The Paleo Diet for Athletes (26 page)

Read The Paleo Diet for Athletes Online

Authors: Loren Cordain,Joe Friel

Humans, unlike cats, still maintain the ability to synthesize taurine in the liver from precursor substances. However, this ability is limited and inefficient—so much so that infant formula must be supplemented with taurine. Without taurine supplementation in infant formula, bottle-fed babies are more susceptible to visual and hearing problems as they grow. Even adults don’t fare much better if they stop eating meat. Studies show that vegan vegetarians have low levels of blood and urinary taurine—levels that indicate our poor ability to synthesize taurine from vegetable amino acids. Similar to that of cats, our inefficiency to build

taurine from plant amino acids occurred because of our long reliance upon taurine-rich animal food.

A second example, similar to the taurine story, is the situation with long-chain fatty acids. Cats have almost completely lost the ability of the liver to convert 18-carbon to 20-carbon fatty acids. All cells in the bodies of mammals require 20-carbon fatty acids to make localized hormones called eicosanoids and prostaglandins. Herbivores have no choice but to synthesize 20-carbon fatty acids in their livers from plant-based 18-carbon fatty acids, since 20-carbon fatty acids occur only in animal food and are not found in any plant foods. Again, cats have nearly lost the ability to build 20-carbon fatty acids from their 18-carbon precursors because there was no need for it; they got all the preformed 20-carbon fatty acids they required from the flesh of their prey. Similarly, humans maintain very inefficient pathways to convert 18- to 20-carbon fatty acids because of our more than 2-million-year history of meat consumption.

In the Introduction, we discussed the foods that couldn’t have been consumed by our Stone Age ancestors; in this chapter, we illustrated those that were eaten. By putting both of these pieces of the puzzle together, we get a much clearer picture of the foods that we are genetically programmed to eat. These are the foods that provide us with optimal health and well-being. By mimicking the nutritional characteristics of the ancestral human diet with commonly available modern foods, it is entirely possible to eat a Stone Age diet in the 21st century. In the next chapter, we will explain how easily this can be accomplished.

CHAPTER 9

T

HE

21

ST

-C

ENTURY

P

ALEO

D

IET

SPECIAL DIETARY NEEDS OF MODERN ATHLETES

As a serious athlete, you have a lifestyle and an activity level that are far different from that of the average American. Chances are your training patterns also vary significantly from the daily activity patterns of our Paleolithic ancestors. They were unlikely to ever run 26.2 miles as fast as they could, nonstop. Nor would they work and run at high-intensity levels day after day, week after week. The only reason they would have done so would have been under extreme conditions in which their lives were continually at risk, and the only way to survive was to run far and fast every day. Such situations were rare. As you will see in the next chapter, the more typical manner of “exercise” for the Paleolithic athlete would have involved long, steady hunts and foraging expeditions conducted at a moderate pace until the kill was imminent or the gathered foods were hauled back to camp. At these times their effort would increase, but they would no doubt rest at every opportunity. Ceremonial dance would also provide nearly continuous “exercise,” but the intensity would be relatively low.

What all of this means for you is that your diet must be modified slightly to accommodate your “unusual” high-level training patterns that are a requisite for peak performance during competition. These

modifications, as you are now well aware, involve exactly when and what you eat before, during, and immediately following exercise. These critical dietary nuances were discussed extensively in

Chapters 2

,

3

, and

4

.

Now let’s get down to the crux of this chapter: What should you eat for the remainder of your day, from the time short-term recovery ends until just before the next workout begins? During this period, you should be eating in a manner similar to that of your Paleolithic ancestors. You’ll quickly discover that your day-to-day recovery is greatly enhanced and, as a result, your performance will improve.

21ST-CENTURY DIETARY TWEAKS

Let’s make it clear from the start: It would be nearly impossible for any athlete or fitness enthusiast living in a typical modern setting to exactly replicate a Paleolithic hunter-gatherer diet. Many of those foods are unavailable commercially, no longer exist, or are totally disgusting to modern tastes and cultural traditions. Do brains, marrow, tongue, and liver sound appealing to you? Probably not, but to hunter-gatherers, these organs were mouthwatering treats that were gobbled up every time an animal was killed. For hunter-gatherers, the least appetizing part of the carcass was the muscle tissue, which is about the only meat most of us ever eat.

