The Pile of Stuff at the Bottom of the Stairs (15 page)

Read The Pile of Stuff at the Bottom of the Stairs Online

Authors: Christina Hopkinson

Tags: #FIC000000

“Gender politics. Not the top-level stuff about equal pay and quotas for board members or politicians, but more in the domestic sphere.” Somebody yawns. “I was reading the other day that even when a woman works outside the home, the amount of housework her partner does doesn’t increase. I’m sure there must be a way to explore this in a documentary, but in a fun way.”

“A fun look at housework?” asks Matt.

“I know, I know. But everybody does it, even if nobody talks about it. I thought you could take a variety of different household setups—single parent, working mother, non-working mother, house husband—and monitor what they think they do and what they actually do. Then we could question the participants to see if there was a direct correlation between marital satisfaction and equal participation in household chores. Even if there was a link between that and how much sex they have. There could be some tests common to all of them, like a mug left in the sink, how many minutes it stays there before the various different participants clean it or whether they notice it at all. I remember there was a documentary about sexual attraction once, where they had these cameras which could track the gaze of men and women, something like that. You could keep upping

the ante, with more and more extreme traps left for those men, or women, who never notice.”

“Yes,” says Lily, who has finally made it to the meeting fifteen minutes late, and whose presence I give silent thanks to for the enthusiasm that only she is expressing. “We could set up like this really gross reality house where it’s totally disgusting by the end and filled with really good-looking students.”

“

Big Brother

meets

How Clean Is Your House

? I like it,” says Matt. “Why don’t you try to flesh it out a bit, Lily, and we’ll think about pitching it to Factual Entertainment.”

“Hang on,” I say, “it was my idea. And it’s for Documentary.”

“We need you to coordinate the productions. You’re so good at it.”

“That’s like saying someone’s good at the washing-up.”

“You’re probably very good at that too.”

“I could do both. Developing the format and coordinating, I mean, not the washing-up. I can do a pitch based around a more serious approach to the subject.”

“Don’t think so,” says Matt. “What with all your time off and stuff.”

“It’s not time off. I’m part-time.” I’m sure you could be too, I think, if you’d sacrifice a large chunk of your salary and be prepared to answer calls and emails on your non-office day.

“Yes, that’s what I meant,” he says, dismissing both me and the meeting.

Valentine’s Day was never a golden date in my diary. Just a couple of weeks after my birthday, it only added to any lingering disappointment at the lack of cards/surfeit of obviously re-gifted gifts of my own anniversary. In my late teens I feigned a posture of antipathy, snarling that it was a tacky Hallmark invention of

the consumerist society. By my mid-twenties, this posture had calcified into authenticity.

Meeting Joel changed all that. The syrup of manufactured sentiment was made savory by a combination of my self-transforming love for him and his ability to find freshness in the most hackneyed of situations. I loved him so much that I allowed myself to be one half of a couple that mythologized its own specialness, the uniqueness of its love, and so was allowed to indulge in all manner of nauseating activities.

The first Valentine’s Day, he had a pliant café worker deliver to the office a be-ribboned latte, made with a double shot of espresso and soy milk, just the way I like it. He had decorated the mug himself, with Keith Haring–like doodles of hearts and flowers, using some specially bought ceramic paints. My boyfriend, I thought, is so artistic, so quirky, so cute, so in love with me and I with him. I kept the cup and used it only on special occasions, washing it gently afterward not with washing-up liquid but my own expensive handwash. It’s still in our crockery cupboard, only now the colors have long since faded, having been put through a dishwasher cycle one too many times.

The second Valentine’s Day, my true love made for me a treasure hunt that began with a clue attached to the collar of my flatmate’s cat and ended with a photo taken of us at the top of Ben Nevis, which he’d blown up to four foot by two foot proportions and managed to slip inside the front of the vending machine at the office. I was hugely embarrassed, of course, but since everyone there knew and adored Joel, I was secretly rather pleased too. Glad, at the same time, that we’d gone on holiday to chilly Scotland that year, not anywhere that might have involved the wearing of a bikini.

