The Pentagon: A History (34 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

Drivers who did make it to the building found parking saturated. By June, spaces had been paved for three thousand cars, but with nearly twenty thousand construction workers and War Department employees, they went fast. Those who were able to find a spot often would have trouble finding their cars after work. A layer of fine Virginia clay dust stirred up by the construction coated every vehicle in the lot, giving them all the same orange-red color. Robert Sanders, a Services of Supply employee, took to tying a colored ribbon to his radio antenna so he could spot his car.

Traveling by bus was not a pleasant option. Nelson Clayton, an eighteen-year-old from the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains working as a telephone installer, paid a nickel every morning for an adventurous bus ride from his sister’s home in Arlington. “You’d ride the bus in, if they could find a way in,” Clayton recalled. “But they’d get lost, the roads would change, they’d stop out in the middle of the fields and you’d have to walk in through the mud. ‘There’s the building, we don’t know how to get there.’ You’d hike in half a mile maybe.”

In the evening, employees swarmed out of the building and into long lines to cram onto scarce buses. “Girls would smack each other over the head with their purses to get into the buses,” secretary Marie Dowling Owen later said. Most were left behind, coated with dust.

The Capital Transit Company, the largest of three private companies that served the building, had thirty-five buses, about two hundred short of what they would need once the building was finished. There was little immediate prospect of getting more, since the War Production Board had frozen the manufacture of buses. Those that existed were mostly wheezing old heaps. The ancient red bus Hanshaw rode home one day was unable to even climb up Columbia Pike. She and the other passengers got off and walked so the bus could make it up the hill.

Getting to and from the building was such a nightmare that a War Department official suggested the top two floors be converted into dormitories. Numerous war workers demanded transfers to other agencies to escape the Pentagon; others resigned from the government altogether. Plank walkers were going public with their criticisms. “Some may reproach us, and some do, for complaining about working conditions when our boys are dying in fox-holes,” an anonymous war worker wrote in a letter to the

Times-Herald

published September 5.

However we would like to inform the general public about our working conditions. Primarily we spend approximately three hours daily traveling to and from work.

We don’t mind the crowded conditions of the transportation vehicles, for we have already completed our course in the sardine stance. We don’t mind the poor air conditioning that causes one to perspire during the hot weather…. We don’t mind catching apermanent cold or dying of rheumatism. We wouldn’t mind the devil himself if we might be able to buy a decent lunch during our half hour recreation period.

The situation here is tragic. When this building is completed forty thousand people will be employed within this geometric castle. Forty thousand people ill-housed and ill-fed. The Army marches on its stomach—what about the War Department?

The most fantastic operation

General George Marshall, at least, did not think the situation entirely tragic. Throughout the construction, Marshall had been a frequent visitor to the Pentagon, often trotting down from Fort Myer during his evening horseback ride on Prepare, his chestnut gelding, to watch the progress. He and Somervell toured the building in August, and Marshall declared himself impressed with the cafeteria. On a September morning a few weeks later, Renshaw warned Paul Hauck that Marshall would be arriving in thirty minutes to inspect the Pentagon with a visitor. Marshall wanted to show off the building to British Field Marshal Sir John Dill, chief of the British military delegation in Washington. Personable and forthright, Dill had forged a close relationship with the Americans, particularly the Army chief of staff, and he had single-handedly improved the tenor of British–U.S. military cooperation.

Hauck took Marshall and Dill up to the roof, where they could see the entire project. Reaching the edge, the generals looked over a vast panorama of men and bulldozers, trucks and steam shovels moving in every direction, raising spirals of dust. The building was more than 80 percent complete and now home to about seventeen thousand war workers. Concrete was being poured for the upper floors of Section E, the last of the five sections. Workers were constructing the fifth floor atop the interior rings. All around the Pentagon, they could see a bewildering mix of half-built roads, intersections, and overpasses—many of them standing incongruously alone, like bridges in a desert.

