The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (4 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

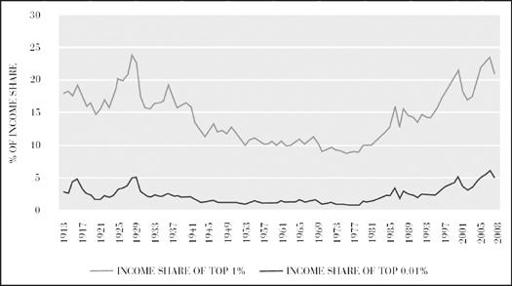

Figure 2.7: Rising Income Inequality, 1913–2008

Source: Data from Database for “Income Inequality in the United States” (Saez and Piketty).

Soaring income and power at the top has changed American society. Many of those at the top of the heap have come to look upon the rest of society with disdain. We have entered an age of impunity, in which rich and powerful members of society—CEOs, financial managers, and their friends in high political office—seem often to view themselves as above the law.

The recent cascade of corporate scandals has been unrelenting, often with close links between the scandal-ridden companies and powerful politicians. Dick Cheney went from being the CEO of Halliburton, a company involved in an endless tangle of bribery, contract violations, accounting frauds, and safety violations, straight to the vice presidency, where he used his high public office to coddle the oil industry. And Wall Street firms such as Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and JPMorgan Chase not only were the central actors in the financial crisis of 2008 but were the very places to which Obama turned to staff the senior economic posts of his administration.

It’s hard to know the ultimate cause of the breakdown in corporate truth telling and ethical business behavior in general. Dishonesty is a contagious social disease; once it gets started, it tends to spread.

23

Our “social immune system” has been deeply compromised. Perhaps we’ve become inured to hucksterism through a lifetime of watching the phony claims of advertisements, campaign commercials, and official military statements on Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Perhaps the cause is the parade of CEOs who have cheated their own companies, their shareholders, and their customers, giving us the

sense that everybody in corporate America is cheating. Perhaps the cause has been the repeated exposés of corporate lies in the drug and oil industries, financial rating agencies, investment banks, and military contractors.

When something goes wrong—a drug proves dangerous in follow-up tests, a drilling practice proves hazardous, or a paramilitary unit engages in murder or torture—the inevitable response is to lie first, cover up next, and acknowledge the truth only as a last resort, usually when internal documents are finally leaked to the public. I witnessed this at Harvard as well, when the U.S. government charged a colleague of mine with insider dealing on a federal contract. The university’s response was to mobilize the PR machinery and fight the charges rather than to search for the truth.

Perhaps the ultimate cause is the nearly complete impunity of lying or costly failures in leadership. Almost nobody at the top pays a price for such behavior, even when the truth is eventually exposed. The bankers who brought down the world economy remain at the top of the heap, sitting across the table from the president in White House meetings or dining at state dinners as the president’s guests of honor. Policy advisers such as Larry Summers, who led the U.S. government to deregulate the financial markets in the late 1990s, have been rewarded with lucrative positions on Wall Street and academia and then with renewed appointments at the top of government.

Those who are actually found guilty of violating the law typically get off with a slap on the wrist, if that. When Goldman Sachs was charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with stoking the subprime bubble through marketing of toxic securities under phony premises, the SEC agreed to a settlement of $550 million, a pittance compared to the firm’s $13.4 billion income in 2009. When another creator of the subprime disaster, Countrywide Financial CEO Angelo Mozilo, was sentenced for fraud, the fine was $67.5 million, seemingly hefty until compared with Mozilo’s 2001–2006 compensation, estimated at $470 million. The list is long. Wall

Street has acknowledged wrongdoing in one case after another, only to walk away with mild fines.

24

Retracing Our Steps

America’s problems may seem insoluble today, but that’s mainly because the United States has gotten out of the practice of true social reform and problem solving. Once we start to diagnose our real ills and chart a course to solve them, practical problem solving will prove to be realistic after all. Despite all the challenges—budget deficits, financial scandals, lack of proper public education, corporate lying, impunity, antiscientific propaganda, and more—the U.S. economy remains highly productive and innovative. Even with the steep downturn after the 2008 crash, the average per capita income is around $50,000 per person, still the highest in the world in a large economy. There is no overall shortage of goods and services to go around. There is no deathly squeeze on food supplies, water, energy, or health care systems. There is a continued outpouring of new products.

Our challenges lie not so much in our productivity, technology, or natural resources but in our ability to cooperate on an honest basis. Can we make the political system work to solve a growing list of problems? Can we take our attention away from short-run desires long enough to focus on the future? Will the super-rich finally own up to their responsibilities to the rest of society? These are questions about our attitudes, emotions, and openness to collective actions more than about the death of productivity or the depletion of resources.

In the following chapters, we will retrace our steps as a nation. How did the world’s leading economy reach such a position of despair, and apparently in such a short period of time? We will diagnose America’s ills by studying four dimensions of the American crisis: economic (

chapters 3

and

6

), political (

chapters 4

and

7

), social

(

chapter 5

), and psychological (

chapter 8

). By taking the economic, political, social, and psychological facets together, we can piece together an understanding of how America went from decades of consensus and high achievement to an era of deep division and growing crisis. That story will enable us to look forward toward solutions.

CHAPTER 3.

The Free-Market Fallacy

After decades of global economic leadership, America began in the 1980s to forget the basic lessons of economics, parroting slogans (typically about the wonders of the free market) while neglecting the art of economic policy. One of the most basic and important ideas of economics—that business and government have complementary roles as part of a “mixed economy”—has been increasingly ignored, to my amazement and consternation. This chapter aims to help make up the lost ground.