By the third Valentine’s Day the ante had been raised and

nothing less than a proposal would satisfy me. It was pathetic and I hated myself for it, but our relationship had started at such a fever pitch that I wanted to maintain this pace and excitement. Got a hand-knitted scarf with my initials embroidered into it. I tried not to be churlishly disappointed and felt silly when we did get engaged not long after, though in circumstances that fell short of the tales of romantic derring-do that I and others expected of Joel.

By the fourth Valentine’s Day we were married and I was pregnant. He still played the game, though, even now that he had me for life. He set up a dining table in the spare room of the first flat we owned together, blacked out the windows and turned off the lights. This was to re-create the ambience of a recently opened restaurant which offered the particular USP of serving food in pitch blackness. He then fed me a five-course meal that Heston Blumenthal would have been impressed by. To be honest, the experience of eating rich and complex food in total darkness made me feel rather nauseous, as well as worried about some of the oysters (that I had to spit out on account of being pregnant), getting ground into the new carpet. The meal culminated in a bout of frenzied sex and some weird stains on the paintwork that I was acutely conscious of when we had estate agents’ viewings.

The next few years blur into one another. The gestures were less dramatic, but there were still small surprises: Post-it note treasure hunts through the house; messages of love iced across fairy cakes; a first-edition book. Even last year, when we were well into our lives as stressed and stroppy parents of two, Joel hung up a banner painted with the help of the boys.

And now it is our ninth Valentine’s Day together. I’m scrubbing at the floor beneath the boys’ chairs.

He rips open a packet of Rice Krispies. I stop myself from pointing out that a) there’s a packet already open and b) why

doesn’t he cut the packet instead of ripping it, which would mean that it wouldn’t spill out over the work surface or accumulate at the bottom of the cardboard box and thus spill out when I collect up the cereal boxes to take to Rufus’s school for junk modeling. No, I breathe to myself, I shall just put these two points onto The List, which is safely stored on my laptop. And anyway, although Valentine’s Day is obviously a horrible consumerist construct, it is one that I will suspend animosity for. Or if I am feeling particularly generous, I may give him some get-out-of-jail-free passes to use against his miscreant behavior with dried breakfast products.

I continue watching him and then can bear it no longer.

“Do you know what day it is today?” I ask.

“Monday.”

“Yeah, but what day of the year it is?”

“Valentine’s Day.”

“Right, you do know,” I say.

“You don’t believe in Valentine’s Day, though, do you?” he says. “Or romance or flowers or in fact being very nice to your beloved, do you? Or even being civil to them and saying good morning?”

“Yes, obviously I think Valentine’s Day is silly. You’re the one who always makes such a big deal about it.”

He starts singing “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” and saunters off to the loo, leaving me with the post-breakfast, pre-departure flurry of bad tempers, missing nylon book bags and papier-mâché-like encrustations of Cheerios on the wall.

I spend the day pondering his elaborate subterfuge and wondering what surprise he will have planned for me that evening. One year, post-Rufus and pre-Gabe, he managed to organize babysitting for us to go out, despite the fact that all childcare was and is my provenance to the extent that he’d had to look on

my mobile to get the number of the babysitter. That he ended up phoning Maria my old school friend rather than Maria the nice Polish lady who looked after the baby occasionally was beside the point. And it was very kind of Maria my old school friend to come around to keep an eye on the baby monitor and watch our TV for a few hours, though as a City accountant, her rates were probably usually somewhat higher than our ₤6 per hour.

This intrigue sustains me through the day and I make myself up in honor of the surprised face I shall be making. I pick the kids up from Deena’s and I wait. And wait. Joel arrives back after their bedtime, one that has involved a three-way row between Rufus, Gabe and I, the kind of opposite of a group hug.

It’s now ten thirty and still I wait. For the first time in nine Valentine’s Days, the surprise is that there is no surprise. I open up my laptop in bed and add a few more things to The List.

“You do remember I’m off to book group this evening,” I say to Joel.

