The Postcard (16 page)

I was amazed at how good she was. Her bright face was so innocent and believable.

“Yeah, in the morning,” I said. “Just after breakfast —”

“All right,” said the officer, heading for the door. “Believe it or not, we have crimes going on in this city right now. Son, expect another visit from Family Services. And please have your mother call me when she gets here.”

I said I would, and he left his number and extension and was gone.

“Man, you are awesome!” I said, stepping toward her, thinking twice, then stopping.

She pocketed the toothbrush and the razor. “You sounded in a bind. Plus, you look as pale as a pillowcase. A white one.”

“I almost forgot to tell you!” I said. “My house was broken into last night.”

“Holy —,” she said.

“It really spooked me out, but I’m not sure anything was taken.”

She glanced around. “How could you tell? Oh! Guess what else I found out? This is the best, best, best part. There was an article on the Ringling Web site written by guess who?” She stopped and smiled crazily at me.

“I don’t know.”

“Take a guess,” she said.

“I hate guessing.”

“Just guess,” she said.

“Fang.”

“Uh, no.”

“The red-bearded German guy?”

“Vis a translation? No.”

“Mr. Chalmers.”

“Ha!”

“Look, I don’t know —”

“Randy Halbert!”

I felt weak. “You’re not serious. Randy Halbert? The real estate guy?”

“In which he mentions guess who? Quincy Monroe, that’s who. They were friends, Monroe and the circus family. Well, not with Ringling so much, because he died in 1936, but the nephews and other people. Fang even stayed at their mansion when he wanted to get out of circulation for a while. Or, what I think, to hide Grandma Marnie!”

“Are you kidding me?”

“That’s what I said! The Oobarabs in the story are circus people, totally. Plus they are totally real and have been following us. Well, you. And why are they following us? Well, you? I’ll tell you. Because we’re getting close!”

“Yeah, but close to what?”

She nodded, grinning. “Exactly! Something very big. I’ll show you all the notes I took. I even downloaded a map of the Ringling estate. It took me forever. But not now; this afternoon. I have three lawns to mow before lunch. Maybe I’ll even get to finish yours. Your dad’s coming home soon, right? Why don’t you visit him ever?”

“Visit him! I’ve been busy!”

“He’s probably worried to death about you. You could at least call the poor guy, all busted up in there. Anyway, I’ll be back in two hours. Sooner, if I don’t have to rake.” She flew out of there like a bird, chirping all the way down the street to her house.

I was more confused than ever. Not about calling Dad — I knew I had to do that — but about everything else. For the next ten minutes I tried to sort it out, but things were happening too fast to put them in order. It was muddled. Oobarab. Baraboo. Circus. Real estate agents. Yellow socks. Daggers! Tigers! Ringling! Burglars!

Dad!

The kitchen phone rang. My ear was tired, and I was sick of this, but I thought it was Dia again so I answered.

“Dia?” said the voice. “Who’s Dia? Why is your cell phone forever going to voice mail? Jason, what’s going on down there?”

I sank to the floor. “Mom! Hi. Nothing. We’re cleaning up. Dad’s not here right now.”

“You’re

not

cleaning up,” she snapped. “And the hospital called me. Jason! A concussion? His leg broken? This is very serious. Why didn’t you tell me what was going on —”

“I’m fine. Dad’s fine.”

“He’s not fine! I’ve been crazy trying to reach you. I told the hospital if I wasn’t in London —”

“You’re in

London

? When did you get there?”

“I’m taking the first jet back.”

At that moment, I glanced over at the desk and saw the postcard that started it all, just sitting there flat. Man, all this mess from a little postcard —

I froze.

Wait. That’s not right. No, no. I grabbed for my backpack and pulled out two cards, one of Sunken Gardens, the other of the Hotel DeSoto.

What? What!

What was sitting on the desk? A new one? A

third

postcard? My heart began to batter my ribs again. I wanted to get to the card, but the phone cord wasn’t long enough. Holy, holy. “Holy —”

“What did you say?” asked my mother. “Jason?”

“Nothing, Mom. Sorry, my cell is ringing across the room. It’s probably the hospital. I think they want me to come. Dad’s supposed to get out today. I’m supposed to go there to meet him. At two . . . forty.”

“What?”

“I have to arrange for the taxi and stuff.”

