The Oxford History of World Cinema (10 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

moment of the distinction between documentary and fiction film-making, given that the

Lumières for the most part filmed 'real' events and Mélièlis staged events. But such

distinctions were not a part of contemporary discourse, since many pre-1907 films mixed

what we would today call 'documentary' material, that is, events or objects existing

independently of the film-maker, with 'fictional' material, that is, events or objects

specifically fabricated for the camera. Take, for example, one of the rare multi-shot films

of the period, The Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison ( Edison,

1901), a compilation of four self-contained individual shots dealing with the execution of

the assassin of President William McKinley. The first two shots are panoramas of the

exterior of the prison, the third shows an actor portraying the condemned man in his cell,

and the fourth re-enacts his electrocution. Given films of this kind, it is more useful to

discuss very early genres in terms of similarities of subject-matters rather than in terms of

an imposed distinction between fiction and documentary.

Many turn-of-the-century films reflected the period's fascination with travel and

transportation. The train film, established by the Lumières, practically became a genre of

its own. Each studio released a version, sometimes shooting a moving train from a

stationary camera and sometimes positioning a camera on the front of or inside the train

to produce a travelling shot, since the illusion of moving through space seemed to thrill

early audiences. The train genre related to the travelogue, films featuring scenes both

exotic and familiar, and replicating in motion the immensely popular postcards and

stereographs of the period. Public events, such as parades, world's fairs, and funerals, also

provided copious material for early cameramen. Both the travelogue and the public event

film consisted of self-contained, individual shots, but producers did offer combinations of

these films for sale together with suggestions for their projection order, so that, for

example, an exhibitor could project several discrete shots of the same event, and so give

his audience a fuller and more varied picture of it. Early film-makers also replicated

popular amusements, such as vaudeville acts and boxing matches, that could be relatively

easily reenacted for the camera. The first Kinetoscope films in 1894 featured vaudeville

performers, including contortionists, performing animals, and dancers, as well as scenes

from Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. Again, the shots functioned as self-contained units

and were marketed as such, but exhibitors had the option of putting them together to form

an evening's entertainment. By 1897 the popular filmed boxing matches could potentially

run for an hour. The same was true of another of the most popular of early genres, Passion

plays telling the life of Christ, which were often filmed recordings of theatrical

companies' performances. A compilation of shots of the play's key events could last well

over an hour. A third group of films told one-shot mini-narratives, most often of a

humorous nature. Some were gag films, resembling the Lumières' Watering the Gardener,

in which the comic action takes place in the pro-filmic event, as for instance in Elopement

by Horseback ( Edison, 1891), where a young man seeking to elope with his sweetheart

engages in a wrestling match with the girl's father. Others relied for their humour upon

trick effects such as stop action, superimposition, and reverse action. The most famous are

the Mélièlis films, but this form was also seen in some of the early films made by Porter

for the Edison Company and by the film-makers of the English Brighton school. These

films became increasingly complicated, sometimes involving more than one shot. In

Williamson's film The Big Swallow ( 1901), the first shot shows a photographer about to

take a picture of a passer-by. The second shot replicates the photographer's viewpoint

through the camera lens, and shows the passerby's head growing bigger and bigger as he

approaches the camera. The man's mouth opens and the film cuts to a shot of the

photographer and his camera falling into a black void. The film ends with a shot of the

passer-by walking away munching contentedly.

1902/3-1907

In this period, the multi-shot film emerged as the norm rather than the exception, with

films no longer treating the individual shot as a self-contained unit of meaning but linking

one shot to another. However, film-makers may have been using a succession of shots to

capture and emphasize the highpoints of the action rather than construct either a linear

narrative causality or clearly establish temporal-spatial relations. As befits the 'cinema of

attractions', the editing was intended to enhance visual pleasure rather than to refine

narrative developments.

One of the strangest editing devices used in this period was overlapping action, which

resulted from film-makers' desire both to preserve the pro-filmic space and to emphasize

the important action by essentially showing it twice. Georges Mélièli's A Trip to the

Moon, perhaps the most famous film of 1902, covers the landing of a space capsule on

the moon in two shots. In the first, taken from 'space', the capsule hits the man in the

moon in the eye, and his expression changes from a grin to a grimace. In the second shot,

taken from the 'moon's surface', the capsule once again lands. These two shots, which

show the same event twice, can disconcert a modern viewer. This repetition of action

around a cut can be seen in an American film of the same year, How They Do Things on

the Bowery, directed by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company. An irate

waiter ejects a customer unable to pay his bill. In an interior shot the waiter throws the

man out and hurls his suitcase after him. In the following exterior shot, the customer

emerges from the restaurant followed closely by his suitcase. In a 1904 Biograph film The

Widow and the Only Man, overlapping action is used not to cover interior and exterior

events but to show the same event a second time in closer scale. In the first shot a woman

accepts her suitor's flowers and smells them appreciatively. Then, rather than a'match cut',

in which the action picks up at the beginning of the second shot from where it left off at

the end of the first, as would be dictated by present-day conventions, a closer shot shows

her repeating precisely the same action.

