrian empire.

In religious affairs as well, Hezekiah took an active role as a reformer. Though the evidence is disputed, it seems that for the first time in Judah’s history the king, with the tacit support of the priesthood, set out to concentrate all public worship in the Jerusalem Temple. Local sanctuaries throughout the kingdom, the infamous “high places” that had served as the focal points of local ritual since earliest times, were shut down. An indication of what must have taken place at these sanctuaries was recovered by the excavators of ancient Beer-sheba, where the large stone blocks of a sacrificial altar were found embedded within the wall of a building; they had been used secondarily as construction material after the dismantling and desanctification of the altar. But whether the closure of the high places actually made the populace more dependent on the capital is questionable. Moreover, the king’s reform seems to have had another focus. His acts included the removal of ritual accoutrements that, though long associated with Israelite traditions, seemed to the authors of the reform essentially pagan. Stone pillars and Asherah-poles that had often been planted alongside the altars were eliminated, and even the

Nehushtan,

the venerated brazen serpent with a putative Mosaic pedigree that stood in the Jerusalem Temple, was removed from its honored position and smashed to pieces. All of these moves may have been inspired by a spirit of repentance urged by the reformers, who could point to the destruction of the northern kingdom as an object lesson: only by observing the demands of the Mosaic law for worship devoid of all images and concentrated at a single chosen site could Judah’s future be secured. These radical changes did not meet with universal approval, and with Hezekiah’s passing the status quo ante returned.

Not to be overlooked in all this activism is the literary output that flowed under royal sponsorship. Wisdom teachers had had entree to the Jerusalem court from its earliest days, and now at Hezekiah’s direction this circle set about copying and collecting Solomonic sayings, thus preserving for later generations the image of Solomon as the wisest of men (see Prov. 25.1). Other literature, with roots in northern Israel,

made its way south with the Israelite refugees who fled the Assyrian wars in search of a new home in Judah. Among these were such works as the popular tales of the wonder-working prophets Elijah and Elisha, collections of the sayings of prophets such as Hosea, and the nucleus of the material that was to become the book of Deuteronomy. In Jerusalem these traditions were accommodated and eventually included in the canon of sacred scripture that grew up there. It may have been during these heady days of Hezekiah’s first decade of rule that there was composed an early version of the Deuteronomic History, the narrative history of Israel in the land that eventually comprised the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings.

Prophets of another kind were active in Judah in the last quarter of the eighth century, the most prominent being Isaiah son of Amoz. This proud Jerusalemite served as the occasional counselor of both King Ahaz and King Hezekiah, but his pronouncements were directed for the most part to Israel in its entirety, the “house of Jacob.” Like his contemporary Micah from the lowland town of Moresheth, he introduced Judeans to the kinds of teachings developed by Amos and Hosea, prophets who had been active in the northern kingdom prior to the fall of Samaria. A hallmark of these literary prophets—a more apt designation than the customary “classical prophets”—was their call for societal reform. A new kind of idolatry had taken root in Judah: the worship of material gains. Isaiah observed that a great rift had opened between Judah’s influential wealthy and the neglected populace, whose cause he took up:

Ah, you who join house to house,

who add field to field,

until there is room for no one but you….

Ah, you who call evil good and good evil…

who acquit the guilty for a bribe,

and deprive the innocent of their rights!…

Therefore the anger of the L

ORD

was kindled against his people.

(Isa. 5.8, 20, 23, 25)

The prophet decried the piety of the privileged who had been led to believe that correct ritual observance was all that was needed; in God’s name he rejected their pretense:

Trample my courts no more;

bringing offerings is futile. . . .

When you stretch out your hands,

I will hide my eyes from you;

even though you make many prayers,

I will not listen;

your hands are full of blood….

Cease to do evil,

learn to do good;

seek justice,

rescue the oppressed,

defend the orphan,

plead for the widow.

(Isa. 1.12–17)

Micah put it succinctly:

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the L

ORD

require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God?