“Don’t they have people to do that for you?”

“They do. That’s right. That’s what they said. We’re pretty good right now. I’ve been staying with Mrs. K next door.”

“Who? Mrs. Kay?”

“A friend of Grandma’s,” I said. “And also I’ve been eating dinner with a really a nice family. I’ve been cleaning the place up, and the real estate agent is probably bringing people in the morning, the first people to look at it. You don’t have to come down here. I mean, you could, sure, but you don’t have to right away —”

“Oh, I’m coming,” she said. “The meetings aren’t over until tomorrow late. In the meantime, your sister’s on her way. This is so incredible. Jason, I can’t believe you didn’t call.”

“Becca’s coming?” I said. “When?”

“Tomorrow. Monday, I mean. It’s Ray-Ray’s birthday tomorrow.” She sighed. “How much did he drink?”

“It was mostly an accident, Mom. He just fell. It was a lousy ladder. You know, Grandma wasn’t into the best tools and stuff.”

“Don’t give me that. The doctor told me it was probably three or four beers. Thank God he wasn’t driving you. Your poor father. I have to come. I just have to.”

There was a silence next that dragged on a bit.

“Mom?”

“I’m here,” she said.

“Mom. I’ll have Dad call you. I’m going to talk to him soon.”

More quiet on the line, then, “Call earlier rather than later. We’re six hours later. Five. Whatever. Call me. I’ll come as soon as I can. Expect Becca on Monday.”

There were a few more words, but I couldn’t tell you what. As soon as I was off the phone, I jumped across the room and snatched up the postcard.

Last night’s intruder had left it. Of course, he did. Was it another clue? Who the heck would break into my house and leave this? A friend? An enemy? An . . . Oobarab?

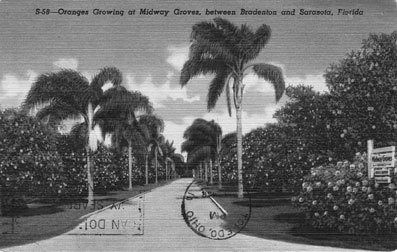

The card showed what looked like an enormous European castle, floating like an island in bright blue water. The castle had red tile roofs, dozens of arched windows, balconies everywhere, and fancy designs in the stones. I flipped the card over, hoping what it would say, but still stunned to read the words.

John Ringling Mansion Sarasota, Florida

My knees turned to jelly. There was no address or postmark. All that was there, in clear marks made by a ballpoint pen, was this:

IV

Okay. Okay. Turning back to the picture, I lifted the card to the light, slowly, slowly. And there it was, a tiny twinkle of light near the top of the castle’s tower, just under the tiled roof.

This was it.

I shook and shook and finally managed to call Dia again.

“Look, Barton,” she said when her mother called her to the phone, “do you think I just pine around hoping you’ll call? I was putting gas in the mower. For crying out loud, what is it?”

“I told you someone broke in here last night. I thought nothing was taken. And nothing was. But they left something behind.”

She got quiet on the other end. “Not a . . . postcard?”

“Sarasota,” I said. “The Ringling Mansion.”

There was a scuffling sound like hands over the receiver for a few seconds. When she spoke again, she said, “I’m on my way.”

The Ringling mansion was called

Ca d’Zan.

Dia said her father pronounced it: kah-dah-

zahn.

We suspected that going to Sarasota might be a trap — we were being lured there, after all — but there was nothing we could do about it. We had to follow the trail. Even so, we could use all the information we could possibly get. And Dia knew just where to go.

“Randy Halbert’s office,” she said.

“You know,” I told her on the bus there, “you get everybody else’s name right. Why not mine?”

She turned to me with a puzzled look on her face. “Wait, you have a name?”

“I wonder.”

She smirked. “I wonder if you wonder.”

I couldn’t even tell you what that meant.

It was Sunday, but his office was open. As usual, when we pulled on the door, the air conditioning practically blew us back out onto the street again. His secretary sat alone at her computer, looking sour and sipping a foamy iced coffee from a domed plastic container. She said: “I’m sorry, it’s Mr. Halbert’s day off.” Then she laughed a weird little laugh and said that real estate agents didn’t have days off, so she wrote down where he lived. “Take a number fourteen and get off in Gulfport,” she said. “He’s a couple of blocks before Stetson U. Remember to say hi for me.” She sipped her iced coffee, then added, “Nah, don’t remember.”

