The Oxford History of World Cinema (32 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

alcoholism impaired his ability.

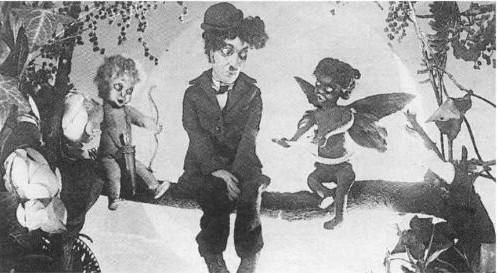

The Felix of this early period was drawn in an angular style and moved in jerky motions

rather like the walk of Chaplin's Tramp character. He was distinguished by a strong

personality which remained consistent from film to film; audiences could identify with

him and would return to see his next cartoon. Animator Bill Nolan, from 1922 to 1924,

redesigned Felix's body to make him more rounded and cuddly -- more like the Felix

dolls that Sullivan so successfully marketed.

The Sullivan studio was based on BarrÉ's model (Sullivan had worked at BarrÉ's briefly;

many of the animators came from there; BarrÉ himself worked on Felix from 1926 to

1928). Though cels were employed, they were background overlays, placed over sheets of

animated drawings on paper. This saved both the expense of cels and Bray-Hurd

licensing. Variations of the slash system were also used sporadically.

Felix the Cat in Pedigreedy ( 1927) by Pat Sullivan, directed by Otto Messmer . Character © Felix the Cat Productions,

Inc.

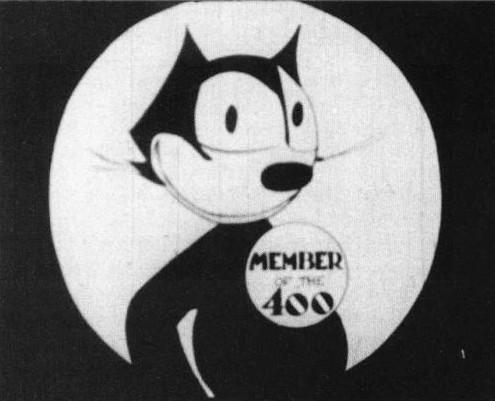

Felix became the first animated character to gain the attention of the cultural élite, as well

as huge popularity with audiences. He was the subject of praise from Gilbert Seldes, an

American cultural historian, from Marcel Brion, a member of the French Academy, and

from other intellectuals; Paul Hindemith composed a score for a 1928 Felix film. Thanks

to Sullivan's aggressive marketing, the character also became the most successful movie

'ancillary' (until knocked aside by Mickey). Felix's likeness was licensed for all kinds of

consumer products.

In 1925 Sullivan arranged to distribute through the Educational Film Corporation. Its

national network combined with the increasingly creative stories and superb

draughtsmanship of the Felix studio to generate the richest period, both in picture quality

and in revenue. The Felix craze became a world-wide phenomenon.

But the cat's bubble burst at its height of popularity. The demise of the series can be traced

to several factors: the coming of sound, competition from Mickey Mouse, and Sullivan's

draining the organization of its capital (while Disney was channelling every cent back in).

Despite the excellence of such films as Sure-Locked Homes ( 1928), Educational did not

renew its contract and the series went steadily downhill.

HARMAN, ISING, AND SCHLESINGER

When Mintz and Winkler took over Oswald the Rabbit in 1928, they hired Hugh Harman

and Rudolph Ising from Disney's studio to animate it. After Universal retrieved the series

and gave it to Walter Lantz, Harman and Ising formed a partnership and produced a pilot

film called Bosko the Talk-ink Kid in 1929. Entrepreneur Leon Schlesinger saw the

potential of tying in sound films with popular music and obtained backing from Warner

Bros. The film company would pay Schlesinger a fee to 'plug' its sheet music properties

by animating cartoons around the songs. In January 1930 the partnership began producing

'Looney Tunes' (then, in 1931, 'Merrie Melodies'), the kernel of what would become the

Warner Bros. cartoon studio with its memorable stars, beginning with Porky Pig.

