The Paper Dragon (37 page)

Authors: Evan Hunter

"No, sir, they do not. Lieutenant Cooper is not supposed to be a fairy."

"Is Corporal Finlay supposed to be a fairy?"

"No, sir."

"And yet, he is based on Private Colman in the book, isn't that what you said?"

"That's what I said."

"Isn't Private Colman a homosexual?"

"No, sir."

"Not in your movie, I realize that. But how about the book?"

"I don't know what he is in the book."

"Surely you read the book?"

"Yes, of course I read the book."

"Then surely you are aware of the stream of consciousness passage — it is seven pages long, Mr. Knowles — wherein Private Colman clearly remembers and alludes to a homosexual episode with the dead major. Surely you remember reading that?"

"If I read it, I automatically discarded it as possible movie material. There is no homosexuality in any of my films, or even suggestions of homosexuality."

"But we do have a disturbed corporal whom the men rib about doing sissy work."

"Yes."

"Calling him names like 'honey' and 'sweetie'…"

"Yes."

"And suggesting that going into the lieutenant's tent might prove enjoyable."

"I didn't say that.

Nobody

says that. They only say he might enjoy the

paperwork.

"

"Is that what they actually mean? Paperwork?"

"Yes. They're kidding the lieutenant about the paperwork, about how he thinks it's enjoyable, they're belittling his idea of enjoyment."

"I see. And you intended no homosexual reference, either concerning the lieutenant

or

the corporal."

"Absolutely not."

"Let's get to the girl in your movie, shall we, Mr. Knowles?"

"Fine."

"You said that she invented the business with the mess kit while you were shooting the film, that it did not appear in your screenplay. Miss Tucker ad-libbed it on the set because your property man had neglected to include a mirror in her handbag."

"That's right."

"When you noticed the missing mirror, why didn't you stop the shooting?"

"Because the scene was going very well."

"Yes, but it was only a first take, wasn't it?"

"Of a very difficult shot."

"Well, surely you could have stopped the camera, and then given Miss Tucker a mirror, and continued shooting. Movies are a matter of splicing together scenes, anyway, aren't they?"

"That would have been impossible with this particular shot. If I had stopped the action, we would have had to go again from the top. Besides, as I told you, I didn't

want

to stop the action. The scene was going very well, and when I saw what Shirley was up to, I just let her go right ahead."

"Why would it have been impossible to stop this particular scene without starting again from the beginning of it?"

"The camera was on a boom and a dolly both. There was continuous action, the dolly moving in…"

"The dolly?"

"It's a… well, I guess you can call it a cart or a wagon on tracks, and the camera is mounted on it. As the scene progressed, the dolly was coming in closer and closer to Miss Tucker, and then as she picked up the lipstick we began to move up on the boom…"

"I'm afraid you'll have to tell me what a boom is also."

"It's a mechanical — well… a

lift

, I guess would describe it — that moves the camera up and down, vertically. When we were in close on her, we went for the boom shot, all without breaking the action. In other words, I wanted this scene to have a complete flow, without any cutting, and it was necessary to shoot it from top to bottom without stopping. That's why I let her use the mess kit. As it turned out, we got the scene in one take and were delighted with it. It's one of the best scenes in the movie, in fact."

"An ad-libbed scene?"

"Well, the part with the mess kit was ad-libbed."

"It was not in your screenplay?"

"No, sir."

"Would you turn to reel 5, page 2 of this, Mr. Knowles?"

"What?"

"Please. Reel 5, page 2."

"Yes?"

"Do you see the numeral 176, right after the lieutenant says, 'Colman's the one who's responsible for their anger and their hatred.' Read on after that, would you, from DS — which I assume means 'downstage.' "

"No, it means 'dolly shot.' It says, 'DS — JAN — AND INTO BOOM SHOT: She takes lipstick from her purse and then, finding no mirror, picks up a mess kit from the table, discovers that its back is shiny, and uses it as she applies her lipstick.' "

"Now you testified that this scene was ad-libbed. Yet right here in your screenplay…"

"This is

not

my screenplay," Ralph said.

"It has your name on it."

"It's the cutting continuity of the film."

"Isn't that the same as.?"

"No, sir. This is the

cutting

continuity, reel by reel. It's a record of all the action and dialogue in the film as it was shot. The cutter put this together."

"From the shooting script?"

"No, sir, from the completed

film

."

"Exactly as it was shot?"

"Exactly. But this is not a screenplay. This was not in existence until the film was finally completed."

"It is nonetheless a script, no matter what you choose to call—"

"No, sir, it is the continuity of the actual

film

. It is not a script in any sense of the word."

"But it nonetheless shows exactly what happened on the screen?"

"Yes."

