The Portable Veblen (20 page)

Read The Portable Veblen Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mckenzie

nonrefundable,

with litter and junk mail for all!”

“Bill? Let’s not spoil the evening,” said Marion.

“Oh, no problem. I’m not the one selling my soul to Hutmacher Pharmaceuticals. Did you know in the paper today, they’ve just paid three billion dollars to settle a civil and criminal investigation?”

“Tell me something new!” Paul said. “You’re such a hick.”

“Dad’s a hick,” Justin said.

“Okay, Mr. Bigshot: three years ago, an executive at your sponsor, Hutmacher Pharmaceuticals, by the name of Leonard Byrd, filed a qui tam suit against the company—have you heard any of this?”

“Somehow I’ve missed it.”

“And I take it you know what that is?”

“A whistle-blower suit. Duh.”

“Yes. He revealed that the FDA was rubber-stamping Hutmacher’s toilet paper because of personal relationships between top management and high-level FDA and other government officials, and this is the part I want you to listen to, Paul. Paul, are you listening?”

Paul was draining his second glass of wine, and he brought his empty glass down on the table hard. He wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “I have no choice.”

“Here’s the part you need to know, Paul. Do you know what happened to Leonard Byrd?”

“Let’s guess. Veblen?”

“Um,” she said awkwardly. “He was found dead in a ditch?”

“Nobody knows. He’s

missing

. Vanished off the face of the earth.”

“Where did you hear this?” Paul asked.

“I found it. It’s been hushed up, you can only find snippets about it on the net.”

Thankfully at that moment the waitstaff surrounded them, and began to sing. They were offering up a piece of cheesecake hastily stabbed with a generic white candle, along with a blustery rendition of “Happy Birthday,” and other diners joined in, perhaps with real emotion because of Justin’s near-death experience. Applause followed the puff of Paul’s breath, which extinguished the teardrop flame.

Justin groped beneath the table and pulled up a gray cardboard tube.

“Paul. Happy birthday. You’re thirty-five.”

“Thanks.” Paul dismantled the tube, which yielded a knobby twig with bright-colored yarn tied on at various intervals. Bill and Marion watched expectantly, to add gravity to the gesture.

Justin worked a long time on this—react accordingly!

Paul smiled and looked at the stick, and Veblen hoped that he sincerely liked it. “This is great.”

“He looked for days for the right piece of wood.”

“It’s from the Japanese cherry,” said Bill. “Big limb came down in a storm.”

“We planted it when Paul was born,” Marion added.

“Cool,” Paul said. “So it comes with a lot of feeling.”

“Tell him what the knots signify,” Marion said.

“The knots are for your birthdays,” said Justin.

Paul looked. “Eight knots. Must be dog years.”

Justin laughed. Paul returned the stick to the tube.

“Here’s something for you.” Marion handed over an envelope.

“We thought you might like this better than some crapola you don’t need,” Bill said.

Paul opened the card. Veblen glimpsed a small wad of cash inside. Paul looked at it quickly then tamped it back.

“Thanks, Mom, Dad.”

“This is for Veblen.” Justin pulled up a small box, and she took it from him and opened it carefully.

“Oh, wow, thanks!” Inside was a small ingot, like an artifact from the Iron Age.

“I melted it and I made it,” said Justin. “And you know what it is?”

She gazed at its little curves and flourishes. “Is it a duck?”

“Yes!” cried Justin, with some drool.

For once, everyone at the table seemed happy.

“I love this,” she declared.

Bill and Marion looked on with evident gratitude.

“And here’s mine,” said Veblen, handing Paul her gift.

It was a picture of the two of them on the beach in Pescadero, framed. In essence, a picture of them beaming at a passing stranger.

“Were we smiling at her, or at us looking at ourselves in the future?” Veblen asked philosophically.

“At the great open maw of eternity,” Paul said.

“Let me see!” Justin cried, and grasped it with his greasy hands, and Paul left the table.

Back at the motel Justin stood by the rough gray trunk of the old oak in the parking lot, holding a golden acorn in his palm.

Just then a squirrel spiraled up the tree, leaping out to the end of a tapering limb. (Veblen wondered if squirrels were stirred when humans slowed to admire the nubby cupules, the voluptuous cotyledons, and the lustrous seed coat covering the pericarp, which indicated a peppery flavor. She had tried it.)