ANIMATION IN OTHER NATIONAL CINEMAS

Every country with a significant silent film industry also had a local animation industry.

With the economic advantage gained during the 1914-18 war, the United States film

industry's financial impact on international cinema was reflected in the dissemination of

American cartoons. Cohl's 'Newlyweds' series, for example, was exported to France,

where it was distributed by the parent company, éclair. Chaplin's successful short films

were accompanied by US-made animated versions. BarrÉ's Edison films were distributed

by Gaumont. Margaret Winkler contracted with Pathé to distribute 'Out of the Inkwell'

and 'Felix the Cat' in Great Britain.

Despite foreign competition, there were two areas in which Europeans had the market to

themselves: topical sketches and advertising. The British sketchers, notably Harry

Furniss, Lancelot Speed, Dudley Buxton, George Studdy, and Anson Dyer, entertained

wartime audiences with their propaganda cartoons. Dyer went on to make some

successful short cartoons in the early 1920s, including Little Red Riding Hood ( 1922),

and would become an important producer in the 1930s. Studdy, in 1924, launched a series

of Bonzo films starring a chubby dog. Advertising was a familiar component of the film

programme. Among the notable names producing animated ads were O'Galop and Lortac

in France, Pinschewer, Fischinger, and Seeber in Germany. In a category by itself are the

productions of the State Film Technicum in Moscow. A regular series of entertainment

cartoons (with a social message) appeared from 1924 to 1927, supervised by Dziga

Vertov. The most important animator was Ivan Ivanov-Vano.

Other specialities were puppet and silhouette films. Ladislas Starewitch began his career

in Russia in 1910 and soon was releasing popular one-reel films with puppets and

animated insects for the Khanzhonkov Company. In 1922 he moved to France, where the

puppet film became his life's work.

Le Roman du renard

, completed in 1930, was the first

animated feature in France.

The important pioneer of the silhouette film was Lotte Reiniger. Her feature

Die

Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed

(

The Adventures of Prince Ahmed

) was released in Berlin

in 1926 and gained world-wide acclaim. Its Arabian Nights story, lively shadow-puppets,

and complicated moving backgrounds took three years to photograph.

Also worth mentioning are Quirino Cristiani and Victor Bergdahl. The former worked in

Argentina and released a political satire,

El apóstol

('The apostle'), in 1917. About an hour

in length (about the same as

Prince Achmed

), it has been called the first feature-length

cartoon. Bergdahl, from 1916 to 1922, animated a Swedish series featuring Kapten Grogg

which was distributed in Europe and in the United States.

As Giannalberto Bendazzi ( 1994) has documented, animation was practised in many

countries throughout the 1920s, both by avant-garde artists and commercially. But despite

the popularity of animation films, the economic realities of the film industry in the 1920s,

and the great cultural diversity in popular graphic humour traditions, made it extremely

difficult for other countries to compete on the world market with the output of the

American studios.

Bibliography

Bendazzi, Giannalberto ( 1994),

Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation

.

Cabarga, Leslie ( 1988),

The Fleischer Story

.

Canernaker, John ( 1987),

Winsor McCay: His Life and Art

.

------ ( 1991),

Felix: The Twisted Tale of the World's Most Famous Cat

.

Cholodenko, Alan (ed.) ( 1991),

The Illusion of Life: Essays on Animation

.

Crafton, Donald ( 1990),

Émile Cohl, Caricature and Film

.

------ ( 1993),

Before Mickey: The Animated Film, 1898-1928

.

Gifford, Denis ( 1987),

British Animated Films, 1895-1985: A Filmography

.

------ ( 1990),

American Animated Films: The Silent Era, 1897-1929

.

Maltin, Leonard ( 1980),

Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons

.

Merritt, Russell, and Kaufman, J. B. ( 1994),

Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of

Walt Disney

.

Robinson, David ( 1991),

'Masterpieces of Animation, 1833-1908'

.

