The Ponder Heart (9 page)

Authors: Eudora Welty

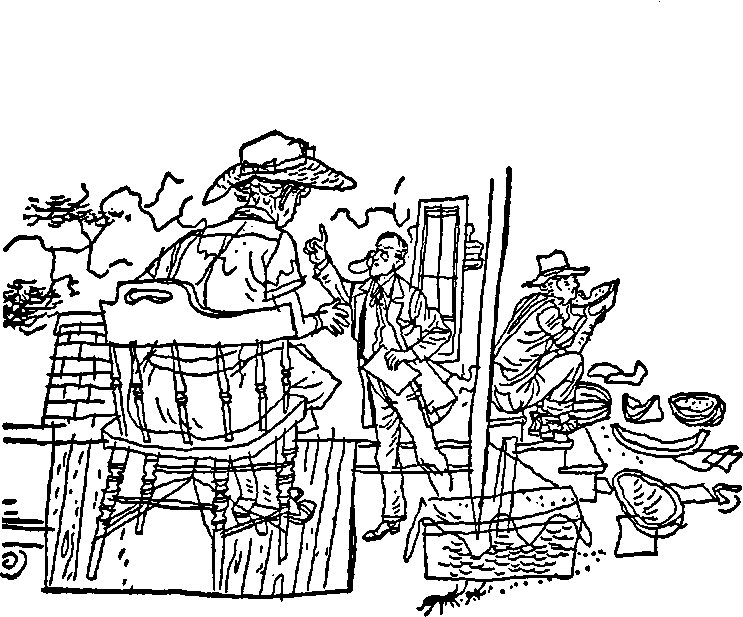

"Woman, were you working in the Ponder house on the day of which we speak, Monday afternoon the sixteenth of June?" says old Gladney.

"Just let me take off my shades," says Narciss. In town, she wears black glasses with white rims. She folds them in a case that's a celluloid butterfly, from Woolworth's, and says she was there Monday.

He asked her what she was doing the last thing she did for Mrs. Ponder, and when she got around to that answer, she said, "Draggin' old parlor sofa towards the middle of the room like she tole me."

"What for?"

"Sir, lightnin' was fixin to come in de windows. Gittin' out de way."

"Was Mrs. Ponder there in the parlor with you, woman?"

"She ridin' de sofa."

All the Peacocks laughed in court. They didn't mind hearing how lazy they were.

"Was Mrs. Ponder expecting company?"

"That's how come I ironed her apricots dress, all dem little pleats."

"And company came?"

Narciss looked around at me and slapped her leg.

"Who was it? Tell who you saw."

Narciss took him down by telling him she didn't see 5 but it was us. She ran out of the room first, but she had ears. They let her tell just what she heard, then.

Narciss said, "Hears de car Miss Edna Earle ride around in go umph, comin' to a stop by de tree. Hears Mr. Daniel's voice sound off in a happy-time way, sayin' Miss Bonnie Dee was sure right about de rain. Hears it rainin', lightnin' and thunderin', feets pacin' over de yard. And little dog barkin' at Miss Edna Earle 'cause she didn't bring him a sack of bones."

"So you could say who the company was," says old Gladney, and Narciss says, "Wasn't no spooks." But Judge Waite wouldn't let that count, either question or answer.

"Did Mrs. Ponder herself have a remark to make?" says old Gladney.

"Says, 'Here dey come. Glad to see

anybody.

If it gits anybody, hope it gits dem, not me.'"

Uncle Daniel turned around to me with his face all worked in an O. He always thought whatever Bonnie Dee opened her mouth and said was priceless. He recognized her from

that.

"Sh!" I said to him.

"Keep on," says old Gladney to Narciss.

"Can't keep on. I's gone by den."

"But you do know this much: at the time you left the parlor, and heard the company coming across the yard and talking, Mrs. Ponder was alive?"

Narciss gave him the most taking-down look she knows. "Alive as you is now."

"And when you saw Mrs. Ponder next?"

"Storm pass over," says Narciss, "I goes in de parlor and asks, 'Did I hear my name?' And dere Mr. Daniel and Miss Edna Earle holding together. And dere her, stretched out, all dem little pleats to do over, feets pointin' de other way round, and Dr. Lubanks snappin' down her eyes."

