The Power of Mindful Learning (15 page)

Read The Power of Mindful Learning Online

Authors: Ellen J. Langer

In the three cultures (mainland Chinese, American Deaf,

and hearing American) we measured the following three

hypotheses: (1) The Chinese and hearing-impaired American

cultures hold more positive views of aging than does the hearing mainstream American culture. (2) Young subjects in each

culture perform similarly on the memory tests, whereas the

elder Chinese and American Deaf participants outperform the

elder hearing American group. (3) There is a relationship

between positive views toward aging and better memory performance found among the older subjects.

We selected thirty participants from each culture. Half the

members of these three groups consisted of young adults (aged

15 to 30 years; mean = 22 years), and half consisted of elderly

adults (aged 59 to 91 years; mean = 70 years). We selected fiftynine years as the starting age for the old group because in

China, most women retire by the age of fifty-five and most

men retire at the age of sixty;23 in addition, age fifty-nine is

about when people in the hearing-impaired community begin

to attend social events planned for older adults.24 We matched

subjects in the three cultures by years of education, socioeconomic status, and age.

In the United States, experimenters recruited all participants from the Boston area. We recruited the fifteen younger

hearing individuals from youth organizations and the fifteen

older hearing participants from a senior drop-in center. We

recruited the fifteen younger Deaf individuals from a Deaf cultural organization and the fifteen Deaf elderly from a senior

drop-in center. In China, interviewers recruited the thirty sub jects from a pencil factory located in the western district of

Beijing. The fifteen younger subjects were currently working at

the pencil factory, and the fifteen older subjects returned to the

factory once a month to collect their pension checks.

To test memory, we showed subjects photos of elderly individuals whom they were told they would one day meet. For the

hearing sample, each photo was presented for five seconds, the

experimenter read a passage about an activity involving the photographed person (e.g., swimming every day), and then the subject examined the photo again. In the hearing-impaired sample,

the statement about the activity was signed. For the Chinese

groups, the photos were of elderly Chinese. All subjects were

then shown the photos and asked to give us the matched activity.

The three groups of young subjects performed similarly on

the memory task, as we had predicted. The elder Deaf and

elder Chinese participants clearly outperformed the elder hearing group. There was no difference in memory performance

between the two Chinese age groups.

We also rated the views toward aging in these three cultures

by having subjects in each group answer the question, "What are

the first five words or descriptions that come to mind when

thinking of somebody old?" Answers were evaluated for positivity by raters who were unaware of the culture or age of the subject. We found that these views correlated with the performance

of the three groups, that is, negative views correlated with poorer

performance in the older groups. These results support the view

that cultural beliefs about aging play a role in determining the

degree of memory loss that people experience in old age.

The rigid mindsets we hold about ourselves affect our performance. These mindsets, including our beliefs about old age,

are often unwittingly accepted at a time when they may seem

irrelevant to our current concerns. Children who do not care

about school may accept negative assessments of their abilities.

Later, when they come to care about the particular abilities in

question, these assessments are already fixed in their minds. At

that point the damage is done. The mindset does not get

tested; it is treated as though it is necessarily true. This may be

how we accept the so-called inevitable memory decline with

age. If we are led to believe that we have poor memories or that

we are poor students, these mindsets can become self-fulfilling

prophecies.

The negative assumption about mental capacity in old age

can be seen in many adult education courses. Although there is

no reason to believe that information imparted to older people

should differ from that taught in colleges, catalogs aimed at

older adults are filled with far more narrow topics. They typically deal with retirement and health issues or with lightweight

courses in appreciating art or music. The experience of younger

people in college courses may be shortchanged by the absence of

older adults. Older adults are more likely to have had experiences that tell us that the new facts being imparted are more

true in some contexts than in others. Diversity provokes mindfulness. Their more extensive and varied experiences may reveal

the meaningfulness of certain information that would otherwise

appear irrelevant. Not only is education not wasted on the old

but, without their participation, it may be wasted on the young.