Marshall and Dill surveyed the scene without speaking. The longer they looked, the more nervous Hauck grew. Finally Marshall asked Dill for his impressions. After a pause, Dill replied. “George, I’m speechless,” he said. “This is the most fantastic operation I have ever witnessed. It’s unbelievable.” The Pentagon, he told Marshall, was one of the most amazing buildings in the world. The building made a further impression on the visitors when Marshall and Dill wandered down a corridor with David Witmer, the chief architect, and were soon entirely lost. Hauck managed to track down the party and rescue the heart of the Anglo-American military alliance.

Even before its completion, the Pentagon was entering the national consciousness as a vast, unfathomable maze. A soon-to-be-famous joke made its first known appearance in print on August 17 in the

Washington Post:

“And have you heard this one? About the War Department messenger who got lost in the Pentagon Building in Arlington and came out a lieutenant colonel.” Almost everyone had heard it before long. It was told on the radio and in wire service accounts appearing across the United States. With time, the joke evolved and generally involved a freckled-faced Western Union messenger boy who went into the Pentagon to deliver a telegram on Monday and walked out Friday a full colonel; others insisted he came out a major. Another popular story told of a visitor who was hopelessly lost in the Pentagon. Sitting down at an empty desk to rest his feet, he was promptly outfitted with a phone, blotter, desk set, and secretary.

Soon after Marshall and Dill went missing, large wooden pentagonal-shaped maps showing the building floor plans were put up in all corridors, with arrows identifying the viewer’s location. They only helped a little. Lieutenant Katharine Stull, a Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps officer from Muskogee, Oklahoma, was striding down a Pentagon corridor when she noticed an Army captain staring uncomprehendingly at a wall map.

“Sir, may I help you?” Stull asked.

“Lady, I’m lost,” the captain responded. “But don’t tell me where to go. Lead me by the hand!”

Among all the visitors to the Pentagon that summer, perhaps none was more bewildered than an investigator sent by the Bureau of the Budget, the White House agency headed by Harold Smith, who had been so skeptical of Somervell’s project in the first place. The unnamed investigator was not lost, but he did spend five days in August inspecting the project, reviewing plans, specifications, and official records, and interviewing McShain, Renshaw, and others. What he learned shocked him. By his calculations, the building would reach an estimated size of 6.6 million gross square feet, which was far bigger than what had been initially proposed. Groves had told the congressional committee in June that the building was four million gross square feet, a figure the War Department repeated in a press release in July. Even Somervell’s original, grandiose proposal a year earlier had encompassed only 5.1 million gross square feet, before it was cut back under pressure.

Moreover, the investigator figured, the Pentagon’s cost was far beyond the $35 million approved by Congress a year earlier. It was far beyond the $49 million cost that Somervell had reported to Congress in May. It was $25 million beyond that, in fact.

“This project, with its building, access roads, parking areas, landscaping, terraces, utilities, all estimated to cost in excess of $74,000,000…is an entirely different project than that which was placed before Congress during the summer of 1941,” the investigator wrote in his August 31, 1942, report, which was not made public.

The only similarity between the building, as proposed, and that now being constructed is its intended use. The location of the site, the design and architecture of the building, and the cost of the project or building is in no way similar to that which was presented to Congress.

Information as to who was directly responsible for the radical change is very meagre.

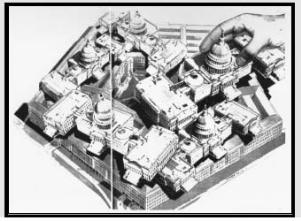

1943 illustration from

Popular Mechanics

showing how many Capitol buildings could fit into the Pentagon.

Washington’s demon investigator

Albert Engel had a pretty good idea who might be responsible. Like the anonymous investigator from the Bureau of the Budget, Engel, a Republican congressman from Michigan, had been poking around the Pentagon construction site over the summer of 1942. As fall approached, Engel was taking dead aim at Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somervell.

