The Panda’s Thumb (27 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Â

1. The structure of bone. Coldblooded animals cannot keep their body temperature at a constant level: it fluctuates in sympathy with temperatures in the outside environment. Consequently, coldblooded animals living in regions with intense seasonality (cold winters and hot summers) develop growth rings in outer layers of compact boneâalternating layers of rapid summer and slower winter growth. (Tree rings, of course, record the same pattern.) Warmblooded animals do not develop rings because their internal temperature is constant in all seasons. Dinosaurs from regions of intense seasonality do not have growth rings in their bones.

2. Geographic distribution. Large coldblooded animals do not live at high latitudes (far from the equator) because they cannot warm up enough during short winter days and are too large to find safe places for hibernation. Some large dinosaurs lived so far north that they had to endure long periods entirely devoid of sunlight during the winter.

3. Fossil ecology. Warmblooded carnivores must eat much more than coldblooded carnivores of the same size in order to maintain their constant body temperatures. Consequently, when predators and prey are about the same size, a community of coldblooded animals will include relatively more predators (since each one needs to eat so much less) than a community of warmblooded animals. The ratio of predators to prey may reach 40 percent in coldblooded communities; it does not exceed 3 percent in warmblooded communities. Predators are rare in dinosaur faunas; their relative abundance matches our expectation for modern communities of warmblooded animals.

4. Dinosaur anatomy. Dinosaurs are usually depicted as slow, lumbering beasts, but newer reconstructions (see essay 25) indicate that many large dinosaurs resembled modern running mammals in locomotor anatomy and the proportions of their limbs.

Â

But how can we view feathers as an inheritance from dinosaurs; surely no

Brontosaurus

was ever invested like a peacock. For what did

Archaeopteryx

use its feathers? If for flight, then feathers may belong to birds alone; no one has ever postulated an airborne dinosaur (flying pterosaurs belong to a separate group). But Ostrom's anatomical reconstruction strongly suggests that

Archaeopteryx

could not fly; its feathered forearms are joined to its shoulder girdle in a manner quite inappropriate for flapping a wing. Ostrom suggests a dual function for feathers: insulation to protect a small warmblooded creature from heat loss and as a sort of basket trap to catch flying insects and other small prey in a fully enclosed embrace.

Archaeopteryx

was a small animal. It weighed less than a pound, and stood a full foot shorter than the smallest dinosaur. Small creatures have a very high ratio of surface area to volume (see essays 29 and 30). Heat is generated over a body's volume and radiated out through its surface. Small warmblooded creatures have special problems in maintaining a constant body temperature since heat dissipates so quickly from their relatively enormous surface. Shrews, although insulated by a coat of hair, must eat nearly all the time to keep their internal fires burning. The ratio of surface to volume was so low in large dinosaurs that they could maintain constant temperatures without insulation. But as soon as any dinosaur or its descendant became very small, it would need insulation to remain warmblooded. Feathers may have served as a primary adaptation for constant temperatures in small dinosaurs. Bakker suggests that many small coelurosaurs may have been feathered as well. (Very few fossils preserve any feathers;

Archaeopteryx

is a great rarity of exquisite preservation.)

Feathers, evolved primarily for insulation, were soon exploited for another purpose in flight. Indeed, it is hard to imagine how feathers could have evolved if they never had a use apart from flight. The ancestors of birds were surely flightless, and feathers did not arise all at once and fully formed. How could natural selection build an adaptation through several intermediate stages in ancestors that had no use for it? By postulating a primary function for insulation, we may view feathers as a device for giving warmblooded dinosaurs an access to the ecological advantages of small size.

Ostrom's arguments for a descent of birds from coelurosaurian dinosaurs do not depend upon the warmbloodedness of dinosaurs or the primary utility of feathers as insulation. They are based instead upon the classical methods of comparative anatomyâdetailed part-by-part similarity between bones, and a contention that such striking resemblance must reflect common descent, not convergence. I believe that Ostrom's arguments will stand no matter how the hot debate about warmblooded dinosaurs eventually resolves itself.