"Dead!" hollers Gladney, waving his hand like he had a flag in it. Uncle Daniel raised his eyes and kept watching that flag. "And don't that prove, Narciss, the company had something to do with it? Had everything to do with it! Mr. Daniel Ponder, like Othello of old, Narciss, he entered yonder and went to his lady's couch and he suffocated to death that beautiful, young, innocent, ninety-eight-pound bride of his, out of a fit of pure-D jealousy from the wellsprings of his aging heart."

Narciss's little dog was barking at him and DeYancey was objecting just as hard, but Narciss plain talks back to him.

"What's that you say, woman?" yells old Gladney, because he was through with her.

"Says naw sir. Don't know

he;

but Mr.

Daniel

didn't do nothin' like dat. His heart ain't grow old neither, by a long shot."

"What do you mean, old woman," yells old Gladney, and comes up and leans over her.

"Means you ain't brought up Mr. Daniel and I has. Find you somebody else," says Narciss.

Gladney says something about that's what the other side had better try to do. He says that's just what he means, there

wasn't

anybody elseâsince nobody would suspect Miss Edna Earle Ponder of anythingâbut he stamps away from Narciss like she'd just cheated him fine.

Up jumps De Yancey in his place, and says, "Narciss! At the time you heard company running across the yard, there was a storm breaking loose, was there not?"

"Yes

sir

."

"All right, tell meâwhat was the reason you only stayed to

hear

the company, not see them? Your best friends on earth! When they came in all wet and wanting to be brushed off, where were you?"

"Ho. I's in de back bedroom under de bed," says Narciss. "Miss Edna Earle's old room."

"Doing what?"

"

Hidin

'. I don't want to get no lightnin' bolts down me. Come lightnin' and thunder, Mr. DeYancey, you always going to find me clear back under de furthermost part of de bed in de furthermost back room. And ain't comin' out twell it's over."

"The same as ever," says DeYancey, and he smiles. "Now tell me this. What was Miss Bonnie Dee herself generally doing when there was such a thunderstorm?"

"Me and Miss Bonnie Dee, we generally gits down together. Us hides together under Miss Edna Earle's bed when it storms. Another thing we does together, Mr. De Yancey, I occasionally plays jacks with her," says Narciss, "soon as I gits my kitchen swep out."

And at first Bonnie Dee just couldn't stand Negroes! And I like her nerve, where she hid.

"But that Monday," says De Yancey, "that Monday, she didn't get down under anything?"

"She pleadin' company. So us just gits de sofa moved away from de lightnin' best we can. Ugh! I be's all by myself under de bedâlistenin' to

dat

" Narciss all at once dies laughing.

"So you can't know what happened right afterward?"

"Sir? I just be's tellin' you what happened," says Narciss. "Boom! Boom! Rackety rack!" Narciss laughs again and the little dog barks with her.

"Narciss! Open your eyes. Both of 'em." And DeYancey gave a whistle. Here came two little Bodkin boys, red as beets, wearing their Scout uniforms and dragging something together down the aisle.

"DeYancey, what is that thing?" asks Judge Waite from the bench.

"Just part of a tree," says DeYancey. He's a modest boy. I don't think it had been cut more than fifteen minutes. "You know what tree that is?" he says to Narciss.

"Know that fig tree other side of Jericho," says Narciss. "It's ours."

"Something specially big and loud

did

happen, Narciss, the minute after you ran under the bed, didn't it?"

DeYancey shakes the tree real soft and says,"Your Honor, I would like to enter as evidence the top four-foot section of the little-blue fig tree the Ponders have always had in their yard, known to all, standing about ten feet away from the chimney of the house, that was struck by a bolt of lightning on Monday afternoon, June the sixteenth, before the defendant and his niece had ever got in the house good. Had they gone in the side door, they would very likely not be with us now. In a moment I'll lay this before Your Honor and the jury. Please to pass it. Look at the lightning marks and the withered leaves, and pass it quietly to your neighbor. I submit that it was the racket this little-blue fig tree made being struck, and the blinding flash of it, just ten short feet from the walls of the Ponder house, that caused the heart of Mrs. Bonnie Dee Peacock Ponder to fail in her bosom.