A man who lived on the northern frontier of

China was skilled in interpreting events. One

day, for no reason, his horse ran away to the

nomads across the border. Everyone tried to console him, but his father said, "What makes you so

sure this isn't a blessing?" Some months later his

horse returned, bringing a splendid nomad stallion. Everyone congratulated him, but his father

said, "What makes you so sure this isn't a disaster?" Their household was richer by a fine horse,

which his son loved to ride. One day he fell and

broke his hip. Everyone tried to console him, but

his father said, "What makes you so sure this isn't

a blessing?"

A year later the nomads came in force across the border, and

every able-bodied man took his bow and went into battle. The Chinese frontiersmen lost nine of every ten men. Only because the son

was lame did the father and son survive to take care of each other. Truly, blessing turns to disaster, and disaster to blessing: the changes

have no end, nor can the mystery be fathomed.

The Lost Horse

CHINESE FOLKTALE

The very notion of intelligence may be clouded by a myth:

the belief that being intelligent means knowing what is out

there. Many theories of intelligence assume that there is an

absolute reality out there, and the more intelligent the person,

the greater his or her awareness of this reality. Great intelligence, in this view, implies an optimal fit between individual

and environment. An alternative view, which is at the base of

mindfulness research, is that individuals may always define

their relation to their environment in several ways, essentially

creating the reality that is out there. What is out there is

shaped by how we view it.

Despite the emphasis in current intelligence theory on several kinds of intelligence, there is still an assumption of an

absolute, external reality revealed by greater or lesser degrees of

these various sorts of intelligence. This assumption is of more

than academic interest; it may have detrimental effects on selfperception, perception of others, personal control, and the educational process itself.

As we will see in this chapter, belief that one's perceptions

must correspond to the environment and that the level of correspondence is a measure of intelligence stems from a nineteenth-century view but continues to be influential today. A theory of correspondence between cognitive faculties and

environment can be found in a variety of concepts of intelligence, ranging from Charles Spearman'sl "g," a general factor

that describes the correlation among many cognitive abilities,

to Howard Gardner's2 multiple intelligences, which are any

socially valued abilities. The assessment of each ability depends on an assumption of a certain reality; the intelligence in

question corresponds to that reality. For instance, the currently

popular notion of emotional intelligence implies that certain

people have a keener sense than others of what other people

are actually thinking and feeling? Research that my colleagues

and I have conducted has shown how this theory of correspondence can be intellectually, emotionally, and physically

debilitating.

Before discussing the damaging effects of such a view, it

may be helpful to look for its source by tracing the roots of

intelligence theory back to the nineteenth century.

In 1854, Hermann von Helmholtz observed a curious phenomenon. When he looked with each eye on a different-colored square-a red square for one eye and a green square for

the other, with a divider separating the two-he was able to

bring only one square into focus at a time; also, his attention

tended to drift from one color to the other.' His inability to

control what part of his perceptual world came into focus and his failure to bring these two pieces-these small squares-of

experience together in a unified visual field led Helmholtz to

extensive speculation and empirical research about the ways in

which we make sense of our environment.

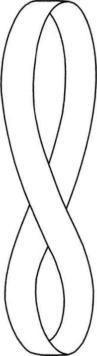

Our inability to attend to both of Helmholtz's images

simultaneously-a phenomenon that has been frequently replicated-raises this question: If only one image can be within our

perceptual field at a time and we cannot directly perceive the

relation between these images, why do we automatically form a

conception of their relationship? There are two approaches to

answering this question. For many theorists of intelligence, the

question is primarily epistemological: "How can I know what

relationships exist among the pieces of my experience if I do

not perceive the relations directly?" From the point of view of

mindfulness theory, this question is primarily an issue of personal control: "Is my way of perceiving the relationships among

the pieces of my experience so automatic that it is beyond my

control?" The deliberately ambiguous image in Figure 1 may

make these questions more concrete.