We took the bus, walked to 52nd Street, and found Randy Halbert’s house. It was a small light blue box, well-trimmed and neat, with a new tile roof. We went up to the front door and rang the bell. A low-tide breeze wafted over us. The door creaked open.

“Is Randy —,” Dia said.

“Shhh!” said a voice near her knees. A man on all fours was bent over the floor behind the door.

“Excuse me, do you need help getting up?” I asked.

“Hold on!” he grumbled, nudging the door closed with his shoulder.

We heard all kinds of shoving and scraping sounds. Finally the door swung wide. We faced a little old bald man with a dustrag rubber-banded over his nose and mouth like a bandanna. He looked like a bank robber, except for the reading glasses that gave him giant fish eyes.

“You want Randy,” he whispered behind the cloth. “He’s in there. And shhh.” He gave a nod to the right.

“Thanks —,” I started.

“I said,

shhh

!”

Giving each other a look, Dia and I stepped onto a large sheet of cardboard placed over the floor, which looked as if it were being retiled. We tiptoed into the Florida room. Randy Halbert was sitting on his couch amid a bunch of magazines, flipping through one of them. He looked up, but not quite at us, when we walked in.

“Jeez, kids. This is my day off. What are you doing here?”

Dia and I hadn’t really discussed about how much to tell him, but I felt we were getting close to something, so I told him pretty much everything — my grandmother, her boyfriend Emerson, the postcards, the Awnings, the Towers, the whole wild story. Finally I said that we knew about his interest in the Ringling house.

“Ten minutes,” he said in a sulky sort of way to our waists. Then he waved his hand toward a pair of chairs, and we sat across from him. “I have to say, I’m kind of impressed,” he said. “Not everyone makes connections between all the things you’re talking about. So which one of you is the detective?”

“I am,” we chimed together.

“Try to keep it down,” he said in a hush. “Whisper, please.”

Dia tensed up and scanned the rooms beyond us. “Why whisper? Is someone here? Is it Fang? Blink twice if it is!”

He didn’t even blink once. “I’m babysitting my granddaughter. She’s napping.”

I got right to the point. “I need to know anything you can tell me about Quincy Monroe and my grandmother and any connection to the big Ringling house.”

The agent glanced over at the old man, who was on his knees again scraping and tapping on the floor. When we heard the baby cry from another room, the man got up, and Randy frowned as if he were annoyed, then resigned to telling us what he knew. I think he wanted us to leave as soon as possible.

“The Monroe family,” he said, “was one of the first great families of Florida’s west coast. Boosters, they used to call people like the Monroes. The early land booms brought all kinds of people here. The Gulf Coast Railway was founded by Patterson Monroe and taken over by his son Quincy when he died. They scooped up land wherever they could find it. The Monroe Dynasty, they called it. Soon they were not only railroad barons, but had gotten into hotels, citrus plantations, residential housing. You following?” he said to my T-shirt.

We both nodded.

“This is Florida,” he went on. “Finally it’s all about land and Quincy had plenty of it, downtown, up and down the coast, what have you. When the first land boom ended in 1926 and the stock market crashed three years later, and the Depression came, landowners were caught like everyone else. Monroe was one of the few buying. He made shady deals, under the table, things that might be thought of nowadays as swindles, even hoodwinked the state, so they say. Florida was wide open and wild back then. What others had to sell to survive, he siphoned off cheap. It made him a lot of enemies. A scandal blossomed in 1933, I think. I want to say big scandal, but nothing happened. It was investigated, then went away. I think Monroe pulled a blanket over the whole thing. No proof. It was the kind of power he had.”

I wondered about that. Was that why Nick’s father wanted the newspaper that day? To find out about what happened in the state capital? That was about land and money. Nick remembered that that was back when he was nine. Maybe that was in 1933.

“Go on,” I said.

“Ringling died a few years later,” he said.

“In 1936, I read,” said Dia.

Randy nodded. “There was a distant relative, a hanger-on, who stayed friends with Monroe. When the mansion,

Ca d’Zan,

opened to the public in 1946, this nephew kept his hand in close. He had parties there. Even lived there for a time during the off-seasons. Monroe and his family were visitors.”