But the descent of birds from dinosaurs wins its fascination in the public eye only if birds inherited their primary adaptations of feathers and warmbloodedness directly from dinosaurs. If birds developed these adaptations after they branched, then dinosaurs are perfectly good reptiles in their physiology; they should be kept with turtles, lizards, and their kin in the class Reptilia. (I tend to be a traditionalist rather than a cladist in my taxonomic philosophy.) But if dinosaurs really were warmblooded, and if feathers were their way of remaining warmblooded at small sizes, then birds inherited the basis of their success from dinosaurs. And if dinosaurs were closer to birds than to other reptiles in their physiology, then we have a classical structural argumentânot just a genealogical claimâfor the formal alliance of birds and dinosaurs in a new class, Dinosauria.

Bakker and Galton write: “The avian radiation is an aerial exploitation of basic dinosaur physiology and structure, much as the bat radiation is an aerial exploitation of basic, primitive mammal physiology. Bats are not separated into an independent class merely because they fly. We believe that neither flight nor the species diversity of birds merits separation from dinosaurs on a class level.” Think of

Tyrannosaurus

, and thank the old terror as a representative of his group, when you split the wishbone later this month.

*

From Nature's chain whatever link you strike,

Tenth, or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike.

Alexander Pope,

An Essay on Man

(1733)

P

OPE'S COUPLET EXPRESSES

a common, if exaggerated, concept of connection among organisms in an ecosystem. But ecosystems are not so precariously balanced that the extirpation of one species must act like the first domino in that colorful metaphor of the cold war. Indeed, it could not be, for extinction is the common fate of all speciesâand they cannot all take their ecosystems with them. Species often have as much dependence upon each other as Longfellow's “Ships that pass in the night.” New York City might even survive without its dogs (I'm not so sure about the cockroaches, but I'd chance it).

Shorter chains of dependence are more common. Odd couplings between dissimilar organisms form a stock in trade for popularizers of natural history. An alga and a fungus make lichen; photosynthetic microorganisms live in the tissue of reef-building corals. Natural selection is opportunistic; it fashions organisms for their current environments and cannot anticipate the future. One species often evolves an unbreakable dependency upon another species; in an inconstant world, this fruitful tie may seal its fate.

I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the fossil land snails of Bermuda. Along the shores, I would often encounter large hermit crabs incongruously stuffedâbig claw protrudingâinto the small shell of a neritid snail (nerites include the familiar “bleeding tooth”). Why, I wondered, didn't these crabs trade their cramped quarters for more commodious lodgings? After all, hermit crabs are exceeded only by modern executives in their frequency of entry into the real estate market. Then, one day, I saw a hermit crab with proper accommodationsâa shell of the “whelk”

Cittarium pica

, a large snail and major food item throughout the West Indies. But the

Cittarium

shell was a fossil, washed out of an ancient sand dune to which it had been carried 120,000 years before by an ancestor of its current occupant. I watched carefully during the ensuing months. Most hermits had squeezed into nerites, but a few inhabited whelk shells and the shells were always fossils.

I began to put the story together, only to find that I had been scooped in 1907 by Addison E. Verrill, master taxonomist, Yale professor, protégé of Louis Agassiz, and diligent recorder of Bermuda's natural history. Verrill searched the records of Bermudian history for references to living whelks and found that they had been abundant during the first years of human habitation. Captain John Smith, for example, recorded the fate of one crew member during the great famine of 1614â15: “One amongst the rest hid himself in the woods, and lived only on Wilkes and Land Crabs, fat and lusty, many months.” Another crew member stated that they made cement for the seams of their vessels by mixing lime from burned whelk shells with turtle oil. Verrill's last record of living

Cittarium

came from kitchen middens of British soldiers stationed on Bermuda during the war of 1812. None, he reported, had been seen in recent times, “nor could I learn that any had been taken within the memory of the oldest inhabitants.” No observations during the past seventy years have revised Verrill's conclusion that

Cittarium

is extinct in Bermuda.

As I read Verrill's account, the plight of

Cenobita diogenes

(proper name of the large hermit crab) struck me with that anthropocentric twinge of pain often invested, perhaps improperly, in other creatures. For I realized that nature had condemned

Cenobita

to slow elimination on Bermuda. The neritid shells are too small; only juvenile and very young adult crabs fit inside themâand very badly at that. No other modern snail seems to suit them and a successful adult life requires the discovery and possession (often through conquest) of a most precious and dwindling commodityâa

Cittarium

shell. But

Cittarium

, to borrow the jargon of recent years, has become a “nonrenewable resource” on Bermuda, and crabs are still recycling the shells of previous centuries. These shells are thick and strong, but they cannot resist the waves and rocks foreverâand the supply constantly diminishes. A few “new” shells tumble down from the fossil dunes each yearâa precious legacy from ancestral crabs that carried them up the hills ages agoâbut these cannot meet the demand.