Solomon, Charles ( 1987),

Enchanted Drawings: The History of Animation

.

Ladislas Starewitch (Władysław Starewicz) (1882-1965)

Władisław Starewicz was born in Vilnius -- now the capital of Lithuania but then part of

Poland -- and started his film career making documentaries for the local Ethnographic

Museum. His first animated film was

Valka zukov rogachi

('The Battle of Stag-Beetles',

1910), a reconstruction (using preserved specimens) of the nocturnal mating rituals of this

local species, which could not be filmed 'live-action' in the dark.For his first

entertainment film,

Prekrasnya Lukanida

(The fair Lucanida', 1910), Starewitch

developed the basic technique he would employ for the rest of his life: he built small

puppets from a jointed wooden frame, with parts such as fingers that needed to be flexible

rendered in wire, and parts that need not change cut from cork or modelled in plaster. His

wife Anna, who came from a family of tailors, padded them with cotton and sewed leather

and cloth features and costumes. He designed all the characters and built the settings.

Starewicz moved to Moscow, making animations which range from the impressively grim

The Grasshopper and the Ant (

Strekozai I muraviei,

1911) in which the literalness of the

insects reinforces the cruel message, to the enchanting The Insects' Christmas

(

Rozhdyestvo obitateli lyesa,

( 1912). His most astonishing early film, The Cameraman's

Revenge (

Miest kinooperatora,

1911), shows Mrs Beetle having an affair with a

grasshopper-painter, while Mr Beetle carries on with a dragonfly cabaret-artiste, whose

previous lover, a grasshopper-cameraman, shoots movies of Mr Beetle and Dragonfly

making love at the Hotel d'Amour. The cameraman screens these at the local cinema

when Mr and Mrs Beetle are present, and the resulting riot lands both Beetles in jail. This

racy satire of human sexual foibles gains a biting edge from the ridiculousness of bugs

enacting what humans consider their most serious (even tragic) passions -- as when Mrs

Beetle reclines like an odalisque on the divan awaiting the absurd embrace of her lover,

which involves twelve legs and two antennae in lascivious motion. The reflexive

representation of the cinematic apparatus, reaching its apotheosis in the projection of

previous scenes before an audience of animated insects, adds a metaphysical dimension to

the parable.After the Revolution, Starewicz left Russia and settled in France in 1920,

changing his name to Ladislas Starewitch. Here he made 24 films which combine witty

sophistication and magical naïveté, including moral fables such as the splendid The Town

Rat and the Country Rat (

Le Rat de ville et le Rat des champs,

1926) or the lovely

La voix

du rossignol

('The nightingale's voice', 1923), adventure epics like The Magic Clock

(

L'Horloge magique,

1928), a bitter rendering of Anderson's The Steadfast Tin Soldier

(

La Petite Parade,

1928), and a feature-length Reynard the Fox (

Le Roman de Renard,

shot 1929/30, released 1937) which renders the gestures and emotions of the animals (in

sophisticated period costumes) with great subtlety.His 1933 masterpiece The Mascot

(

Fétiche mascotte

) begins with a live-action sequence starring the Starewitch daughters

Irène and Jeanne (who assisted and acted in most of the films) as a mother who supports

herself making toys, and her sick daughter who longs for an orange. A stuffed dog,

Fétiche, sneaks out at night to steal an orange for the girl, but gets caught at the Devil's

ball, where all the garbage of Paris comes to life in a dissolute orgy at which drunken

stemware suicidally crash into each other, and re-assembled skeletons of eaten fish and

chikens dance. The dog escapes with the orange, pursued home by a motley gang of torn-

paper and vegetable people, dolls and animals. Starewitch nods homage to René Clair's

Dada short Entr'acte in his use of speeding live-action street traffic, the saxophone player

with a balloon head that inflates and deflates as he plays, and the climactic mad, weird

pursuit. Starewitch matches his brilliant visual details with witty use of sound, making the

voices of Fètiche and the Devil whining musical instruments, or playing the Devil's words

backwards to sound like unearthly gibberish.