The Plot on the Pyramid (6 page)

“Better than your best. Is that the best you can do?”

“It’s better,” Antef muttered. “May I get back to work now, your Majesty? They will be dropping that stone in place soon and I need to be there – we don’t want any more accidents.”

“Any more?” the King said. “Have there been any others?”

“No, your Majesty,” Antef said, a little confused. “Just the odd crushed beetle. Nothing to worry about.”

“Beetles?”

“Crushed.”

The King leaned forward and peered at the work-driver. “Are you all right, Antef?” Antef pulled out a large rag and covered his face with it.

“Sorry, Majesty,” he sniffled. “It was my favourite beetle.”

The King blew out his cheeks. “Antef. I think the sun has boiled your brain. Go home and rest until you feel better. Make one of the Boat Gang the new work-driver.”

“Yenini is very good, your majesty.”

“Very well, Yenini is the new work-driver,” he said and leaned back. “Servants! Take me back to the palace.”

The covered chair was carried away.

If the King had looked back he’d have seen Antef tear off the itching wig and the scratchy beard then run up the pyramid to where Yenini was waiting.

Antef ran with the stride of a gazelle and the padding fell out of his robes. He no longer looked like a fat little work-driver. He looked more like a girl called Nephoris hugging her father Yenini.

Maybe it was …

Nephoris walked home, arm in arm with her father, over the fields. She was carrying a purple robe, a perfumed wig and a beard wig. When they reached their village she handed them back to the artist Oneney and soon the fat statue of Antef was as good as new.

“I’m starving,” Yenini said. “With all that bother at the pyramid I didn’t even have time to eat my lunch.”

“Your dinner is ready now,” his wife said.

“No, it’s a pity to waste good food,” the man said. He pulled out his lunch packet and unwrapped it.

“Oh, Dad …” Nephoris began.

Too late. Yenini was staring at a fat, dead rat. He gave a roar that could be heard at the top of the pyramid. He threw the rat through the open doorway into the long grass with curses that would have frightened the demons of the underworld.

He was roaring so loudly he didn’t hear the little cry of fear from the grass where the rat had landed.

But little Pere’s sharp ears heard it. He pulled himself onto his stumpy legs and wandered out of the house. “Rats,” he muttered.

The stars were burning in the purple sky and a thin moon glittered on the inky Nile. Pere carefully pulled the grass apart and saw the man lying there. A short, fat, bald man. The dead rat was resting on his bald head where it had landed. He was quivering and too terrified to move it.

“Rats,” Pere said.

“Oh, little boy, hush. Don’t give me away. Spare me and I’ll see the King gives you a purse of gold. But don’t tell the men of Lisht I am here.”

“Little man,” Pere said.

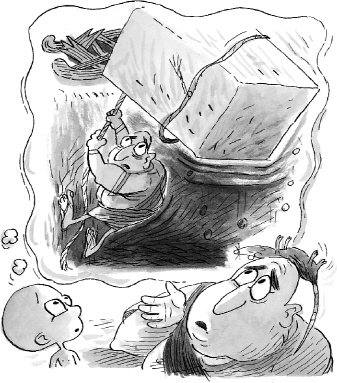

“They tried to kill me, you know. Left me in a hole and went to eat their lunch. I was lucky. I caught one of the ropes on the sledge and pulled myself up. But I was a bit too heavy. I pulled the stone down. It fell just after I scrambled out. Oh, but I ran down the other side of the pyramid. They didn’t see me. I bet they think they killed me!”

“Naughty man,” Pere said. He picked up the dead rat and slapped Antef across the head with it. It fell to the ground.

“I’ve taken off my wig and beard so no one will know me,” Antef babbled. “I’ve been hiding here all afternoon with the earwigs and spiders. When the moon sets I’ll go down to the port and take the next boat out of Lisht. And I’ll never come back. Never. They hate me.”

Pere giggled.

“But I am so hungry,” Antef groaned. “Can you give me something to eat, little boy? Please, please get me food – understand? Food. FOOD …”

Pere looked hard at the man with a face-crumpling frown. Then he smiled his one-toothed smile. He reached on to the ground and said, “Food!”

He picked up the rat and used his fat little fist to stuff it into Antef’s mouth.

The Egyptians worked hard to build the massive stone pyramids for their kings. They worked in groups and had names like “The Boat Gang”.

These men were paid in food, so building a pyramid wouldn’t make them rich. But they were proud to do this service for the king who was their god. They believed their king-god made the River Nile flood. This flood each year made sure their crops grew.

While the fields were flooded they were free to work on the pyramids. It seems some of the king’s officers treated the workers badly. They treated them like slaves and the proud peasants didn’t like that. In 1170 B.C. the workers organized what was the first ever strike.

The workers marched together into the temple, refusing to work. They complained about a lack of food and drink, clothing and medicine. A scribe wrote down their complaints. Their message finally reached the Pharaoh, who arranged for the men to be paid with corn. Strikes of this kind happened again during the reign of Ramses III and even later pharaohs.

There were many accidents on these dangerous building sites. Some might have been deliberate. “Oooops! Sorry I dropped that 20 ton block on your head, boss!”