Cenobita

seems destined to fulfill the pessimistic vision of many futuristic films and scenarios: depleted survivors fighting to the death for a last morsel. The scientist who named this large hermit chose well. Diogenes the Cynic lit his lantern and searched the streets of Athens for an honest man; none could he find.

C. diogenes

will perish looking for a decent shell.

This poignant story of

Cenobita

emerged from deep storage in my mind when I heard a strikingly similar tale recently. Crabs and snails forged an evolutionary interdependence in the first story. A more unlikely combinationâseeds and dodosâprovides the second, but this one has a happy ending.

William Buckland, a leading catastrophist among nineteenth-century geologists, summarized the history of life on a large chart, folded several times to fit in the pages of his popular work

Geology and Mineralogy Considered With Reference to Natural Theology

. The chart depicts victims of mass extinctions grouped by the time of their extirpation. The great animals are crowded together: ichthyosaurs, dinosaurs, ammonites, and pterosaurs in one cluster; mammoths, woolly rhinos, and giant cave bears in another. At the far right, representing modern animals, the dodo stands alone, the first recorded extinction of our era. The dodo, a giant flightless pigeon (twenty-five pounds or more in weight), lived in fair abundance on the island of Mauritius. Within 200 years of its discovery in the fifteenth century, it had been wiped outâby men who prized its tasty eggs and by the hogs that early sailors had transported to Mauritius. No living dodos have been seen since 1681.

In August, 1977, Stanley A. Temple, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Wisconsin, reported the following remarkable story (but see postscript for a subsequent challenge). He, and others before him, had noted that a large tree,

Calvaria major

, seemed to be near the verge of extinction on Mauritius. In 1973, he could find only thirteen “old, overmature, and dying trees” in the remnant native forests. Experienced Mauritian foresters estimated the trees' ages at more than 300 years. These trees produce well-formed, apparently fertile seeds each year, but none germinate and no young plants are known. Attempts to induce germination in the controlled and favorable climate of a nursery have failed. Yet

Calvaria

was once common on Mauritius; old forestry records indicate that it had been lumbered extensively.

Calvaria

's large fruits, about two inches in diameter, consist of a seed enclosed in a hard pit nearly half an inch thick. This pit is surrounded by a layer of pulpy, succulent material covered by a thin outer skin. Temple concluded that

Calvaria

seeds fail to germinate because the thick pit “mechanically resists the expansion of the embryo within.” How, then, did it germinate in previous centuries?

Temple put two facts together. Early explorers reported that the dodo fed on fruits and seeds of large forest trees; in fact, fossil

Calvaria

pits have been found among skeletal remains of the dodo. The dodo had a strong gizzard filled with large stones that could crush tough bits of food. Secondly, the age of surviving

Calvaria

trees matches the demise of the dodo. None has sprouted since the dodo disappeared almost 300 years ago.

Temple therefore argues that

Calvaria

evolved its unusually thick pit as an adaptation to resist destruction by crushing in a dodo's gizzard. But, in so doing, they became dependent upon dodos for their own reproduction. Tit for tat. A pit thick enough to survive in a dodo's gizzard is a pit too thick for an embryo to burst by its own resources. Thus, the gizzard that once threatened the seed had become its necessary accomplice. The thick pit must be abraded and scratched before it can germinate.

Several small animals eat the fruit of

Calvaria

today, but they merely nibble away the succulent middle and leave the internal pit untouched. The dodo was big enough to swallow the fruit whole. After consuming the middle, dodos would have abraded the pit in their gizzards before regurgitating it or passing it in their feces. Temple cites many analogous cases of greatly increased germination rates for seeds after passage through the digestive tracts of various animals.

