The Pillow Friend (43 page)

Authors: Lisa Tuttle

“Can you see anything? Can you see the baby?”

“My dear, you're barely dilated.”

“How long . . . ?”

“Hours yet. Tomorrow, maybe late tomorrow.”

She began to cry. “I can't. Not that long. I can't bear it.”

“My dear, you have to. There's no other way. Unless you want me to phone for an ambulance.”

“No! I'm staying here.”

Her breathing exercises did nothing for the pain, but they did give her something to focus on, something else besides the pain. When the contraction ended the pain vanished utterly, but she couldn't use the time, the minute or so in between the pain, for anything. She felt exhausted, desperate, with no resources to call on. Her mind wandered back to childhood, and she remembered the dream. It was the dream which had started it all, the dream which had implanted the desire in her which had led finally to this labor, this struggle which she began to believe would never end.

Yet for just a moment, remembering the dream, she seemed to reenter it, and was lifted above the pain as she felt again that miraculous, thrilling closeness, the happiness that the doll baby had inspired.

Other memories from childhood came flooding in, and she lost track of time and place, speaking to figures from her past as if they were still with her. It occurred to her that this birth she was struggling through was in fact her own—she was being reborn, and had to live through her own life again before she could move on to something new. Then she forgot that, and thought that Nancy was Leslie. Later, she was sure Roxanne was in the room. Then she realized it wasn't Roxanne. Someone else, another woman, was in the house with them.

“Who's here?” she asked.

“It's me,” said Nancy, at her side, wiping her face with a cool cloth.

“No, someone else—who is it?” She peered across the room, but her vision was blurred. “What happened to my glasses?”

“Do you want them? You asked me to take them off a little while ago.”

“I want to see who it is.”

“It's me, Nancy.”

“Not you, the other one.” She saw the figure of a woman approaching her, and for a moment thought she knew who it was. “But my mother's dead! I'm hallucinating.”

“It's all right,” said Nancy. “It happens; don't worry about it.”

“It's me,” said Marjorie. “Don't you know your own . . .”

“I thought you were dead! I thought you were my mother.”

“I'm not your mother. It's me.” And she held out her hand to be gripped just as another contraction made her cry out with pain.

She hadn't thought it possible for the pain to get worse, but it did. “Go ahead and scream,” said someone, she wasn't sure if it was Marjorie or Nancy. “There's no one here to mind. Make a noise, let it out. Push it out.”

“Go on, push,” said Nancy. She was on one side of her, Marjorie on the other, and they were lifting her up. “It's time now, it's coming. Bear down, hard as you can, push!”

She bore down so hard she knew she must be bursting veins, so hard she felt she would turn herself inside out, void her womb and everything else. Then, out of the hot, splitting pain, there was a cool, slippery sensation, and the pain and effort were abruptly over.

She lay still, her eyes closed, panting, relieved. It would be so easy to fall asleep just now, but something, an inner alarm, warned her not to rest, not yet. There was something wrong. The room was much too quiet.

She opened her eyes and saw Nancy. Without her glasses she could tell that Nancy was holding something, but not what it was. It seemed too small to be a baby, and it was dark, perhaps with blood.

“The baby,” she said. “Where is it? Let me see the baby.”

“There's no baby.”

“Then what are you holding? Come here, closer, where I can see—let me see—where are my glasses? What is that?”

“It's not a baby, it's a doll. A little, old-fashioned, porcelain doll. Not a baby, a man.”

“A doll?” Her heart leaped. “Myles? Bring it here, bring him here!”

Nancy came up beside her and handed her her glasses. “I'll make you a cup of tea.”

“No, wait—Myles, what happened to Myles?”

Nancy's face was sad and tired and puzzled. “Who?”

“The doll. You said—oh, just give him to me!”

“Agnes, you're hallucinating. You haven't had any sleep for days. You must rest. Lie down.”

“But the baby!”

“There is no baby. That may be hard to accept after what you've been through, but you've known it all along. You were the one who told me there would be no baby.”

“Maybe not a baby, but there was something, I pushed something out, and I saw you holding it.”

“There's nothing,” said Nancy, showing her empty hands.

“You have blood all over you.”

“Yes. You voided quite a lot of blood. Old menstrual blood, that's all you've been carrying. I'm going to get you a cup of tea and clean myself up and clean you up and then if you'd like something to help you sleep? Or maybe,” she said as Agnes sank back down, closing her eyes, “maybe you won't need anything.”

She struggled not to cry as Nancy walked away. It must be hormones making her feel so empty and bereft. She hadn't lost a child, she had lost nothing, there had never been a baby. She had known that all along, just as she'd known she didn't need or want a baby and all the responsibilities and problems it would bring with life as a single mother. But, still, she wanted something after all that, some resolution, her unspoken wish finally granted. What had she been struggling for these past two days, what had she been carrying inside her, besides the blood, these past nine months?

Sleep was pulling her down, unconsciousness waiting to claim her, when she was startled awake by a voice close to her ear saying her name.

She opened her eyes and saw Marjorie clearly for the first time. She was not her mother, she was herself, and she was holding a baby, small and naked and alive, its sex unclear.