Produce for the Paleo Athlete

Most of the familiar fruits and veggies that we find in the produce section of our supermarkets bear little resemblance to their wild counterparts. Large, succulent, orange carrots of today were nothing more than tiny purple or black fibrous roots 1,000 years ago. The numerous varieties of juicy, sweet apples that we enjoy would have resembled tiny, bitter crab apples a few thousand years ago. Thanks to thousands of years of selective breeding, irrigation, and, later, fertilizers and pesticides, we now eat domesticated fruits and veggies that are larger and sweeter and have less fiber and more carbohydrate than their wild versions.

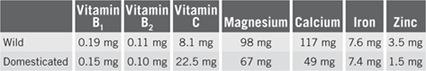

Figure 9.1

contrasts the fiber content of wild and cultivated plants in a 100-gram sample, and

Table 9.1

compares the vitamin and mineral content of wild plant foods and their domesticated counterparts. You can see that the B vitamins, iron, and zinc concentrations are comparable between the two, whereas wild plants have more calcium and magnesium, and domesticated plants are better sources of vitamin C. Unless you are fortunate enough to live where you can harvest Mother Nature’s nuts, berries, or other uncultivated plant foods, most of us will rarely eat wild plant foods on a regular basis. Nevertheless, it matters little because the overall nutritional differences between wild and domesticated plants are small and generally insignificant.

FIGURE 9.1

TABLE 9.1

Comparison of the Vitamin and Mineral Content of Wild and Domesticated Plants

Fresh produce is an essential element of contemporary Paleo diets, and I encourage you to eat as much of these healthy foods as you possibly can. The only excluded vegetables are potatoes, cassava root, sweet corn, and legumes (peas, green beans, kidney beans, pinto beans, peanuts, etc.). Fruits are Mother Nature’s natural sweets, and the only fruits you should totally steer clear of are canned fruits packed in syrups. Dried fruits should be consumed sparingly by most nonathletes, as they can contain as much concentrated sugar as candy does. Nevertheless, most trained endurance athletes can eat dried fruit with few adverse health consequences because athletes in general maintain sensitive insulin metabolisms. If you are obese or have one or more diseases of the metabolic syndrome (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, or abnormal blood lipids), you should sidestep dried fruit altogether and eat sparing amounts of the “very high” and “high” sugar fruits listed in

Table 9.2

. Once your weight returns to normal and disease symptoms fade away, eat as much fresh fruit as you please.

TABLE 9.2

Sugar Content in Dried and Fresh Fruits

| DRIED FRUITS | |

| Extremely high in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Dried mango | 73.0 |

| Raisins, golden | 70.6 |

| Zante currants | 70.6 |

| Raisins | 65.0 |

| Dates | 64.2 |

| Dried figs | 62.3 |

| Dried papaya | 53.5 |

| Dried pears | 49.0 |

| Dried peaches | 44.6 |

| Dried prunes | 44.0 |

| Dried apricots | 38.9 |

| FRESH FRUITS | |

| Very high in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Grapes | 18.1 |

| Banana | 15.6 |

| Mango | 14.8 |

| Cherries, sweet | 14.6 |

| High in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Apples | 13.3 |

| Pineapple | 11.9 |

| Purple passion fruit | 11.2 |

| Moderate in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Kiwifruit | 10.5 |

| Pear | 10.5 |

| Pear, Bosc | 10.5 |

| Pear, D’Anjou | 10.5 |

| Pomegranate | 10.1 |

| Raspberries | 9.5 |

| Apricots | 9.3 |

| Orange | 9.2 |

| Moderate in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Watermelon | 9.0 |

| Cantaloupe | 8.7 |

| Peach | 8.7 |

| Nectarine | 8.5 |

| Jackfruit | 8.4 |

| Honeydew melon | 8.2 |

| Blackberries | 8.1 |

| Cherries, sour | 8.1 |

| Tangerine | 7.7 |

| Plum | 7.5 |

| Low in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Blueberries | 7.3 |

| Star fruit | 7.1 |

| Elderberries | 7.0 |

| Figs | 6.9 |

| Mamey apple | 6.5 |

| Grapefruit, pink | 6.2 |

| Grapefruit, white | 6.2 |

| Guava | 6.0 |

| Guava, strawberry | 6.0 |

| Papaya | 5.9 |

| Strawberries | 5.8 |

| Casaba melon | 4.7 |

| Very low in total sugars | Total sugars per 100 grams |

| Tomato | 2.8 |

| Lemon | 2.5 |

| Avocado, California | 0.9 |

| Avocado, Florida | 0.9 |

| Lime | 0.4 |