Temple then tried to estimate the crushing force of a dodo's gizzard by making a plot of body weight versus force generated by the gizzard in several modern birds. Extrapolating the curve up to a dodo's size, he estimates that

Calvaria

pits were thick enough to resist crushing; in fact, the thickest pits could not be crushed until they had been reduced nearly 30 percent by abrasion. Dodos might well have regurgitated the pits or passed them along before subjecting them to such an extended treatment. Temple took turkeysâthe closest modern analogue to dodosâand force-fed them

Calvaria

pits, one at a time. Seven of seventeen pits were crushed by the turkey's gizzard, but the other ten were regurgitated or passed in feces after considerable abrasion. Temple planted these seeds and three of them germinated. He writes: “These may well have been the first

Calvaria

seeds to germinate in more than 300 years.”

Calvaria

can probably be saved from the brink of extinction by the propagation of artificially abraded seeds. For once, an astute observation, combined with imaginative thought and experiment, may lead to preservation rather than destruction.

I wrote this essay to begin the fifth year of my regular column in Natural History magazine. I said to myself at the beginning that I would depart from a long tradition of popular writing in natural history. I would not tell the fascinating tales of nature merely for their own sake. I would tie any particular story to a general principle of evolutionary theory: pandas and sea turtles to imperfection as the proof of evolution, magnetic bacteria to principles of scaling, mites that eat their mother from inside to Fisher's theory of sex ratio. But this column has no message beyond the evident homily that things are connected to other things in our complex worldâand that local disruptions have wider consequences. I have only recounted these two, related stories because they touched meâone bitterly, the other with sweetness.

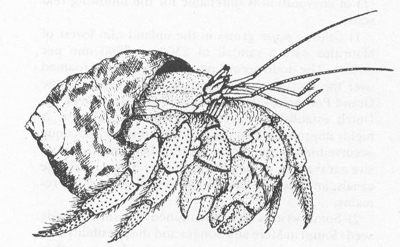

Coenobita diogenes

in the shell of

Cittarium

. Drawn from life by A. Verrill in 1900.

Postscript

Some stories in natural history are too beautiful and complex to win general acceptance. Temple's report received immediate publicity in the popular press (

New York Times

and other major newspapers, followed two months later by my article). A year later (March 30, 1979), Dr. Owadally of the Mauritian Forestry Service raised some important doubts in a technical comment published in the professional journal

Science

(where Temple's original article had appeared). I reproduce below, verbatim, both Owadally's comment and Temple's response:

I do not dispute that coevolution between plant and animal exists and that the germination of some seeds may be assisted by their passing through the gut of animals. However, that “mutualism” of the famous dodo and

Calvaria major

(tambalacoque) is an example (

1

) of coevolution is untenable for the following reasons.

1)

Calvaria major

grows in the upland rain forest of Mauritius with a rainfall of 2500 to 3800 mm per annum. The dodo according to Dutch sources roamed over the northern plains and the eastern hills in the Grand Port areaâthat is, in a drier forestâwhere the Dutch established their first settlement. Thus it is highly improbable that the dodo and the tambalacoque occurred in the same ecological niche. Indeed, extensive excavations in the uplands for reservoirs, drainage canals, and the like have failed to reveal any dodo remains.

2) Some writers have mentioned the small woody seeds found in Mare aux Songes and the possibility that their germination was assisted by the dodo or other birds. But we now know that these seeds are not tambalacoque but belong to another species of lowland tree recently identified as

Sideroxylon longifolium

.

3) The Forestry Service has for some years been studying and effecting the germination of tambalacoque seeds without avian intervention

(2)

. The germination rate is low but not more so than that of many other indigenous species which have, of recent decades, showed a marked deterioration in reproduction. This deterioration is due to various factors too complex to be discussed in this comment. The main factors have been the depredations caused by monkeys and the invasion by exotic plants.

4) A survey of the climax rain forest of the uplands made in 1941 by Vaughan and Wiehe

(3)

showed that there was quite a significant population of young tambalacoque plants certainly less than 75 to 100 years old. The dodo became extinct around 1675!

5) The manner in which the tambalacoque seed germinates was described by Hill

(4)

. who demonstrated how the embryo is able to emerge from the hard woody endocarp. This is effected by the swollen embryo breaking off the bottom half of the seed along a well-defined fracture zone.

It is necessary to dispel the tambalacoque-dodo “myth” and recognize the efforts of the Forestry Service of Mauritius to propagate this magnificent tree of the upland plateau.

A. W. O

WADALLY