The Panda’s Thumb (14 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

I believe that we must reassess fundamentally the relative importance we have assigned to upright posture and increase in brain size as determinants of human evolution. We have viewed upright posture as an easily accomplished, gradual trend and increase in brain size as a surprisingly rapid discontinuityâsomething special both in its evolutionary mode and the magnitude of its effect. I wish to suggest a diametrically opposite view. Upright posture is the surprise, the difficult event, the rapid and fundamental reconstruction of our anatomy. The subsequent enlargement of our brain is, in anatomical terms, a secondary epiphenomenon, an easy transformation embedded in a general pattern of human evolution.

Six million years ago at most, if the molecular clock runs true (and Wilson and Sarich would prefer five), we shared our last common ancestor with gorillas and chimps. Presumably, this creature walked primarily on all fours, although it may have moved about on two legs as well, as apes and many monkeys do today. Little more than a million years later, our ancestors were as bipedal as you or I. This, not later enlargement of the brain, was the great punctuation in human evolution.

Bipedalism is no easy accomplishment. It requires a fundamental reconstruction of our anatomy, particularly of the foot and pelvis. Moreover, it represents an anatomical reconstruction outside the general pattern of human evolution. As I argue in essay 9, through the agency of Mickey Mouse, humans are neotenicâwe have evolved by retaining juvenile features of our ancestors. Our large brains, small jaws, and a host of other features, ranging from distribution of bodily hair to ventral pointing of the vaginal canal, are consequences of eternal youth. But upright posture is a different phenomenon. It cannot be achieved by the “easy” route of retaining a feature already present in juvenile stages. For a baby's legs are relatively small and weak, while bipedal posture demands enlargement and strengthening of the legs.

By the time we became upright as

A. afarensis

, the game was largely over, the major alteration of architecture accomplished, the trigger of future change already set. The later enlargement of our brain was anatomically easy. We read our larger brain out of the program of our own growth, by prolonging rapid rates of fetal growth to later times and preserving, as adults, the characteristic proportions of a juvenile primate skull. And we evolved this brain in concert with a host of other neotenic features, all part of a general pattern.

Yet I must end by pulling back and avoiding a fallacy of reasoningâthe false equation between magnitude of effect and intensity of cause. As a pure problem in architectural reconstruction, upright posture is far-reaching and fundamental, an enlarged brain superficial and secondary. But the effect of our large brain has far outstripped the relative ease of its construction. Perhaps the most amazing thing of all is a general property of complex systems, our brain prominent among themâtheir capacity to translate merely quantitative changes in structure into wondrously different qualities of function.

It is now two in the morning and I'm finished. I think I'll walk over to the refrigerator and get a beer; then I'll go to sleep. Culture-bound creature that I am, the dream I will have in an hour or so when I'm supine astounds me ever so much more than the stroll I will now perform perpendicular to the floor.

GREAT STORYTELLERS OFTEN

insert bits of humor to relieve the pace of intense drama. Thus, the gravediggers of Hamlet or the courtiers Ping, Pong and Pang of Puccini's

Turandot

prepare us for torture and death to follow. Sometimes, however, episodes that now inspire smiles or laughter were not so designed; the passage of time has obliterated their context and invested the words themselves with an unintended humor in our altered world. Such a passage appears in the midst of geology's most celebrated and serious documentâCharles Lyell's

Principles of Geology

, published in three volumes between 1830 and 1833. In it, Lyell argues that the great beasts of yore will return to grace our earth anew:

Then might those genera of animals return, of which the memorials are preserved in the ancient rocks of our continents. The huge iguanodon might reappear in the woods, and the ichthyosaur in the sea, while the pterodactyl might flit again through the umbrageous groves of tree-ferns.

Lyell's choice of image is striking, but his argument is essential to the major theme of his great work. Lyell wrote the

Principles

to advance his concept of uniformity, his belief that the earth, after “settling down” from the effects of its initial formation, had stayed pretty much the sameâno global catastrophes, no steady progress towards any higher state. The extinction of dinosaurs seemed to pose a challenge to Lyell's uniformity. Had they not, after all, been replaced by superior mammals? And didn't this indicate that life's history had a direction? Lyell responded that the replacement of dinosaurs by mammals was part of a grand, recurring cycleâthe “great year”ânot a step up the ladder of perfection. Climates cycle and life matches climates. Thus, when the summer of the great year came round again, the cold-blooded reptiles would reappear to rule once more.