Engel was “Washington’s demon one-man investigating committee,” in the words of the

Saturday Evening Post.

The “mop-haired, jug-shaped” congressman specialized in dropping in unexpectedly on Army camps, munitions plants, and other military installations under construction around the country. Engel would cram his 5' 7? 235-pound body behind the steering wheel of his car and take off for days or weeks, his stuffed briefcase and a paper sack with sandwiches and an apple on the seat next to him. To avoid tipping off his presence, Engel would arrive in town around dusk and find accommodations in a rooming house or a fleabag hotel. More often than not, workers at the plant he was investigating would be staying there too, and they would be quizzed by the visitor. By midnight, Engel would station himself at a neighborhood hamburger joint, pumping workers coming off the evening shift for more intelligence. After a few hours’ sleep, he would be up at dawn and report to work with the morning shift.

By the time authorities learned of his presence, it would be too late. Armed with his findings, Engel would interrogate the project’s officers and contractors, taking voluminous notes with a stubby pencil on ruled yellow paper and typing them up at night. By sundown he would be on his way to the next project on his list. “Usually, they fire off a sixteen-gun salute, wine and dine you and then say ‘Goodbye and God bless you,’ but I went in as a worker and talked with everyone—a time-keeper here, a carpenter there, and I took a picture here and there,” he proudly said.

Engel was nothing if not dogged. During one extended tour of defense plants, his car broke down and he left it at a repair shop in Detroit. Engel continued to Ohio in a new automobile, but was struck by a train as he crossed railroad tracks. The car was destroyed and Engel was rushed to a hospital in Akron suffering lacerations to his scalp and two black eyes.

“No anesthetic,” Engel told the emergency room physician. “I’m in sort of a hurry.” An hour and twenty-two stitches later, Engel was on his way in a taxicab to the train station, ready to resume his journey.

In early 1941, after discovering that the Army was running a deficit of more than $300 million in its construction program, Engel launched his most ambitious tour yet. Somervell, then head of the Construction Division, solicitously offered to arrange the trip for Engel and provide an Army officer to serve as his guide (and doubtless as a spy for Somervell), but the congressman would have none of it. Over the course of several weeks, driving alone through snow and weather as cold as fifteen degrees below zero, Engel covered fourteen thousand miles and made unannounced visits to thirteen construction projects from upstate New York to northern Florida. “He had four generals backed into a corner, peppering them with questions,” said a fellow congressman who happened to be visiting Fort Bragg, North Carolina, at the same time as Engel in mid-February. “They looked as if they would rather have been facing a firing squad.” An officer at Fort Bragg telephoned Groves to warn that Engel planned to attack the Construction Division when he returned to Washington. “Encourage him to go further away,” Groves replied.

Engel did make it back to Washington and presented his findings on the floor of the House on April 3, 1941, mincing no words. “I say here and now that the officers in the United States Army who…are responsible for this willful, extravagant and outrageous waste of the taxpayers’ money, ought to be court-martialed and kicked out of the Army,” he declared.

Somervell was irritated, considering an attack on his methods to be tantamount to an attack on the United States. “I have been speculating, without being able to get an answer in my own mind, as to just what help these speeches are going to be to national defense,” he remarked to his staff the morning after the congressman’s speech. Engel, he told Groves, should be “very carefully watched” from then on.

Engel’s investigation made a big splash, but then died away. Especially after Pearl Harbor, Congress and the public were not in the mood to curb military spending. But by mid-1942, after the shock of war had worn off, Engel was quietly at it again, this time investigating the project being built right under his nose across the river from Washington.

The man on horseback

Somervell by then was reaching new heights of fame and notoriety. Since taking command of the Services of Supply in March 1942, he had created a vast global logistical empire and was now one of the most powerful figures in Washington. Rumors were circulating that summer that George Marshall would be sent to England as commander in chief of Allied forces and that Somervell would replace him as chief of staff of the Army. It was “brilliant, dashing” Somervell, wrote

Time

magazine, who “beyond all others in the Army except Douglas MacArthur has caught the public eye.”