“That’s it,” said Justin.

“The one from the restaurant?” She peered closer, surprised to discern a certain sly wrinkle in its brow.

“MuuMuu,” Justin said, laughing.

Indeed, with the orderly rows of whiskers on its cheeks, the darkened follicles at the roots, the cascade of lashes on its brow, the cleanliness of its ears, the squirrel was unmistakable. “I think you’re right! How did it get over here?”

“Veblen, come in. Now!” Paul gestured from the door. What difference did it make if they stayed outside a moment more to watch a squirrel on this winter evening with their breath escaping in plumes?

“Look, you can see the squirrel’s breath,” she said, and Justin said, “I see the squirrel’s breath. I see it too!”

“Veblen?” called Paul.

“Want to see the squirrel’s breath?” called Veblen.

“NO, I DON’T WANT TO SEE THE SQUIRREL’S BREATH.”

“All right!” she said.

• • •

“P

AUL

? A

RE YOU OKAY

?”

It should be known that Veblen hated sharing events with people who didn’t enjoy them as much as she did. Nothing could bring

her down faster, or make her feel more acutely that an hour of her life had been forlorn. Maybe it was because anytime she and her mother attended a gathering in her youth, no matter how wonderful and festive it seemed, Melanie would scorch it afterward.

One time they attended a rockhounding fair in Santa Rosa. Veblen was jubilant. She had won a raffle at the door and picked a grab bag full of polished agates, seen glorious specimens of pyrite and amethyst, and met kids whose parents obviously had something in common with her mother, people her mother could not possibly object to, people they might form bonds with and see again. But in the car going home, Melanie said bitterly, “What a circus. Those nitwits have no concept of the environment. Did you hear that idiot talking about the way they stripped that hill of every last particle? What a horror show. Nobody there had our values.”

“They

do

like collecting rocks,” Veblen said, her voice rising. “That’s why we went there!”

“It’s not what I was expecting. Never again!”

Veblen let out a blood-curdling scream, enabling her mother to feel like the normal one.

They never found a soul with the same values. The moral fiber of others was always weak and frayed as far as her mother was concerned. Other people were insensitive and crass. Other people crashed through the world like barbarians, lacking manners, lacking taste, lacking sensitivity, lacking any regard for Melanie C. Duffy.

So when Paul’s mood did not match hers in the car driving home, she felt a painful flutter in her chest.

“What’s wrong?” she asked again.

His eyes darted in the dark. “How can I explain?”

“Well, try,” she coaxed, though she was having trouble hiding her distress.

“It’s just

them,

” he whispered.

“What did they do?”

“You didn’t notice?”

And she bit into her forearm so hard she almost cried out. Strife in the family she wanted to love wholly and fast was a catastrophe for Veblen.

“It’s just that Justin’s been trying to sabotage me since the day I was born,” Paul finally managed.

“How?”

“You don’t get it,” he growled. “See? I knew you wouldn’t.”

“But he’s disabled—how can he help it?” She bit her arm harder, steadying her jaw.

“Helen Keller was a spoiled brat until Anne Sullivan came along. My brother needs an Anne Sullivan, see what I’m saying? They’ve let him terrorize me all my life and never stopped him! You know what I realized tonight? He’ll probably sabotage the wedding. He won’t plan it, but he’ll erupt, he’ll act out, and why not, no one blames him for anything, there are no consequences, he’s free to do anything he wants.”

“But, Paul, don’t count on the worst. He couldn’t sabotage the wedding, it’s not possible!”

“You want to bet?”

Paul drove catatonically, a deeply wounded look in his eyes. “Veb, this thing against me, it’s all he’s got. So believe me, it’ll

happen, one way or another. It’s hard for me to feel like it doesn’t matter.” As if aware of Veblen’s resistance, he added, “I’ve been to counselors far and wide over this. He’s got my parents catering to his every whim, he doesn’t have to work or face the world, he gets their undivided attention and benefit of the doubt, and no matter what he does to me, I’m always the one in the wrong. I know it sounds paranoid, but it’s real. I’m sorry to drag you into my personal hell, but there it is.”

This is the price you have to pay

.

To be connected

.

“You’ve never mentioned this before,” she said, feeling betrayed.