"And what happened on the screen was that the girl used a mess kit for a mirror."

"Yes."

"That's all, thank you."

"Have you concluded your cross, Mr. Brackman?"

"I have, your Honor."

"Any further questions?"

"None, your Honor," Genitori said.

"None," Willow said.

"Thank you, Mr. Knowles," McIntyre said.

"Thank

you

, sir," Ralph said.

"Your Honor, Mr. Knowles is on his way to the Orient where he is beginning a new film. Would it be possible to release him at this point?"

"Certainly."

"Thank you," Ralph said, and rose and began walking toward the jury box. Behind him, he could hear the judge telling everyone that it was now ten minutes to four, and then asking Willow whether he wanted to begin his direct examination of James Driscoll now or would he prefer waiting until morning. Willow replied that he would rather wait until morning, and McIntyre commented that this was probably best since he thought they were all a bit weary, and then the clerk said something about the court reconvening at ten in the morning, and Ralph kept walking toward the jury box and then realized that everyone was rising to leave the courtroom and turned instead to head for the bronze-studded doors. He was very pleased with himself, and he nodded and smiled at Driscoll, who was rising and moving out of the jury box, and then he glanced over his shoulder to see Genitori rising from behind the defense table and moving very quickly toward him, and he continued smiling as he opened the door because he knew without a doubt that he had performed beautifully and perhaps saved this miserable little trial from total obscurity.

"You're a son of a bitch," Genitori said.

"What?" Ralph said. "What?"

"You heard me, you prick!"

"What? What?"

He had wedged Ralph into a corner of the corridor, and now he leaned toward him in fury, his fists bunched at his sides, his arms straight, his face turned up, eyes glaring, as though he were restraining himself only with the greatest of effort. He is very comical, Ralph thought, this little butterball of a man with his balding head and pale blue eyes, hurling epithets, I could flatten him with one punch — But he did not raise his hands because there was something terrifying about Genitori's anger, and Ralph knew without question that the lawyer could commit murder here in this sunless corridor, and he had no intention of provoking his own demise.

"What's the matter with you?" he said. "Now calm down, will you? What's the matter with you?"

"You son of a bitch," Genitori said.

"Look, now let's watch the language, do you mind? You're…"

"What do you think we're doing here? You think we're playing

games

here, you son of a bitch?"

"Now look…"

"Shut up!"

"Look, Sam…"

"Shut up, you egocentric asshole!"

The juxtaposition of adjective and noun amused Ralph, but he did not laugh. The anger emanating from Genitori was monumental, it was awesome, it was classic. He knew that a laugh, a smile, even a mere upturning of his lips might trigger mayhem, so he tried to ease his way out of the cul-de-sac into which Genitori had wedged him, but the walls on either side of him were immovable and Genitori blocked his path like a small raging bull about to lower his horns and charge.

"Now take it easy," Ralph said.

"What did we discuss last night, you miserable bastard?" Genitori said. "Why did I drive all the way to Idlewild…"

"Kennedy."

"You son of a bitch, don't correct me, you miserable jackass! All the way in from Massapequa, you think I

enjoy

midnight rides?"

"Now look, Sam…"

"Don't look

me

, you moron! There's a man's career at stake in that courtroom, we're not kidding around here! We lose this case, and James Driscoll goes down the drain!"

"What did I

do

, would you mind…"

"What

didn't

you do? You gave them everything they wanted!"

"How? All I…"

"

Is

there a homosexual colonel in that goddamn play?"

"What?"

"I said—"

"How do

I

know? I didn't say there was a—"

"Well, there

isn't

. But you were so busy denying even the

suggestion

of one in your movie…"

"How was I supposed to know…"

"Is even the

suggestion

threatening to you?"

"Now look here, Sam, nothing about homosexuality threatens

me

, so let's not…"

"Then why did you insist a clearly homosexual scene

wasn't

one?"

"I told the truth as I saw it!"

"Yes, and make it sound as if you were hiding a

theft

."

"I didn't intend…"

"Were you also telling the truth about dividing Colman into two characters?"

"Of course. What's wrong with that? I was explaining…"

"It's exactly what they

claimed

was done."

"Huh?"

"Huh, huh? They said Driscoll changed it when he copied the play, and you changed it right back again.

Huh

?"

"I did?"

"That's what you

admitted

doing, isn't it, you stupid ass!"

"I was under oath. I had to explain how I wrote the screenplay. That's what he asked me, and that's what I had to tell him."

"Do you even

remember

how you wrote it?"

"Yes. Just the way I said I did."

"I don't believe you. I think if Brackman said you'd made

fifteen

characters out of Colman, you'd have agreed."

"Now why would I do anything like that, Sam?"