Somervell’s rise inspired loathing from both sides of the political spectrum. The conservative radio commentator Fulton Lewis, Jr., railed against Somervell as a Roosevelt stooge and political appointee, describing him on the air as “a sort of personal protégé of that mystic figure who lives at the White House, Mr. Harry Hopkins.”

Roosevelt’s own liberal secretary of the interior did not entirely disagree. “There is more and more talk about Somervell supplanting Marshall and everyone seems to agree that he has the active backing of Harry Hopkins,” Harold Ickes wrote in his diary on June 21. The secretary, still aggrieved that the Pentagon was being built, was now smarting that Somervell had launched an astonishingly bold—and ultimately foolhardy—project to build an oil field, pipeline, and refinery for military use in uncharted mountainous terrain in Canada and had done it without so much as consulting the Interior Department, which was ostensibly in charge of oil concerns. Ickes seemed to believe Somervell was on the verge of launching a coup. “He gets things done but he is arbitrary and dictatorial—just the kind of a man who could become a danger in certain situations,” he wrote.

Lunching with Roosevelt at the White House several months later, Ickes warned the president that two Army generals were potential “men on horseback,” military strongmen who might seize power: MacArthur and Somervell. “He agreed as to MacArthur but said that he had not thought of Somervell,” Ickes recorded in his diary. “I told him that he would bear watching, pointing out that he was ambitious, ruthless and vindictive.” Roosevelt—more than likely to appease his volatile interior secretary—replied mildly that it would be “perfectly easy to shift a lieutenant general if necessary.”

Many in Washington “would gleefully have seen [Somervell] boiled in oil,” Roosevelt adviser Rexford Tugwell later wrote. “But he was just what Marshall needed, and so long as Marshall and the President were behind him he could not be reached.” Somervell occasionally needed to be “curbed,” Stimson later wrote, but his “driving energy was an enormous asset to the Army.” Those who accused Somervell of being an empire builder were absolutely right, but they missed a larger, more important truth—that the centralized and efficient empire he had established over mobilization, production, and supply of the U.S. Army would be absolutely critical in winning a global war.

Somervell was “one of the few Americans who really understand total war,” said Bernard Baruch, financier and adviser to many U.S. presidents. It was Somervell, perhaps more than any other leader, who made the case that America’s situation was desperate, and that sacrifice was required from all citizens. “We must face the truth, no matter how bitter the truth may be—we’re not winning the war,” he thundered in a speech in July to Detroit industrialists. To another audience in St. Louis he warned, “We’ve lost ships by the hundreds, men by the thousands. We’ve lost the freedom of the seas. We’ve lost everything except a smug sense of complacency. And that’s one thing we’ve got to lose, and lose fast, or we’ll lose our independence.” If American industry could out-produce the Axis, Somervell promised, “we’ll kick the living hell out of Hitler and the Japs.”

Somervell was driven by what one subordinate described as an “abiding sense of urgency,” one so compelling that he stopped signing his middle initial once the war broke out. The same techniques that had marked the Somervell Blitz in Army construction were now applied to logistics. Somervell declared war on what he called the Army’s “muzzle-loading” mentality. Officers who did not move fast enough were shuffled to obscure posts or forced into retirement. He fired or demoted more than a dozen generals “not to mention whole squads of colonels,”

Life

magazine noted.

“For cutting red tape and getting things done there had never been anyone like him,” Tugwell wrote.