“Look where he gets it,” Paul went on. “You heard my father. His digs about Hutmacher? It’s insane. He’s this close to being one of those guys who drive around in a van with a megaphone.”

“No, he’s not!”

“He did say I was a doctor. That was something. Remember in the restaurant?”

“Well you

are

.”

“To be healthy, I have to get rid of this baggage,” he admitted.

“It’s like a scar,” she offered, to cocoon the matter.

“It’s worse than a scar. I’m practically crippled.”

“Everybody has sore spots,” she whispered.

“Yep. Thank you for allowing me to have scars and sore spots.”

“Mmm,” she said, biting her arm higher up, where there was more flesh.

It would have been very helpful if Veblen could have been honest with herself at this point, if she had been able to admit that scars and sore spots terrified her, that she’d been helplessly driven

by someone’s scars and sore spots all her life, bleating like a lamb as the scars and sore spots nipped at her heels, sending her willy-nilly in directions she didn’t need to go, and that she’d wasted so much precious time that in the future she really, really didn’t want to be chased by any more scars and sore spots. But this she had yet to grasp.

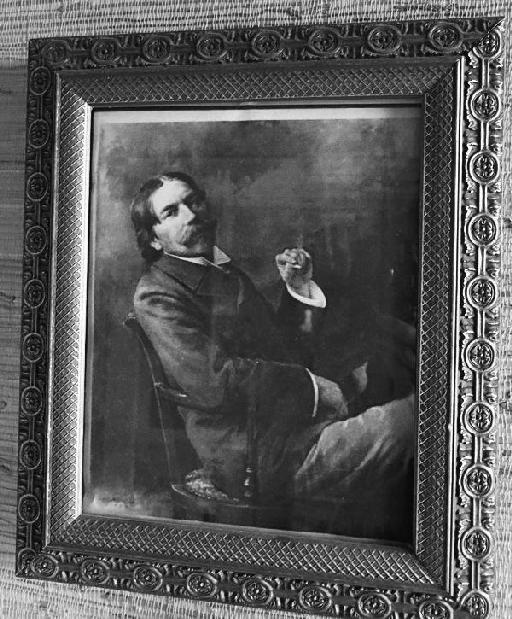

THORSTEIN VEBLEN, C. 1904.

Later she found herself catching her breath in the hallway, gazing at a mustachioed Norseman.

“Why are you always looking at him?” Paul said, irritably.

It was here, before Veblen’s portrait, that she came when she needed to find her best self, to remind herself there were many ways to achieve one’s ideals, not just the conventional ones.

“He makes me feel good,” Veblen said.

This appeared to further unsettle him, which she rather enjoyed, a cool slap on the buttock of assumption.

He plunked down on the edge of the bed, kicked off his shoes and socks. His shoulders sagged and his hair stuck out in spikes. Wait a minute, she loved him. She didn’t want to be mad about his attitude about his brother, or make him jealous of Thorstein Veblen.

“You make me feel better,” she added quickly.

Now Paul pulled the covers up under his chin. “You know they used to be nudists, don’t you?” he said.

“Who?”

“My family.”

“No! You never mentioned that.” She had noticed an endearing pattern: whenever Paul felt guilty or in need of affection, he’d tell a painful story about his past.

“Oh, yes. When I was in about fifth grade, for about a year or so. I’m telling you, I’m lucky I still have normal sexual feelings for women. Or anybody, for that matter.”

“Gee.”

“You’re in fifth grade and suddenly you start seeing your mother naked all the time? And your dad too? And your older brother? Sitting cross-legged on the floor? Walking around, leaning over, reaching for things in cupboards? Grotesque.”

She nodded with earnest sympathy. How many times had she borne witness to her naked mother, running to the bedroom after a shower with a towel pressed to her front? But repeated viewings of her mother’s unclad emotions had been way worse, and had led Veblen to fear depressives. Back then she’d run for cover outside, where she would help frightened grasshoppers escape into the ravine, in danger of her mother’s shears. (When she was in a bad mood, and even when she was in a good mood, Melanie liked to hunt them down and cut them cleanly in half, which made Veblen scream.) She’d pretend she was part of the resistance during World War II, helping grasshopper comrades escape across the border.

“So—that’s why you think squirrels are horrible?” she asked suddenly.

“Why?”

“Because they’re nude?”

He chuckled. “That’s it. Exactly.”