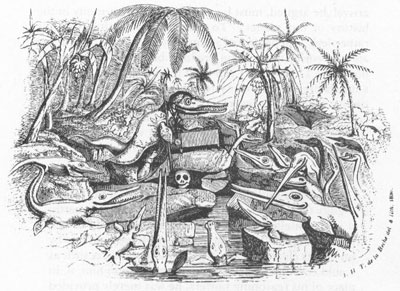

In a satirical cartoon drawn by one of Lyell's colleagues in response to the cited passage about returning ichthyosaurs and pterodactyls, the future Prof. Ichthyosaurus lectures to students on the skull of a strange creature of the last creation.

And yet, for all the fervor of his uniformitarian conviction, Lyell did allow one rather important exception to his vision of an earth marching resolutely in placeâthe origin of

Homo sapiens

at the latest instant of geological time. Our arrival, he argued, must be viewed as a discontinuity in the history of our planet: “To pretend that such a step, or rather leap, can be part of a regular series of changes in the animal world, is to strain analogy beyond all reasonable bounds.” To be sure, Lyell tried to soften the blow he had administered to his own system. He argued that the discontinuity reflected an event in the moral sphere aloneâan addition to another realm, not a disruption of the continuing steady-state of the purely material world. The human body, after all, could not be viewed as a Rolls Royce among mammals:

When it is said that the human race is of far higher dignity than were any pre-existing beings on the earth, it is the intellectual and moral attributes only of our race, not the animal, which are considered; and it is by no means clear, that the organization of man is such as would confer a decided pre-eminence upon him, if, in place of his reasoning powers, he was merely provided with such instincts as are possessed by the lower animals.

Nonetheless, Lyell's argument is a premier example of an all too common tendency among natural historiansâthe erection of a picket fence around their own species. The fence sports a sign: “so far, but no farther.” Again and again, we encounter sweeping visions, encompassing everything from the primordial dust cloud to the chimpanzee. Then, at the very threshold of a comprehensive system, traditional pride and prejudice intervene to secure an exceptional status for one peculiar primate. I discuss another example of the same failure in essay 4âAlfred Russel Wallace's argument for the special creation of human intelligence, the only imposition by divine power upon an organic world constructed entirely by natural selection. The specific form of the argument varies, but its intent is ever the sameâto separate man from nature. Below its main sign, Lyell's fence proclaims: “the moral order begins here” Wallace's reads: “natural selection no longer at work.”

Darwin, on the other hand, extended his revolution in thought consistently throughout the entire animal kingdom. Moreover, he explicitly advanced it into the most sensitive areas of human life. Evolution of the human body was upsetting enough, but at least it left the mind potentially inviolate. But Darwin went on. He wrote an entire book to assert that the most refined expressions of human emotion had an animal origin. And if feelings had evolved, could thoughts be far behind?

The picket fence around

Homo sapiens

rests on several supports; the most important posts embody claims for

preparation

and

transcendence

. Humans have not only transcended the ordinary forces of nature, but all that came before was, in some important sense, a preparation for our eventual appearance. Of these two arguments, I regard preparation as by far the more dubious and more expressive of enduring prejudices that we should strive to shed.

Transcendence, in modern guise, states that the history of our peculiar species has been directed by processes that had not operated before on earth. As I argue in essay 7, cultural evolution is our primary innovation. It works by the transmission of skills, knowledge and behavior through learningâa cultural inheritance of acquired characters. This nonbiological process operates in the rapid “Lamarckian” mode, while biological change must plod along by Darwinian steps, glacially slow in comparison. I do not regard this unleashing of Lamarckian processes as a transcendence in the usual sense of overcoming. Biological evolution is neither cancelled nor outmaneuvered. It continues as before and it constrains patterns of culture; but it is too slow to have much impact on the frenetic pace of our changing civilizations.

Preparation, on the other hand, is hubris of a much deeper kind. Transcendence does not compel us to view four billion years of antecedent history as any foreshadowing of our special skills. We may be here by unpredictable good fortune and still embody something new and powerful. But preparation leads us to trace the germ of our later arrival into all previous ages of an immensely long and complicated history. For a species that has been on earth for about 1/100, 000 of its existence (fifty thousand of nearly five billion years), this is unwarranted self-inflation of the highest order.

Lyell and Wallace both preached a form of preparation; virtually all builders of picket fences have done so. Lyell depicted an earth in steady-state waiting, indeed almost yearning, for the arrival of a conscious being that could understand and appreciate its sublime and uniform design. Wallace, who turned to spiritualism later in life, advanced the more common claim that physical evolution had occurred in order, ultimately, to link pre-existing mind with a body capable of using it:

We, who accept the existence of a spiritual world, can look upon the universe as a grand consistent whole adapted in all its parts to the development of spiritual beings capable of indefinite life and perfectibility. To us, the whole purpose, the only

raison d'être

of the worldâwith all its complexities of physical structure, with its grand geological progress, the slow evolution of the vegetable and animal kingdoms, and the ultimate appearance of manâwas the development of the human spirit in association with the human body.

