The Oxford History of World Cinema (42 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

films, which broadly set up a different space for viewing from narrative drama, in which

stable perception is interrupted and non-identification of subject and image are aimed for.

Chien andalou

sets up another model, in which elements of narrative and acting arouse

the spectator's psychological participation in plot or scene while at the same time

distancing the viewer by disallowing empathy, meaning, and closure; an image of the

dissociated sensibility or 'double consciousness' praised by Surrealism in its critique of

naturalism.

Two further French films expand this strategy, which came with the sound film era and

the end of the first phase of avant-garde film-making before the rise of Hitler;

L'Age d'or

('The golden age', 1930) and Blood of a Poet ( 1932). Almost feature length, these films

(privately funded by arts patron the Vicomte de Noailles as successive birthday presents

to his wife) link Cocteau's lucid classicism to Surrealism's baroque mythopoeia. Both

films ironize visual meaning in voice-over or by intertitles (made on the cusp of the sound

era, they use both spoken and written text). Cocteau's voice raspingly satirizes his Poet's

obsession with fame and death ('Those who smash statues should beware of becoming

one'), paralleled in the opening of

L'Age d'or

by an intertitle 'lecture' on scorpions and an

attack on Ancient and modern Rome. Bufiuel links the fall of the classical age to his main

target, Christianity (as when Christ and the disciples are seen leaving a chateau after a

Sadean orgy). The film itself celebrates 'mad love'. A text written by the surrealists and

signed by Aragon, Breton, Dalí, Éluard, Peret, Tzara and others was issued at the first

screening:

L'Age d'or

, 'uncorrupted by plausibility', reveals the 'bankruptcy of our

emotions, linked with the problem of capitalism'. The manifesto echoes Vigo's

endorsement of

Un chien andalou's

'savage poetry' (also in 1930) as a film of 'social

consciousness'. 'An Andalusian dog howls,' wrote Vigo; 'who then is dead?'

Unlike Buñuel's film, Cocteau's is not overtly anti-theocratic, but even so his Poet-hero

encounters archaic art, magic and ritual, China, opium, and transvestism before dying in

front of an indifferent stage audience while he plays cards. Cocteau's film finally affirms

the redemptive classic tradition, but the dissolution of personal identity opposes the

western fixation on stability and repetition, asserting that any modern classicism was to

be determinedly 'neo'.

THE 1930s

Experimental sound-tracks and minimal synchronized speech in these films expanded the

call for a non-naturalistic sound cinema in Eisenstein's and Pudovkin's 1928 manifesto

and explored by Vertov's Enthusiasm ( 1930). This direction was soon blocked by the

popularity and realism of the commercial sound film. Rising costs of film-making and the

limited circulation of avant-garde films contributed to their decline. The broadly leftist

politics of the avant-garde -- both surrealists and abstract constructivists had complex

links to Communist and socialist organizations-were increasingly strained under two

reciprocal policies which dominated the 1930s; the growth of German nationalism under

Hitler from 1933 and the Popular Front opposition to Fascism which rose, under

Moscow's lead, a few years later. The attack on 'excessive' art and the avant-garde in

favour of popular 'realism' were soon to close down the international co-operation which

made possible German-Soviet co-productions like Piscator's formally experimental

montage film Revolt of the Fishermen ( 1935) or Richter's first feature film Metall

(abandoned in 1933 after the Nazi take-over). Radical Soviet film-makers as well as their

'cosmopolitan' allies abroad were forced into more normative directions.

The more politicized film-makers recognized this themselves in the second international

avant-garde conference held in Belgium in 1930. The first more famous congress in 1929

at La Sarraz, Switzerland, at which Eisenstein, Balàzs, Moussinac, Montagu, Cavalcanti,

Richter, and Ruttmann were present, had endorsed the need for aesthetic and formal

experiment as part of a still growing movement to turn 'enemies of the film today' into

'friends of the film tomorrow', as Richter's optimistic 1929 book affirmed. One year later

the stress was put emphatically on political activism, Richter's social imperative: 'The age

demands the documented fact,' he claimed.

The first result of this was to shift avant-garde activity more directly into documentary.

This genre, associated with political and social values, still encouraged experiment and

was ripe for development of sound and image montage to construct new meanings. In

addition, the documentary did not use actors; the final barrier between the avant-garde

and mainstream or art-house cinema.

The documentary -- usually used to expose social ills and (via state or corporate funding)

propose remedies -attracted many European experimental film-makers including Richter,

Ivens, and Henri Storck. In the United States, where there was a small but volatile

community of activists for the new film, alongside other modern developments in writing,

painting, and photography, the cause of a radical avant-garde was taken up by magazines

such as

Experimental Film

and seeped into the New Deal films made by Pare Lorentz and

Paul Strand (a modernist photographer since the age of Camerawork and New York

Dada).

In Europe, notably with John Grierson, Henri Storck, and Joris Ivens, new fusions

between experimental film and factual cinema were pioneered. Grierson's attempt to

equate corporate patronage with creative production led him most famously to the GPO,

celebrated as an emblem of modern social communications in the Auden -- Britten

montage section of

Night Mail

( 1936), which ends with Grierson's voice intoning a night-

time hymn to Glasgow -'let them dream their dreams . . .'.

Alberto Cavalcanti and Len Lye were hired to open the documentary cinema to new ideas

and techniques. Lye's uncompromising career as a film-maker, almost always for state and

business patrons, showed the survival of sponsored funding for the arts in Europe and the

USA in the depression years. His cheap and cheerfully hand-made colour-experiments of

the period treat their overt subjects (parcel deliveries in the wholly abstract A Colour Box

( 1935), early posting in Trade Tattoo ( 1937) with a light touch; the films celebrate the

pleasures of pure colour and rhythmic sound-picture montage. The loss of both Grierson

and Lye to North America after the 1940s marked the end of this period of collaboration.