(Mic. 6.8)

Sacrifice could no longer guarantee the common weal. The new prophetic standard for national well-being elevated morality to the level previously occupied by ritual obligations alone; the responsibility of the individual to pursue justice as taught in the Mosaic law was extended to the entire nation, henceforth seen as collectively accountable for the ills of society.

Isaiah’s message also had a universal aspect. In his vision of a new world in days to come, all nations would make pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. There, in this house of instruction, they would be taught the ways of the Lord, thus ushering in an age of universal peace:

They shall beat their swords into plowshares,

and their spears into pruning hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more.

(Isa. 2.4)

For the present, Assyria’s victories were prophetically interpreted as God-sent punishments for the godless. But that rod of the Lord’s anger would in turn be punished for its shameless pride and boasting self-acclaim. In his mind’s eye, Isaiah foresaw a time when the Assyrian empire would be united in the worship of the one God:

On that day there will be a highway from Egypt to Assyria, and the Assyrian will come into Egypt, and the Egyptian into Assyria, and the Egyptians will worship with the Assyrians. On that day Israel will be the third with Egypt and Assyria, a blessing in the midst of the earth, whom the L

ORD

of hosts has blessed, saying, “Blessed be Egypt my people, and Assyria the work of my hands, and Israel my heritage.” (Isa. 19.23–25)

Because of their unorthodox message, more than once these visionaries found themselves confronting a hostile audience. Amos was banished from Bethel by its high priest, who branded as sedition his prophecy of the impending punishment of Israel’s leaders (Amos 7.10–12). On the other hand, Isaiah seems to have remained a keen social critic of his compatriots for over three decades, continually calling Judah’s ruling classes into line. Micah too fared well; Hezekiah was won over by the prophet’s somber prediction of Jerusalem’s destruction. A century later, when the mob threatened Jeremiah for his message of doom, some people still remembered the similar words of Micah and their positive effect on Hezekiah (Jer. 26.1–19).

Throughout most of Hezekiah’s reign, tensions remained high between Assyria and the states along the Mediterranean. Sargon continued to consolidate his hold. The Assyrian presence on the coast, as far as the border of Sinai, was reinforced by

resettling foreign captives in an emporium in which Assyrians and Egyptians “would trade together” (Sargon prism inscription from Nimrud, col. 4,11.46–50), a remarkable free-market policy for its time. Even the nomads of the desert, who were major players in the movement of overland trade, were integrated within the imperial administration.

Yet significant as these developments may have been, they did not bring stability; rebellion, an ever-ready option, broke out whenever the Assyrian overlord seemed inattentive or weak. In 713 Sargon replaced Azur, the upstart ruler of Ashdod (an important Philistine city on the southwest coast of the Mediterranean), with his brother, an Assyrian loyalist. He in turn was ousted by Yamani, who sought to lure other vassal kingdoms in the southern region, among them Judah, to his side. At about this time, emissaries of Merodach-baladan (the biblical rendering of Mardukapal-iddina), the Chaldean king of Babylonia, arrived in Jerusalem; ostensibly, they had come on a courtesy visit to inquire of Hezekiah’s health, which had recently been failing. Merodach-baladan was a known foe of Assyria with a record of rebellion, and conceivably while in Jerusalem his envoys discussed diplomatic and perhaps even economic relations between Judah and Babylonia. Sargon himself did not lead the army that came to restore order in Ashdod; rather, it was his army commander who in 712 attacked and captured Ashdod as well as several neighboring Philistine towns, carrying off rich spoil and numerous prisoners. Ashdod was reorganized as an Assyrian province, a first for the region. There is reason to believe that Azekah, a town on the border of the Shephelah of Judah, was also attacked; a fragmentary Assyrian report describes the storming of this well-positioned fortress. Whatever the details, Hezekiah survived this blow and somehow avoided more serious Assyrian reprisals. He had to bide his time as a humbled vassal a bit longer before he would try again to free his kingdom.