The old man, still wearing the dust rag over his mouth, leaned into the room. “Emma fell back asleep in my arms,” he said. “She’ll be in dreamland for a good hour.”

Randy snickered. “Didn’t Great-grandpa’s mask scare her?”

“It takes a lot to scare that little girl,” he said with a sound like chuckling. “I’m gonna trim the hedge.”

“Wear your hat. It’s sunny out there,” said Randy.

“Never leave home without it,” he chirped. A second later, we heard the front door click.

“What about Emerson Beale and my grandmother?” I asked.

Randy shifted on the couch. “I know he was her boyfriend, but her old man didn’t like him. Why is anyone’s guess. Tried to shoo him away. After the accident in that crazy, experimental autogyro thingy, which Monroe blamed himself for since he was driving it, his vast empire began to crumble. He sold off pieces of it to pay for doctors, unorthodox treatments, procedures, going to clinics all over the world so that his daughter might walk again. He tried it all, gave her anything and everything —”

“Except what she really wanted,” said Dia. “Nick Falcon.”

“Emerson Beale,” I said.

Randy shrugged, his eyes flicking nearly to my face, then away. “She was married to a man named Walter Huff. But he died overseas, they say. They had a son — your father — but who knows how she took care of him. The old man wasn’t crazy about that, either. I get the impression she really loved your father as best she could, but she was so ill, disabled after the accident, and Monroe kept sending him off to schools and things. I can’t imagine what that must have been like, but he’s probably told you that already.”

Dad hadn’t told anyone, of course, not the whole story. Mom knew about Walter Huff being only a name, and she suspected Fracker of something not quite right, but that was only part of it. There were Dad’s years as a boy living day after day with a sick mother and a cold grandfather. That was part of what he kept inside. That was the reason he was the way he was. It was so odd, and sad, hearing this from a stranger.

The room went quiet for a while.

Dia showed Randy the postcard of the Ringling house, and he smiled. “These postcards. Sometimes you can see buildings, places that don’t exist anymore except on one of these cards.”

He chuckled to himself in his usual way. “The strange thing I’ve noticed is how if you look at these cards long enough, the real world begins to take on these colors. The grass, the cars, the buildings. It’s like the artificial becomes real. As for the Ringling estate,” he said, handing the card back, “it’s still there, and it’s still like that. It’s an attraction now, but I’ve been on the grounds of the estate when everyone leaves, and it’s something you’ll never believe. The whole

now

falls away when you’re at that house. Old Florida comes alive out of the air.”

Something I wanted to say then but just couldn’t bring myself to, Dia blurted out. “But you’re helping to tear down old Florida. The hotel, for one thing. And your luxury mall? The DeSoto Galleria? Are you kidding?”

He breathed in. “Right. I know,” he said slowly. “The truth is, we don’t live in the past. We can’t. But you can love parts of it. And you pick and choose. This house, the house my wife grew up in, my father-in-law’s house to begin with, she loved it. If you can believe it, it was originally built in one of Monroe’s developments for his railroad workers. Nineteen-twenty-eight. We’re restoring it to the way it was. Spanish style. Sarah’s dad’s helping me, as you see. And the mall will use fixtures from the old hotel, the columns, the woodwork. Which I made sure of. You pick and choose. And do your best.”

Randy Halbert was looking at us now. “The best of it, of old Florida,” he said, nodding at the postcard in my hand, “is in a place like that. It’s so . . . beautiful.”

Dia stood. “We want to go there. We need to go there.”

He nodded. “I’d even take you, but my wife’s out and my granddaughter . . .”

“That’s okay,” I said. “Thanks for your help.”

“Watch out for yourselves,” he said.

“Which reminds me,” said Dia when we got up. “What exactly is the Secret Order of Oobarab?”

He snickered. “It was a group of circus folk who claimed to be the descendants of the real first circus from Baraboo, Wisconsin,” he said. “Most of them never made John Ringling’s cut. But they hung around and were perfect for Monroe. To do his dark dealings. If any of its members are still alive, they must be quite ancient by now. The Order must have long since disbanded.”

“Not so much,” said Dia. “The Oobarabs are back. Jimbo and I have seen them.”

Randy frowned at our knees. “Who’s Jimbo?”

“Me,” I said.