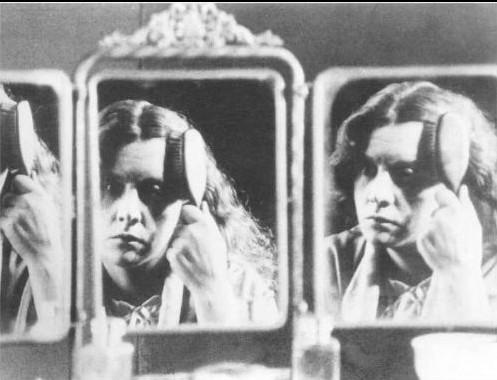

Germaine Dermoz as the bored wife in Germaine Dulac 's

Smiling Madame Beudet

(

La Souriante Madame Beudet

, 1923)

HARMONY AND DISRUPTION

The now legendary conflict between director Germaine Dulac and poet Antonin Artaud,

over the making of The Seashell and the Clergyman (

La Coquille et le clergyman

, 1927)

from his screenplay, focuses some key issues in avantgarde film. Dulac made both

abstract films such as

Étude cinÉgraphique sur une arabesque

('Cinematic study of a

flourish', 1923) and stylish narratives, of which the best known is the pioneering feminist

work Smiling Madame Beudet (

La Souriante Madame Beudet

, 1923). These aspects of

her work were linked by a theory of musical form, to 'express feelings through rhythms

and suggestive harmonies'. But Artaud opposed this vehemently, along with

representation itself. In his 'Theatre of Cruelty', Artaud foresaw the tearing down of

barriers between public and stage, act and emotion, actor and mask. In film, he wrote in

1927, he wanted 'pure images' whose meanings would emerge, free of verbal associations,

'from the very impact of the images themselves'. The impact must be violent, 'a shock

designed for the eyes, a shock founded, so to speak, on the very substance of the gaze'.

For Dulac too, film is 'impact', but typically its effect is 'ephemeral . . . analogous to that

provoked by musical harmonies'. Dulac fluently explored film as dream state (expressed

in the dissolving superimpositions in La Coquille) and so heralded the psychodrama film,

but Artaud wanted film only to keep the dream state's most violent and shattering

qualities, breaking the trance of vision.

Here, the avant-garde focused on the role of the spectator. In the abstract film, analogies

were sought with nonnarrative arts to challenge cinema as a dramatic form, and this led to

'visual music' or 'painting in motion'. In Jean Coudal's 1925 surrealist account, film

viewing is seen as akin to 'conscious hallucination', in which the body -undergoing

'temporary depersonalization' -- is robbed of 'its sense of its own existence. We are

nothing more than two eyes rivetted to ten meters of white screen, with a fixed and guided

gaze.' This critique was taken further in Dalí's "Abstract of a Critical History of the

Cinema" ( 1932), which argues that film's 'sensory base' in 'rhythmic impression' leads it

to the

bête noire

of harmony, defined as 'the refined product of abstraction', or

idealization, rooted in 'the rapid and continuous succession of film images, whose implicit

neologism is directly proportional to a specifically generalizing visual culture'.

Countermanding this, Dalí looks for 'the poetry of cinema' in 'a traumatic and violent

disequilibrium veering towards concrete irrationality'.

The goal of radical discontinuity did not stop short at the visual image, variously seen as

optical and illusory (by Bufiuel) or as retinal and illusionist (by Duchamp). The linguistic

codes in film (written or spoken) were also scoured, as in films by Man Ray, Buñuel, and

Duchamp which all play with intertitles to open a gap between word, sign, and object.

The attack on naturalism continued into the sound era, notably in Buñuel's documentary

on the Spanish poor,

Las Hurdes

(

Land without Bread

, 1932). Here, the surrealist Pierre

Unik's commentary -- a seemingly authoritative 'voice-over' in the tradition of factual

filmslowly undermines the realism of the images, questioning the depiction (and viewing)

of its subjects by a chain of

non sequiturs

or by allusions to scenes which the crews -- we

are told -- failed, neglected, or refused to shoot. Lacunae open between voice, image, and

truth, just as the eye had been suddenly slashed in Un chien andalou.

Paradoxically, the assault on the eye (or on the visual order) can be traced back to the

'study of optics' which Cézanne had recommended to painters at the dawn of modernism.

This was characteristically refined by Walter Benjamin in 1936, linking mass

reproduction, the cinema, and art: 'By its transforming function, the camera introduces us

to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.'

The discontinuity principle underlies the avant-garde's key rhetorical figure, paratactic

montage, which breaks the flow -- or 'continuity' -- between shots and scenes, against the

grain of narrative editing. Defined by Richter as 'an interruption of the context in which it

is inserted', this form of montage first appeared in the avant-garde just as the mainstream

was perfecting its narrative codes. Its purpose is counter-narrative, by linking dissonant

images which resist habits of memory and perception to underline the film event as

phenomenological and immediate. At one extreme of parataxis, rapid cutting -down to the

single frame -- disrupts the forward flow of linear time (as in the 'dance' of abstract shapes

in Ballet mécanique). At the other extreme, the film is treated as raw strip, frameless and

ageless, to be photogrammed by Man Ray or hand-painted by Len Lye. Each option is a

variation spun from the kaleidoscope of the modernist visual arts.

This diversity -- reflected too in the search for noncommercial funding through patronage

and self-help cooperatives -- means that there is no single model of avantgarde film

practice, which has variously been seen to relate to the mainstream as poetry does to

prose, or music to drama, or painting to writing. None of these suggestive analogies is