"To show that your movie was an original act of creation, something that just happened to pop into your head, the hell with Driscoll and his book, you practically ad-libbed the whole movie on the set!"

"I never said that! The" only scene we ad-libbed was the one with the mess kit. How was I to know all this other stuff was so—"

"Why didn't you read the play, the way we asked you to?"

"I have better things to do with my time."

"Like what? Destroying the reputation of a better writer than you'll ever be?"

"Now that's enough, Sam. You can't—"

"Don't get me sore, you… you

porco fetente

" Geni-tori said, apparently having run out of English expletives. "You've done more toward killing this case…"

"Look, Sam…"

"… than any witness the

plaintiff

might have called!"

"Look, Sam, I don't have to listen to this," Ralph said, having already listened to it.

"No, you don't, that's true. All you have to listen to is that tiny little voice inside your head that keeps repeating, 'Ralph Knowles, you are wonderful, Ralph Knowles, you are marvelous.' That's all you have to listen to. Are you flying?"

"What? Yes."

"Good. I hope your goddamn plane crashes," Genitori said, and then turned on his heel and went raging down the corridor.

Boy, Ralph thought.

10

He saw her for the first time in Bertie's on DeKalb Avenue, a girl with short blond hair, wearing sweater and skirt, scuffed loafers, her elbow on the table, her wrist bent, a cigarette idly hanging in two curled fingers. Unaware of him, she laughed at something someone at her table said, and then dragged on the cigarette, and laughed again, and picked up her beer mug, still not looking at him while he continued to stare at her from the door. He took off his parka and hung it on a peg, and then went to join some of the art-student crowd jammed elbow to elbow at the bar. Some engineering students at the other end of the long, narrow room were beerily singing one of the popular sentimental ballads. He watched her for a moment longer, until he was sure she would not return his glance, and then wedged himself in against the bar with his back to her, and ordered a beer. The place smelled of youthful exuberant sweat, and sawdust, and soap, and booze, and of something he would have given his soul to capture on canvas in oil, a dank November scent that seemed to seep from the windswept Brooklyn street outside and into the bar.

He knew all at once that she had turned to look at him.

He could not have said how he knew, but he sensed without doubt that she had discovered him and was staring at him, and he suddenly felt more confident than he ever had in his life. Without hesitating to verify his certain knowledge, he turned from the bar with the beer mug in his hand and walked directly across the room toward her table — she was no longer looking at him-and pulled out the chair confidently without even glancing at any of the other boys or girls sitting there, nor caring whether they thought he was nuts or whatever, but simply sat and put down his beer mug, and then looked directly at her as she turned to face him.

"My name is Jimmy Driscoll," he said.

"Hello, Jimmy Driscoll," she answered.

"What's

your

name?"

"Goodbye, Jimmy Driscoll," one of the boys at the table said.

"Ebie Dearborn," she said.

"Hello, Ebie. You're from Virginia, right?"

"Wrong."

"Georgia?"

"Nope."

"Where?"

"Alabama."

"It figures."

"What do you mean?"

"Honey chile, that's

some

accent you-all got there."

"Don't make fun of it," she said, and then turned toward her friends as laughter erupted from the other end of her table. "What was it?" she asked them, smiling in anticipation. "I

missed

it, what was it?"

"Ah-ha, you just try and find out," one of the boys said, and they all burst out laughing again.

"Would you like a beer?" he asked.

"All right," she said.

"Waiter, two beers," he said over his shoulder.

"Who'd you just order from?" she asked, and laughed.

"I don't know. Isn't there a waiter back there someplace? Two beers!" he yelled again, without looking behind him.

"Come and get them!" the bartender yelled back.

"You think you'll miss me?"

"Huh?"

"When I go for the beers."

"I doubt it. There's lots of company here."

"You may be surprised."

"I may be," she said.

He went to the bar and returned with two mugs of beer. She was in conversation with her friends when he approached, but she immediately turned away from them and pulled out a chair for him.

"How'd it work out?" he asked.

"I missed you, sure enough."

"I knew you would."

"Here's to your modest ways," she said, and raised her glass.

"Here's to your cornflower eyes."

"Mmm."

"How's the beer?"

"Fine."

"Would you like another one?"

"I've just barely sipped on this one."

"So what? Let me get another one for you."

"Not yet."

"Do you always wear your hair so short?"

"I cut it yesterday. Why? What's the matter with it?"

"You look shaggy."

"Say, thanks."

"I meant that as a compliment. I should have…"

"What

else

don't you like about me?"

"… said windblown."

"What?"

"Your hair. Windblown."

"Oh," she said, and brushed a strand of it away from her cheek.

"That's nice."

"What is?"

"What you just did. How old are you?"

"Nineteen."

"That's good."