This

is the racket you heard, Narciss. I told you to open your eyes."

Narciss opened her eyes and shut them again. It was the worst looking old piece of tree you ever saw. It looked like something had skinned down it with claws out. De Yancey switched it back and forth, sh! sh! under Narciss's nose and all at once she opened her mouth but not her eyes and said:

"Storm come closer and closer. Closer and closer, twell a big ball of fire come sidlin' down de air and hit right

yonder

â" she pointed without looking right under De Yancey's feet. "Ugh. You couldn't call it pretty. I feels it clackin' my teeths and twangin' my bones. Nippin' my heels. Den I couldn't no mo' hear and couldn't no mo' see, just smell dem smokes. Ugh. Den far away comes first little sound. It comes louder and louder twell it turn into little black dog whinin'âand pull me out from under de bed." She pointed at the dog without looking and he wagged his tail at her. Then Narciss opens her eyes and laughs, and shouts, "

Yassa! Bat

what git her!

You

hit it!" And all of a sudden she sets her glasses back on and quits her laughing and you can't see a thing more of her but stove black.

All I can say is, that was news to me.

"And

then

you heard the company at the door," says DeYancey, and they just nod at each other.

Old Gladney's right there and says, "Woman, are you prepared to swear on the Holy Scripture here that you know which one came in that house firstâthose white folks or that ball of fire?"

"

I

ain't got nothin' to do wid it," says Narciss, "which come in first. If white folks and ball of fire both tryin' git in you all's house, you best let

dem

mind who comin' in first.

I

ain't had nothin' to do wid it.

I

under de bed in Miss

Edna Earless

old room."

She just washed her hands of us. You can't count on them for a single minute. Old Gladney threw his hands in the air, but so did DeYancey.

"Come on, Sport," says Narciss, and she and Sport come on back up the aisle and stand at the back for the rest of it.

So about all old Gladney could do was holler a littleâI'll skip over thatâand say, "The prosecution rests." That looked like the best they could do, for the time being.

There was a kind of wait while DeYancey rattled his papers. I never knew what was on those. While he rattled, he had those little boys haul the fig tree around the room again, and up the aisle and back and forth in front of the jury, till Judge Waite made them quit and brush him off, and then they propped it up against the wall, in the corner across from the Confederate battle flag, where I reckon it still may be, with poor little figs no bigger than buttons still hanging on it. As Uncle Daniel said, we'll miss those.

The Peacocks were all looking around again. I don't know what they came expecting. Every once in a while, old man Peacock had been raising up from his seat and intoning, "Anybody here got a timepiece?" And Mrs. Peacock had settled into asking questions from the people behind her and across the aisle, about Clayâmostly about how many churches we had here and the like. To tell you the truth, Mrs. Peacock talked her way through that trial. If there was one second's wait between things,

she'd

say something. Once she says, "Anybody able to tell me what you can do about all this swelling?" and shows her fingers. "Wake up in the morning all right, and then, along towards now, I look like you'd chopped my fingers all off and stuck 'em back on again." She was right. But she wasn't spending the day in a doctor's waiting room. The Peacock girls sat with their arms tight around each other's necks like a picture-show partyâit was hard to tell where one left off and the other began. The littlest brother, about eight, walked up and down with a harmonica in his mouth, breathing through that. The babies kept sliding off laps and streaking for the door, and somebody had to run after them. And of course there was eternal jumping up for water from everybody, and a few water fightsâone right in the middle of Miss Teacake's spiel. It was hot, hot, hot. Judge Waite was heard to remark from the bench that this was the hottest weather ever to come within his jurisprudence.

Â

Finally, DeYancey got started and said that what he was undertaking to prove was that the Peacocks didn't have a case on earth. He said it would be very shortly seen that Bonnie Dee was beyond human aid already by the time Uncle Daniel and I put our foot over the sill of the door to that house. I laid my hand on Uncle Daniel's knee. He smiled at me just fine, because here came the blackberry lady, the ice man, and the blind man with the broomsâpeople he was glad to see again. They fell over each other testifying that Bonnie Dee had sent for Uncle Daniel. They just opened their mouths once and sat down.