While overlapping action was a common means of linking shots, film-makers during this

period also experimented with other methods of establishing spatial and temporal

relations. One sees an instance of this in Trip to the Moon: having landed on the moon,

the intrepid French explorers encounter unfriendly extraterrestrials (who remarkably

resemble those 'hostile natives' the French were encountering in their colonies at this very

time!). The explorers flee to their spaceship and hurry back to the safety of Earth, their

descent covered in four shots and twenty seconds of film time. In the first shot, the

capsule leaves the moon, exiting at the bottom of the frame. In the second shot, the

capsule moves from the top of the frame to the bottom of the frame. In the third the

capsule moves from the top of the frame to the water, and in the fourth the capsule moves

from the water's surface to the sea-bed. This sequence is filmed much as it might be today,

with the movement of the spaceship following the convention of directional continuity,

that is, an object or a character should appear to continue moving in the same direction

from shot to shot, the consistent movement serving to establish the spatial and temporal

relationships between individual shots. But while a modern film-maker would cut directly

from shot to shot, Mélièlis dissolved from shot to shot, a transitional device that now

implies a temporal ellipsis. In this regard, then, the sequence can still be confusing for a

modern viewer.

Linking shots through dissolves was not in fact unusual in this period, and one can see

another example in Alice in Wonderland ( Hepworth, 1903). However, another English

film-maker, James Williamson, a member of the Brighton school, made two films in

1901, Stop Thief! and Fire!, in which direct cuts continue the action from shot to shot.

Stop Thief! shows a crowd chasing a tramp who has stolen a joint from a butcher,

motivating connections by the diagonal movement of characters through each of the

individual shots; the thief and then his pursuers entering the frame at the back and exiting

the frame past the camera. The fact that the camera remains with the scene until the last

character has exited reveals how character movement motivates the editing. Film-makers

found this editing device so effective that an entire genre of chase films arose, such as

Personal ( Biograph, 1904), in which would-be brides pursue a wealthy Frenchman. Many

films also incorporated a chase into their narratives, as did the famous 'first' Western The

Great Train Robbery ( Edison, 1903), in which the posse pursues the bandits for several

shots in the fllm's second half.

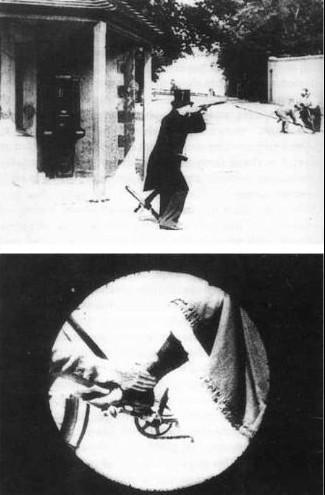

Early editing: two adjacent shots from G. A. Smith's As Seen through a Telescope ( 1900). The view through the telescope (achieved

by using a mask) shows a girl's ankle being stroked, thereby 'explaining' the previous shot

In Fire!, Williamson uses a similar editing strategy to that employed in Stop Thief!, the

movement of a policeman between shots 1 and 2 and the movement of fire engines

between shots 2 and 3 establishing spatial-temporal relations. But in the film's fourth and

fifth shots, where other film-makers might have used overlapping action, Williamson

experiments with a cut on movement that bears a strong resemblance to what is now

called a match cut. Shot 4, an interior, shows a fireman coming through the window of a

room in a burning house and rescuing the inhabitant. Shot 5 is an exterior of the burning

house and begins as the fireman and the rescued victim emerge through the window.

Although the continuity is 'imperfect' from a modern perspective, the innovation is

considerable. In his 1902 film Life of An American Fireman, undoubtedly influenced by

Fire!, Porter still employed overlapping action, showing a similar rescue in its entirety

first from the interior and then from the exterior perspective. A year later, however,

Williamson's compatriot G. A. Smith also created an 'imperfect' match cut, The Sick

Kitten ( 1903), cutting from a long view of two children giving a kitten medicine to a

closer view of the kitten licking the spoon.

During this period, film-makers also experimented with cinematically fracturing the space

of the pro-filmic event, primarily to enhance the viewers' visual pleasure through a closer

shot of the action rather than to emphasize details necessary for narrative comprehension.

The Great Train Robbery includes a medium shot of the outlaw leader, Barnes, firing his

revolver directly at the camera, which in modern prints usually concludes the film. The

Edison catalogue, however, informed exhibitors that the shot could come at the beginning

or the end of the film. Narratively non-specific shots of this nature became quite common,

as in the British film Raid on a Coiner's Den ( Alfred Collins , 1904), which begins with a

close-up insert of three hands coming into the frame from different directions, one

holding a pistol, another a pair of handcuffs, and a third forming a clenched fist. In

Porter's own oneshot film Photographing a Female Crook, a moving camera produces the

closer view as it dollies into a woman contorting her face to prevent the police from

taking an accurate mug shot.

Even shots that approximate the point of view of a character within the fiction, and which

are now associated with the externalization of thoughts and emotions, were then there

more to provide visual pleasure than narrative information. In yet another example of the

innovative film-making of the Brighton school, Grandma's Reading Glasses ( G. A.

Smith, Warwick Trading Company, 1900), a little boy looks through his grandmother's

spectacles at a variety of objects, a watch, a canary, and a kitten, which the film shows in

inserted close-ups. In The Gay Shoe Clerk ( Edison/ Porter, 1903) a shoeshop assistant