In this chapter I discuss the three main aims of an economy—efficiency, fairness, and sustainability—and show that the government must play an active and creative role alongside the private market economy to enable society to achieve them.

The Age of Paul Samuelson

Fortunately for me, I was well educated in the merits of the mixed economy during my student years (1972–1980), by intellectual giants who had done much to guide America’s economy after World War II. The era of economic thought from the 1940s to the 1970s can be called the Age of Paul Samuelson, the economic genius at

MIT who personified the economics profession during the heyday of America’s global leadership. More than any other economist of his time, Samuelson provided the intellectual underpinnings of the modern mixed economy created in the United States and Europe after the Second World War.

As a freshman at Harvard College, I studied from Samuelson’s famed introductory textbook and his

Newsweek

columns, began a lifetime of reading his seemingly endless series of pathbreaking papers, heard wonderful stories about his scintillating intellect, and was able to attend his lectures or watch him in action at economics conferences. He was the undisputed doyen of American economic science and the first American winner of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. He was also unfailingly kind and supportive to me as an aspiring young economist, as he was to generations of students.

His lifetime of remarkable scholarly output both established and epitomized five core ideas of modern mixed capitalism, which my fellow students and I imbibed in our introduction to economics:

- Markets are reasonably efficient institutions for allocating society’s scarce economic resources and lead to high productivity and average living standards.

- Efficiency, however, does not guarantee fairness (or “justice”) in the allocation of incomes.

- Fairness requires the government to redistribute income among the citizenry, especially from the richest members of the society to the poorest and most vulnerable members.

- Markets systematically underprovide certain “public goods,” such as infrastructure, environmental regulation, education, and scientific research, whose adequate supply depends on the government.

- The market economy is prone to financial instability, which can be alleviated through active government policies, including financial regulation and well-directed monetary and fiscal policies.

Samuelson’s great synthesis called on market forces to allocate most goods in the economy, while calling on governments to perform three essential tasks: redistributing income to protect the poor and the unlucky; providing public goods such as infrastructure and scientific research; and stabilizing the macroeconomy. This approach appealed enormously to me as a young student of economics and helped me understand the complementary responsibilities of the market and the government. I found the concept of the mixed economy to be compelling, and I still do after forty years.

The ideas of Samuelson and his great contemporaries, including Nobel Laureates James Tobin, Robert Solow, and Kenneth Arrow, did not arise from pure theorizing. Many aspects of the mixed economy were put into place during the New Deal, World War II, and the early postwar period. Pure theory helped those great economists account for what they observed in the economy, and their ideas, in turn, shaped further economic policies. Ideas and history thereby interacted in a dialectical process. Pivotal historical experiences such as the Great Depression and World War II guide economic theory, while economic theory helps to shape the next steps of history. This is the great drama and thrill of economics: with a deeper understanding of events comes the chance to help the world on its historic arc toward greater well-being.

Intellectual Upheaval in the 1970s

Little did I realize in my student days that a huge intellectual storm was about to hit the field of economics: the consensus over the mixed economy was about to be jolted. In 1971, the year before I entered college, the Bretton Woods dollar-exchange system collapsed, basically because America’s inflationary monetary and budget policies during the Vietnam War era were destabilizing the world economy. The United States abandoned its monetary links with gold on August 15, 1971. Inflation soared worldwide as the major market economies

searched for a new approach to the global monetary system. The situation was further complicated when the oil-exporting countries sharply raised oil prices in the midst of the global inflation. The surge of oil prices during 1973–1974 led to the combination of economic stagnation and inflation, christened the “Great Stagflation.” The subject of stagflation became a major focus of my own early research.

1

The crisis of the world economy during the 1970s proved to be a decisive break in U.S. economic and political governance. The optimism concerning the mixed economy was assailed. Within academia Samuelson’s synthesis of market and government was under heated attack. Economics as an academic discipline was turned on its head by the ascendancy of a new school of thought led by Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, one that deemphasized the mixed economy and played up the functioning of the market system. Though Friedman and Hayek were definitely not free-market zealots, as they supported a clear but limited role of government, they also expressed greatly increased skepticism about the role of government in the economy.

My preparatory economics education ended in 1980 with my PhD. I had entered Harvard as a freshman in 1972 during the Age of Paul Samuelson and joined the Harvard faculty as an assistant professor in the fall of 1980 at the start of the Age of Milton Friedman. That year, Ronald Reagan won the presidency on a platform of rolling back the role of government. Across the Atlantic, the United Kingdom’s new prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, stood for the same. Together, Reagan and Thatcher launched a rollback of government the likes of which had not been seen in decades. Many of the measures of the Reagan presidency, notably the sharp cut in the top tax rates and the deregulation of industry, won support throughout the economics profession and the society.

The main effect of the Reagan Revolution, however, was not the specific policies but a new antipathy to the role of government, a new disdain for the poor who depended on government for income support, and a new invitation to the rich to shed their moral responsibilities

to the rest of society. Reagan helped plant the notion that society could benefit most not by insisting on the civic virtue of the wealthy, but by cutting their tax rates and thereby unleashing their entrepreneurial zeal. Whether such entrepreneurial zeal was released is debatable, but there is little doubt that a lot of pent-up greed was released, greed that infected the political system and that still haunts America today.