I think that all evolutionists would now reject Wallace's version of the argument for preparationâthe foreordination of man in the literal sense. But can there be a legitimate and modern form of the general claim? I believe that such an argument can be constructed, and I also believe that it is the wrong way to view the history of life.

The modern version chucks foreordination in favor of predictability. It abandons the idea that the germ of

Homo sapiens

lay embedded in the primordial bacterium, or that some spiritual force superintended organic evolution, waiting to infuse mind into the first body worthy of receiving it. Instead, it holds that the fully natural process of organic evolution follows certain paths because its primary agent, natural selection, constructs ever more successful designs that prevail in competition against earlier models. The pathways of improvement are rigidly limited by the nature of building materials and the earth's environment. There are only a few waysâperhaps only oneâto construct a good flyer, swimmer, or runner. If we could go back to that primordial bacterium and start the process again, evolution would follow roughly the same path. Evolution is more like turning a ratchet than casting water on a broad and uniform slope. It proceeds in a kind of lock step; each stage raises the process one step up, and each is a necessary prelude to the next.

Since life began in microscopic chemistry and has now reached consciousness, the ratchet contains a long sequence of steps. These steps may not be “preparations” in the old sense of foreordination, but they are both predictable and necessary stages in an unsurprising sequence. In an important sense, they prepare the way for human evolution. We are here for a reason after all, even though that reason lies in the mechanics of engineering rather than in the volition of a deity.

But if evolution proceeded as a lock step, then the fossil record should display a pattern of gradual and sequential advance in organization. It docs not, and I regard this failure as the most telling argument against an evolutionary ratchet. As I argue in essay 21, life arose soon after the earth itself formed; it then plateaued for as long as three billion yearsâperhaps five-sixths of its total history. Throughout this vast period, life remained on the prokaryotic levelâbacterial and blue green algal cells without the internal structures (nucleus, mitochondria, and others) that make sex and complex metabolism possible. For perhaps three billion years, the highest form of life was an algal matâthin layers of prokaryotic algae that trap and bind sediment. Then, about 600 million years ago, virtually all the major designs of animal life appeared in the fossil record within a few million years. We do not know why the “Cambrian explosion” occurred when it did, but we have no reason to think that it had to happen then or had to happen at all.

Some scientists have argued that low oxygen levels prevented a previous evolution of complex animal life. If this were true, the ratchet might still work. The stage remained set for three billion years. The screw had to turn in a certain way, but it needed oxygen and had to wait until prokaryotic photosynthesizers gradually supplied the precious gas that the earth's original atmosphere had lacked. Indeed, oxygen was probably rare or absent in the earth's original atmosphere, but it now appears that large amounts had been generated by photosynthesis more than a billion years before the Cambrian explosion.

Thus, we have no reason to regard the Cambrian explosion as more than a fortunate event that need not have occurred, either at all or in the way it did. It may have been a consequence of the evolution of the eukaryotic (nucleate) cell from a symbiotic association of prokaryotic organisms within a single membrane. It may have occurred because the eukaryotic cell could evolve efficient sexual reproduction, and sex distributes and rearranges the genetic variability that Darwinian processes require. But the crucial point is this: if the Cambrian explosion could have occurred any time during more than a billion years before the actual eventâthat is, for about twice the amount of time that life has spent evolving since thenâa ratchet scarcely seems to be an appropriate metaphor for life's history.

If we must deal in metaphors, I prefer a very broad, low and uniform slope. Water drops randomly at the top and usually dries before flowing anywhere. Occasionally, it works its way downslope and carves a valley to channel future flows. These myriad valleys could have arisen anywhere on the landscape. Their current positions are quite accidental. If we could repeat the experiment, we might obtain no valleys at all, or a completely different system. Yet we now stand at the shore line contemplating the fine spacing of valleys and their even contact with the sea. How easy it is to be misled and to assume that no other landscape could possibly have arisen.

I confess that the metaphor of the landscape contains one weak borrowing from its rival, the ratchet. The initial slope does impart a preferred direction to the water dropping on topâeven though almost all drops dry before flowing and can flow, when they do, along millions of paths. Doesn't the initial slope imply weak predictability? Perhaps the realm of consciousness occupies such a long stretch of shoreline that some valley would have to reach it eventually.

But here we encounter another constraint, the one that prompted this essay (though I have been, I confess, a long time in getting to it). Almost all drops dry. It took three billion years for any substantial valley to form on the earth's initial slope. It might have taken six billion, or twelve, or twenty for all we know. If the earth were eternal, we might speak of inevitability. But it is not.