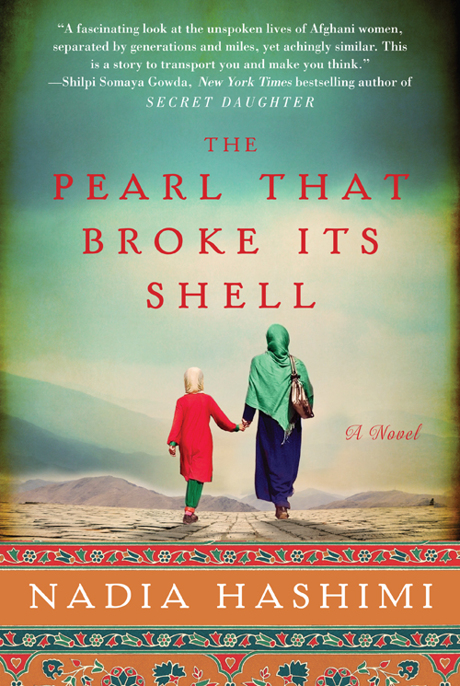

The Pearl that Broke Its Shell

Read The Pearl that Broke Its Shell Online

Authors: Nadia Hashimi

To my precious daughter, Zayla. To our precious daughters.

Seawater begs the pearl

To break its shell

—FROM THE ECSTATIC POEM

“

S

OME

K

ISS

W

E

W

ANT,”

BY

J

ALAL AD-

D

IN

M

OHAMMAD

R

UMI,

THIRTEENTH-CENTURY

P

ERSIAN POET

Contents

S

hahla stood by our front door, the bright green metal rusting on the edges. She craned her neck. Parwin and I rounded the corner and saw the relief in her eyes. We couldn’t be late again.

Parwin shot me a look and we picked up our hurried pace. We did the best we could without running. Rubber soles slapped against the road and raised puffs of dusty smoke. The hems of our skirts flapped against our ankles. My head scarf clung to beads of sweat on my forehead. I guessed Parwin’s was doing the same, since it hadn’t yet blown away.

Damn them. It was their fault! Those boys with their shameless grins and tattered pants! This wasn’t the first time they’d made us late.

We ran past the doors, blue, purple, burgundy. Spots of color on a clay canvas.

Shahla waved us toward her.

“Hurry!” she hissed frantically.

Panting, we followed her through the front door. Metal clanged against the door frame.

“Parwin! What did you do that for?”

“Sorry, sorry! I didn’t think it would be that loud.”

Shahla rolled her eyes, as did I. Parwin always let the door slam.

“What took you so long? Didn’t you take the street behind the bakery?”

“We couldn’t, Shahla! That’s where he was standing!”

We had gone the long way around the marketplace, avoiding the bakery where the boys loitered, their shoulders hunched and their eyes scouting the khaki jungle that was our village.

Besides pickup games of street soccer, this was the main sport for school-age boys—watching girls. They hung around waiting for us to come out of our classrooms. Once off school grounds, a boy might dart between cars and pedestrians to tail the girl who’d caught his eye. Following her helped him stake his claim.

This is my girl,

it told the others,

and there’s only room for one shadow here

. Today, my twelve-year-old sister, Shahla, was the magnet for unwanted attention.

The boys meant it to be flattering. But it frightened the girl since people would have loved to assume that she’d sought out the attention. There just weren’t many ways for the boys to entertain themselves.

“Shahla, where is Rohila?” I whispered. My heart was pounding as we tiptoed around to the back of the house.

“She’s taken some food to the neighbor’s house. Madar-

jan

cooked some eggplant for them. I think someone died.”

Died? My stomach tightened and I turned my attention back to following Shahla’s footsteps.

“Where’s Madar-

jan

?” Parwin said, her voice a nervous hush.

“She’s putting the baby to sleep,” Shahla said, turning toward us. “So you better not make too much noise or she’ll know you’re just coming home now.”

Parwin and I froze. Shahla’s face fell as she looked at our widened eyes. She whipped around to see Madar-

jan

standing behind her. She had come out of the back door and was standing in the small paved courtyard behind the house.

“Your mother is very much aware of exactly when you girls have gotten home and she is also very much aware of what kind of example your older sister is setting for you.” Her arms were folded tightly across her chest.

Shahla’s head hung in shame. Parwin and I tried to avoid Madar-

jan

’s glare.

“Where have you been?”

How badly I wanted to tell her the truth!

A boy, lucky enough to have a bicycle, had followed Shahla, riding past us and then circling back and forth. Shahla paid no attention to him. When I whispered that he was looking at her, she hushed me, as if speaking it would make it true. On his third pass, he got too close.

He looped ahead of us and came back in our direction. He raced down the dirt street, slowing down as he neared us. Shahla kept her eyes averted and tried to look angry.