A request for munitions was not paperwork to be pushed around on a desk, Somervell told his staff. “That is no piece of paper,” he said. “It is life or death, victory or defeat, for hundreds of our men in some stinking jungle.” With the Army in need of a good antitank weapon, Somervell went out to a range to observe a new shoulder-launched rocket-propelled weapon that had been fired only a few times and ordinarily would need much more development and testing before it was put in production. Somervell watched it fire and on the spot ordered ten thousand of them for the Army. “That damn thing looks just like Bob Burns’ bazooka,” an officer watching the demonstration remarked, referring to a popular radio comedian known for playing a crude wind instrument made out of gas pipes. The bazooka, as the weapon was soon also known, proved very effective in the hands of American soldiers.

None of it came cheaply. Somervell was going through phenomenal amounts of money—on weapons, on pipelines, on buildings—but complaints had been stifled since the outbreak of war. The muted response Somervell received in May when he belatedly notified the appropriations committees about the $14 million overrun at the Pentagon was typical. Renshaw marveled at Somervell’s ability to keep Congress in line, later describing the general’s methods: “Prominent members of the Appropriations Committee were invited to the Somervell home for a quiet evening of talk and a few drinks,” according to a summary of Renshaw’s remarks written by Army historians. “When the right glow of good fellowship was evident, he would casually mention a problem he was trying to solve and let it be known that the cost would probably be a little higher than had been anticipated. Things like this were difficult to estimate with dead accuracy. Thus, there was no shock when the bill reached them officially. Somervell liked it that way.”

The obstacle course

The glow of good fellowship was not going to work with Albert Engel, however. Groves would later say that Somervell had deceived Congress about the true cost of the Pentagon, and that this had provided good grounds for opponents such as Engel to attack him. Yet Groves himself was at least as guilty of deception.

In July 1942, Renshaw informed Groves that the Pentagon project had exceeded the $49 million figure Somervell had reported as the amended total cost for the project.

“And there’s no way to cover it up?” Groves asked Renshaw.

There was, though the idea Groves and his aides came up with was hardly foolproof. Lieutenant Colonel Gar Davidson, the former West Point football coach, telephoned Renshaw on the afternoon of July 10 with details of Groves’s plan. “He wanted the report on the building not to show any amount in excess of $49,250,000,” Davidson told Renshaw. “And then, he wanted a supplementary report on the roads and the parking area.”

“In other words, handle it like two projects,” Renshaw said.

“That’s the idea,” Davidson replied.

Never mind that Somervell had expressly promised Congress that his estimate would cover everything but parking. They would subtract the $8.6 million the War Department was paying for roads from the project total, and thereby keep the cost at $49 million. The only problem was Engel was hardly as stupid as Groves believed. (Groves later conceded that Engel “was stupid in a lot of ways but sharp in others.”)

Ironically, it had been Groves’s idea to bring Engel to the Pentagon in the first place. Groves had nothing but disdain for the congressman, considering Engel’s ballyhooed inspection tours “silly and at times almost idiotic.” Engel had been a consistent opponent of Construction Division projects on the House Appropriations Committee, yet Groves thought he could woo him with a personal tour of the Pentagon. “Groves had the idea he was going to make a friendly speech for us,” a rueful Renshaw later explained to another officer.

The congressman fancied himself an amateur builder, having recently borrowed some masonry books from the Library of Congress. When he was not on the road, Engel would get up at 4:30 in the morning and lay bricks for a six-foot-high wall around his house in suburban Washington, meticulously recording the number of bricks laid each day in a notebook he carried in his vest pocket. (The total had reached 14,391 by 1943.) To Groves, it was just proof that Engel was a dilettante who knew nothing about construction.

Groves’s strategy was to set up a construction playpen at the Pentagon and give Engel free run, figuring this would delight the congressman while wasting his energy. Before the tour, Groves directed McShain to put up an “obstacle course of scaffolding, plasterers and the like” in the area they would visit. When Groves brought Engel over to the Pentagon at 10

A.M.

on June 24, “I saw to it that he had everything to climb under and over that he could,” Groves later chortled. By 2

P.M.,

he returned to his office and left Engel to continue his visit. Groves was quite pleased with himself, thinking he had enlisted the congressman’s support.