“But I’ve got to go out with everyone from work. Celebrate the commission.”

“I told you ages ago.”

“No, you didn’t.”

“Look, it’s on the calendar,” I say triumphantly and with some relief because until that moment of checking, I couldn’t have been entirely sure that it had been marked.

“Shit.”

“Don’t swear.”

“You don’t even like book group.”

True, I thought, there had been tears when somebody questioned another’s assertion that

The Time Traveler’s Wife

was the best book ever written.

“That’s not the point,” I say.

“What is the point, then?”

“The point is that you never respect my plans even if I’ve reserved going out first, which I did. It’s like my plans are secondary to yours, or like it’s my default role to look after the children so I have to get express permission to get out of it, while you can just automatically assume that I’ll be around to pick up the slack while off you go, gallivanting into the night. Even if it’s

a work thing I’ve got to do, it’s still secondary and I end up not doing it or I end up paying for the pleasure of working in the evenings, because childcare costs aren’t something we’re allowed to put on our expenses claims, while vast quantities of booze are.”

“Blimey, have you finished?”

“Yes.”

“Me going out is hardly likely to be fun. It’s work,” he says.

“Right, that trump card. Paper scissors stone, your work, my work, the children. Even when I’ve had a work thing to go to on the same night, I’ve always had to find a babysitter and pay for them, or cancel. Your work beats them all, doesn’t it?”

“Pays the mortgage.”

“And mine doesn’t? And remind me, how does going out for drinks after work pay the mortgage?”

“It’s important for morale.”

“That you get drunk?”

“Yes,” he says, very matter-of-factly. “I can’t be seen to be some sort of teetotal killjoy.”

“So what, when I don’t drink because I’m pregnant or breastfeeding or driving, I’m a teetotal killjoy, am I?”

“I didn’t say that.” He sighs. “Can’t you just get a babysitter?”

God, but he is feckless with money. The whole point of going out separately is that one of us stays at home so we don’t have to pay a babysitter. It is very aggravating to have to pay out all that money before you’ve even bought a drink. And I’m the one who has to ring around to get the babysitter—and I’m the one who pays them, too, as childcare’s one of my expenses, which is why he’s the one who can say that his work pays the mortgage.

What’s more annoying is that, while I don’t actively dislike book group, I don’t like it so much that I want to be shelling out ₤30 of babysitting money for the privilege of attending to the literary thoughts of Mitzi’s random assortment of mom friends.

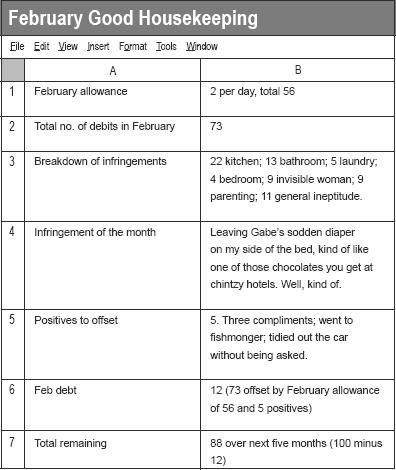

Breathe in, I tell myself. “Yes, all right, I’ll try to get a babysitter,” I say, while thinking with some glee about the huge accumulation of negative points for The List this short conversation has amassed. A point for not bothering to ask if it was fine that he goes out, a point for his going out trumping mine, a point for the fact that I pay for all the childcare, a point for his general uselessness with money.

“Thank you, darling.” He sounds surprised at my acquiescence. He gives me a kiss on my forehead in a patronizing style and skips off to work with nary a look back.

We are gathered at the home of Alison, who is Mitzi without the charm and humor. Or looks, charisma or generosity. In fact, she is Mitzi with a big bag of bitterness and resentment. So I guess, nothing like Mitzi at all, except that her house is fastidiously tidy, though lacking those dashing touches, those little stylish details, that save Mitzi’s from sterility. Alison is opining on the protagonist of this month’s book.

“She was such a whiner. I mean, she was so lucky to have a house with a proper garden.”