“Parwin, watch out!”

Before I could push her out of the way, the cycling stalker’s front wheel rolled over a metal can in the street; he veered left and right, then swerved to avoid a stray dog. The bicycle came straight at us. The boy’s eyebrows were raised, his mouth open as he struggled to regain balance. He swiped Parwin before toppling over on the front steps of a dried-goods shop.

“Oh my God,” Parwin exclaimed, her voice loud and giddy. “Look at him! Knocked off his feet!”

“Do you think he’s hurt?” Shahla said. She had her hand over her mouth, as if she had never seen a sight so tragic.

“Parwin, your skirt!” My eyes had moved from Shahla’s concerned face to the torn hem of Parwin’s skirt. The jagged wires holding the spokes of the bicycle together had snagged Parwin’s dress.

It was her new school uniform and instantly Parwin began to weep. We knew if Madar-

jan

told our father, he would keep us home instead of sending us to school. It had happened before.

“Why are you all silent only when I ask you something? Do you have nothing to say for yourselves? You come home late and look like you were chasing dogs in the street!”

Shahla had spoken on our behalf plenty of times and looked exasperated. Parwin was a basket of nerves, always, and could do nothing but fidget. I heard my voice before I knew what I was saying.

“Madar-

jan,

it wasn’t our fault! There was this boy on a bicycle and we ignored him but he kept coming back and I even yelled at him. I told him he was an idiot if he didn’t know his way home.”

Parwin let out an inadvertent giggle. Madar-

jan

shot her a look.

“Did he come near you?” she asked, turning to Shahla.

“No, Madar-

jan

. I mean, he was a few meters behind us. He didn’t say anything.”

Madar-

jan

sighed and brought her hands to her temples.

“Fine. Get inside and start your homework assignments. Let’s see what your father says about this.”

“You’re going to tell him?” I cried out.

“Of course I am going to tell him,” she answered, and spanked my backside as I walked past her into the house. “We are not in the habit of keeping things from your father!”

We whispered about what Padar-

jan

would say when he came home while we dug our pencils into our notebooks. Parwin had some ideas.

“I think we should tell Padar that our teachers know about those boys and that they have already gotten in trouble so they won’t be bothering us anymore,” Parwin suggested eagerly.

“Parwin, that’s not going to work. What are you going to say when Madar asks Khanum Behduri about it?” Shahla, the voice of reason.

“Well, then we could tell him that the boy said he was sorry and promised not to bother us again. Or that we are going to find another way to get to school.”

“Fine, Parwin. You tell him. I’m tired of talking for all of you anyway.”

“Parwin’s not going to say anything. She only talks when no one’s listening,” I said.

“Very funny, Rahima. You’re so brave, aren’t you? Let’s see how brave you are when Padar-

jan

comes home,” Parwin said, pouting.

Granted, I wasn’t a very brave nine-year-old when it came time to face Padar-

jan

. I kept my thoughts bottled behind my pursed lips. In the end, Padar-

jan

decided to pull us out of school again.

We begged and pleaded with Padar-

jan

to let us return to school. One of Parwin’s teachers, a childhood friend of Madar-

jan,

even showed up at the house and tried to reason with our parents. Padar-

jan

had relented in the past but this time was different. He wanted us to go to school but struggled with how to make that happen safely. How would it look for his daughters to be chased by local boys for all to see? Awful.

“If I had a son this would not be happening! Goddamn it! Why do we have a house full of girls! Not one, not two—but five of them!” he would yell. Madar-

jan

would busy herself with housework, feeling the weight of disappointment on her shoulders.

His temper was worse these days. Madar-

jan

would tell us to hush and be respectful. She told us too many bad things had happened to Padar-

jan

and it had made him an angry man. She said if we all behaved then he would go back to being his normal self soon. But it was getting harder and harder to remember a time when Padar-

jan

wasn’t angry and loud.

Now that we were home, I was given the extra chore of bringing the groceries from the store. My older sisters were quarantined since they were older and noticeable. I was, thus far, invisible to boys and not a risk.

Every two days I stuffed a few bills from Madar-

jan

in the pouch that she had sewn into my dress pocket so I would have no excuse for losing them. I would wind my way through the narrow streets and walk thirty minutes to reach the market I loved. The stores were bustling with activity. Women looked different now than they had a few years ago. Some wore long blue

burqas

and others wore long skirts and modest head scarves. The men all dressed like my father, long tunics with billowing pantaloons—colors as drab as our landscape. Little boys wore ornate caps with small round mirrors and gold scrolling. By the time I got there, my shoes were again dusty and I would resort to using my head scarf as a filter for the clouds of dirt the hundreds of cars left in their wake. It was as if the khaki-colored landscape were dissolving into the air of our village.