She reached up to take it, and heard Marjorie say, “You know this baby is no more real than I am.”

“That's all right,” she said. She knew she must be dreaming, yet she felt it solid and warm and real in her hands. Why did people speak so dismissively of dreams, as if they were unimportant? She had been trying to find her way back to this dream for all of her waking life. “It's what I want. It's mine.”

The baby opened dark blue eyes and gazed with a sort of knowing wonder into her eyes. She felt a profound shock at the depth of their instant connection. And then the baby smiled at her, opening its mouth as if about to speak, and she knew she had everything she wanted.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LISA TUTTLE was born and raised in Houston, Texas, won the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer in 1974, and now lives with her husband and daughter on the west coast of Scotland. Her first novel,

Windhaven

,

was written with George R. R. Martin. Other novels include

Lost Futures

, which was short-listed for the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and

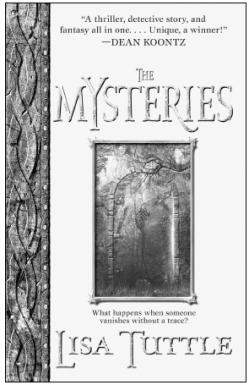

The Mysteries

.

ALSO BY LISA TUTTLE

Windhaven

(with George R. R. Martin)The Mysteries

Be sure not to miss

THE MYSTERIES

Another haunting, unforgettable novel by

LISA TUTTLE

Available now from Bantam Spectra

“

The Mysteries

is a thriller, detective story, and fantasy all in one—engaging, delightful, and wonderfully written. Unique, a winner!”—Dean Koontz

“Lisa Tuttle never disappoints.

The Mysteries

is a deft and daring blend of mystery and dark fantasy, about a private eye whose latest case leads him down the meanest street of all . . . the one to Faerie. Richly imagined and beautifully written, it lingers in the mind long after the last page is turned.”—George R. R. Martin

Here's a special preview:

THE MYSTERIES

on sale now

T

he strangest memory of my childhood concerns my father's disappearance.

This is what I remember:

It was late September. I was nine years old, and my sister Heather was seven and a half. Although summer was officially over and we'd been back at school for weeks, the weather continued warm and sunny, fall only the faintest suggestion in the turning of the leaves, and nothing to hint at the long Midwestern winter yet to come. Everybody knew this fine spell couldn't last, and so on Saturday morning my mother announced we were going to go for a picnic in the country.

My dad drove, as usual. As we left Milwaukee, the globe compass fixed to the dashboard—to me, an object of lasting affection—said we were heading north-northwest. I don't know how far we went. In those days, car journeys were always tedious and way too long. But this time, we stopped too soon. Dad pulled over to the side of a country road in the middle of nowhere. There was nothing but empty fields all around. I could see a farmhouse in the distance and some cows grazing in the next field over, but nothing else: no park, no woods, no beach, not even a picnic table.

“Are we here?” asked Heather, her voice a whine of disbelief.

“No, no, not yet,” said our mom, at the same moment as our dad said, “I have to see a man about a horse.”

“You mean

dog,

” Heather said. She giggled. “See a man about a dog, not a horse, silly.”

“This time, it might just be a horse,” he said, giving her a wink as he got out of the car.

“You kids stay where you are,” Mom said sharply. “He won't be long.”

My hand was already on the door handle, pressing down. “I have to go, too.”

She sighed. “Oh, all right. Not you, Heather. Stay.”

“Where's the bathroom?” Heather asked.

I was already out of the car and the door closed before I could hear her reply.

My father was only a few feet ahead of me, making his way slowly toward the field. He was in no hurry. He even paused and bent down to pick a flower.

A car was coming along the road from the other direction: I saw it glinting in the sun, though it was still far away. The land was surprisingly flat and open around here; a strange place to pick for a comfort stop, without even a tree to hide behind, and if my dad was really so desperate, that wasn't obvious from his leisurely pace. I trailed along behind, making no effort to catch up, eyes fixed on his familiar figure as he proceeded to walk into the field.

And then, all at once, he wasn't there.

I blinked and stared, then broke into a run toward the place where I'd last seen him. The only thing I could think of was that he'd fallen, or maybe even thrown himself, into some hidden ditch or hole. But there was no sign of him, or of any possible hiding place when I reached the spot where he'd vanished. The ground was level and unbroken, the grass came up no higher than my knees, and I could see in one terrified glance that I was the only person in the whole wide field.

Behind me, I heard shouting. Looking back, I saw that a second car had pulled off the road beside ours: an open-topped, shiny black antique. This was the car I'd noticed earlier coming along the road from the other direction. My mother had gotten out and was now in agitated conversation with a bearded man in a suit, a woman wearing a floppy hat, and two girls.

My mother called me. With a feeling of heavy dread in my stomach, I went back to the car. Heather was still in the backseat, oblivious to the drama. Seeing me approach, she pressed her face to the window, flattening her nose and distorting her face into a leering, piggy grin. I was too bewildered to respond.

“Where's your father, Ian?”

I shook my head and closed my eyes, hoping I would wake up. My mother caught hold of my arms and shook me slightly. “What happened? Where did he go? Ian, you must know! What did you see? Did he say anything? You were with him!”