"Why?"

"Older women appeal to me."

"What do you mean? How old are

you

?"

"Eighteen."

"Oh? Really?"

"I'm a first-year student."

"Oh?"

"But very advanced for my age."

"Yes, I can see that."

"You think this'll work out?"

"What do you mean?"

"I don't know, the age difference, the language barrier…" He smiled hopefully, and let the sentence trail.

"Frankly, I don't think it has a chance," she said, and did not return his smile.

"Let me get you another beer."

"I'm not ready for one yet."

"I'll get you one, anyway."

"I'm really not that thirsty."

"It doesn't matter. I'm the last of the big spenders," he said, and smiled again, but she only glanced toward her friends, who had begun a lively discussion about Mies. "Well, I'll get one for you."

"Suit yourself," she said, and shrugged.

He rose and went for the beer, half afraid she would leave the table while he was gone, aware that he was losing her, desperately searching in his mind for something to say that would salvage the situation, wondering where he had made his mistake, should he not have told her he was eighteen? or kidded her about the accent? if only he could think of a joke or an anecdote, something that would make her laugh. "One beer," the bartender said, and he picked it up and walked back to the table with it.

"Drink it quick before the foam disappears," he said, but she did not pick up the mug, and they sat in silence as the bubbles of foam rapidly dissipated, leaving a flat smooth amber surface an inch below the rim of the mug.

"Tell me about yourself," he said.

"My hair is shaggy," she said, "and I have a thick Southern accent, and…"

"Well, I know all that," he said, and realized at once he was pursuing the same stupid line, the wrong line, and yet seemed unable to stop himself. "Isn't there anything

interesting

you can add?"

"Oh, shut up," she said.

"What?"

"Just shut up."

"Okay," he said, but he could not remain silent for long. "We're having our first argument," he said, and smiled.

"Yes, and our last," she answered, and began to turn away from him. He caught her hand immediately.

"Come out with me this Saturday night," he said.

"I'm busy."

"Next Saturday."

"I'm busy then, too."

"The Saturday after…"

"I'm busy every Saturday until the Fourth of July. Let go of my hand, please."

"You'll be sorry," he said. "I'm going to be a famous artist."

"I'm sure."

"Come out with me."

"No."

"Okay," he said, and released her hand, and rose, and walked back to the bar.

He knew then perhaps, or should have known then, that it was finished, that there was no sense in a pursuit that would only lead to the identical conclusion, postponed. But he found himself searching for her on the windswept campus, Ryerson and Emerson, the malls and the parking lots, Steuben Walk in front of the Engineering Building, and then in the halls and classrooms themselves, and even on the Clinton-Washington subway station. In his notebook, he wrote:

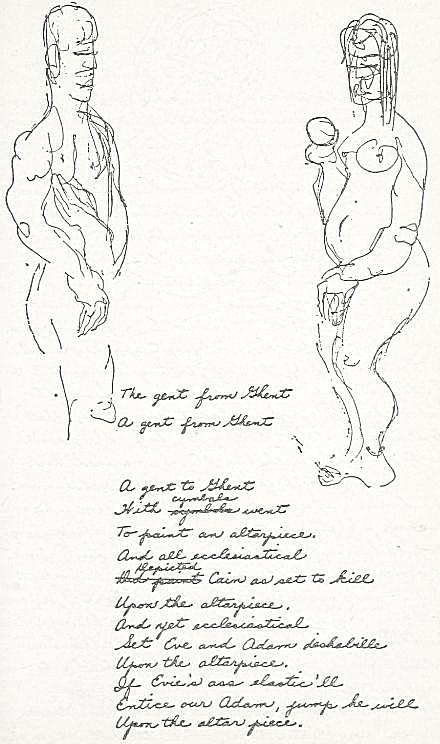

The notebook, which he had begun in October, and which he would continue to keep through the next several years, was a curious combination of haphazard scholarship, personal jottings, disjointed ideas and notions, doo-dlings, line drawings, and secret messages written in a code he thought only he could decipher. He had learned from his uncle a drawing technique that served him well all through high school, though it was later challenged by his instructor at the League. Revitalized provisionally at Pratt, it was an instant form of representation that sometimes veered dangerously close to cartoon exposition. But it nonetheless enabled him to record quickly and without hesitation anything that came into his line of vision. The technique, however, candid and loose, did not work too well without a model, and as his memory of the girl he'd met only once began to fade, he found himself relying more and more upon language to describe her and his feelings about her. A struggle for expression seemed to leap from the pages of the notebook, paragraphs of art history trailing into a personal monologue, or a memorandum, or a query, and then a sketch, and now a poem or an unabashed cartoon, and then again into desperate prose, until the pages at last were overwhelmed with words: